Then there are the weird ones, like me, who call themselves mathematicians. When we think of maths, we think of shapes, colours, patterns, creativity, freedom, insight and the feeling of making deep connections.

Why is there such a huge gap between how mathematicians and the general population see and experience maths?

The myth of the maths gift

So many people give up on engaging with maths from a young age, deciding, “I am just not a maths person, I’m not good at maths.”

There is a deeply entrenched view in our society that ability to learn and master mathematical understanding comes from an inborn gift rather than from hard work and perseverance.

When we hold this view from a young age, the maths classroom becomes a place where we are constantly being judged not good enough, a place of repeated failure and shame.

And with each failed test, with each time we’re put on the spot to answer a question we’re not prepared for, we think, “See, I’m really not a maths person. Get me out of here, I don’t belong.”

Then grows maths anxiety.

The work of academics like Carol Dweck and Jo Boaler of Stanford University suggests that the strongest predictor of achievement in maths is mindset—specifically, whether you believe you can grow your maths ability or whether it is fixed.

Come again? You’re saying I just have to believe I’m good at maths and then I can be?

Not quite.

You just have to believe you can be better and then you can. Working at maths over a long period of time with this belief, you will see significant improvement. Remember The Little Engine That Could? Belief and effort get you over the hill, in maths, just like everything else.

The strongest predictor of achievement in maths is mindset—specifically, whether you believe you can grow your maths ability or whether it is fixed.

Students with a fixed mindset create a self-fulfilling prophecy. Because they believe they have no ability at math class, when they encounter a problem or something they don’t know, they give up easily.

Students with a growth mindset will try again and again and again, use different strategies and find help from different sources.

An analysis of achievement against mindset of the 2016 international maths test, PISA, showed a gap in achievement equivalent to a year and a half between students with a fixed mindset and students with a growth mindset.

A lack of connection

So OK, you say, if I change my belief around maths and “I think I can, I think I can”, I can learn a lot more. But why would I want to? That still doesn’t stop maths being boring and irrelevant, right?

Now here is perhaps a bigger problem.

I just asked my housemate what the second most read book in the world was.

When I told her it’s Euclid’s The Elements, she said, “How? I’ve never even heard of it!”

This is precisely the response I’d expect if I randomly asked someone on the street.

It’s the initial treatise on the basics of geometry, with revolutionary facts like the shortest distance between two points is a straight line and parallel lines never meet.

The rigour of reasoning and proof was unmatched until the 19th century—it is a masterpiece of reasoning and logical thought.

The world we now live in is literally built on the works like this and the works of Descartes, Pythagoras and Newton. (Hey, you know the guy who had an apple fall on his head? Turns out he also casually invented calculus in order to have a means to figure out the mass of the Earth.)

Professor Edward Frenkel makes the argument that mathematicians have done a bad job of promoting themselves. The masterpieces of art and literature and even science (think da Vinci, Shakespeare, Einstein) are very different. Even if we haven’t seen them directly or read them, we know them as a fundamental part of our culture, and we know their beauty.

As mathematicians, we haven’t shared this beauty of the masterpieces in a way that has allowed the general population to appreciate them.

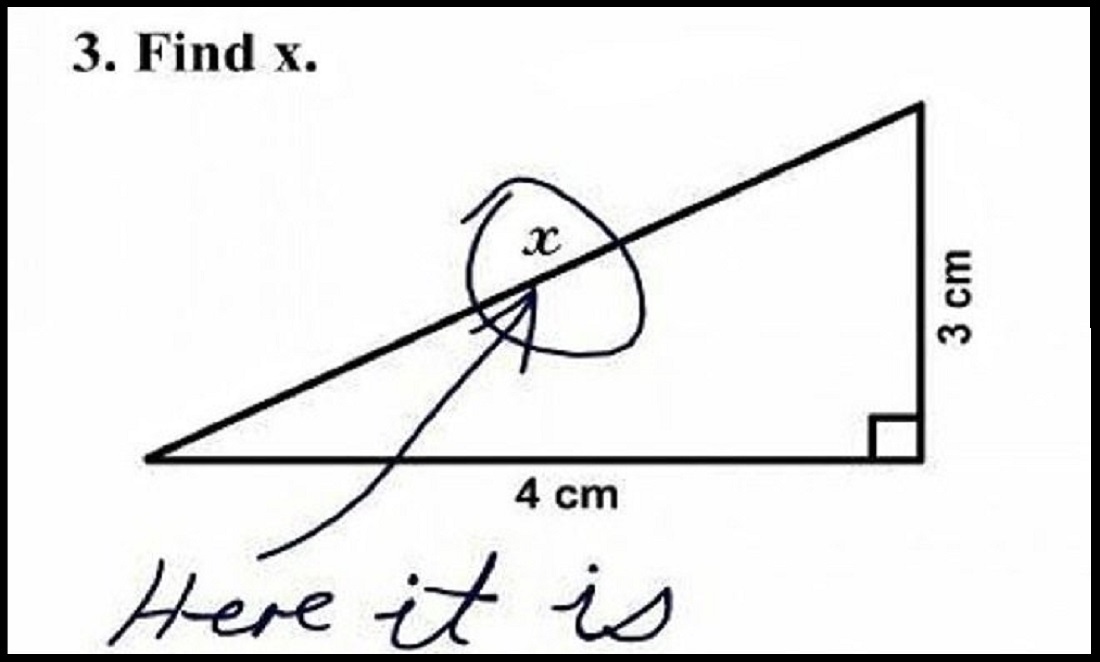

But more of a travesty than this is the way traditional education has presented maths as a set of disconnected procedures: add these two numbers, multiply the base by the height, find x …

This bores me.

I taught maths as a high school teacher and had to teach like this. My students were bored too.

There are two big things missing: connection of ideas and connection to the real world.

To present maths in a way that isn’t horribly boring, you actually only need one of these two (but both together is great as well).

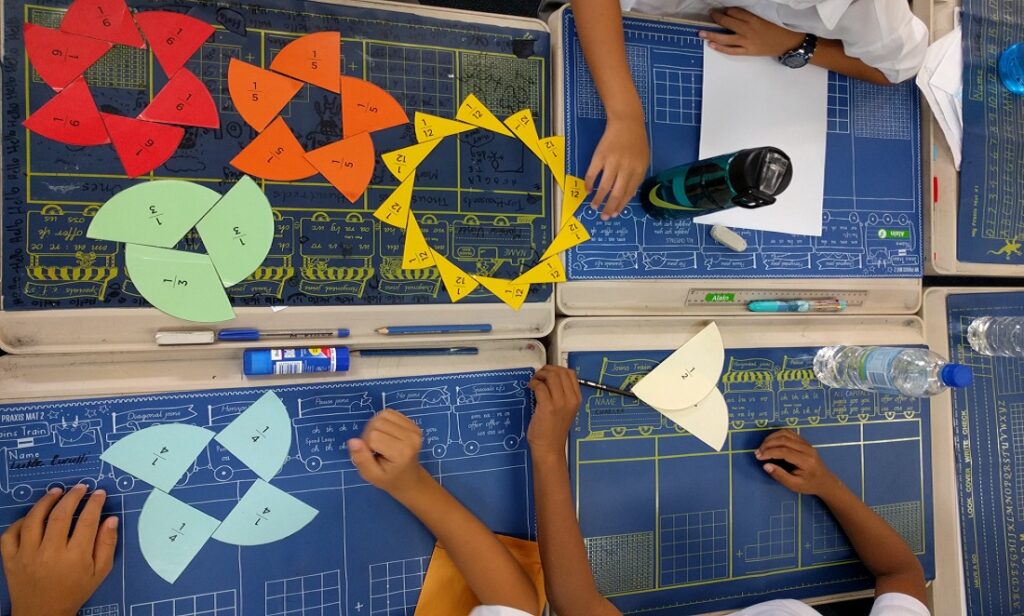

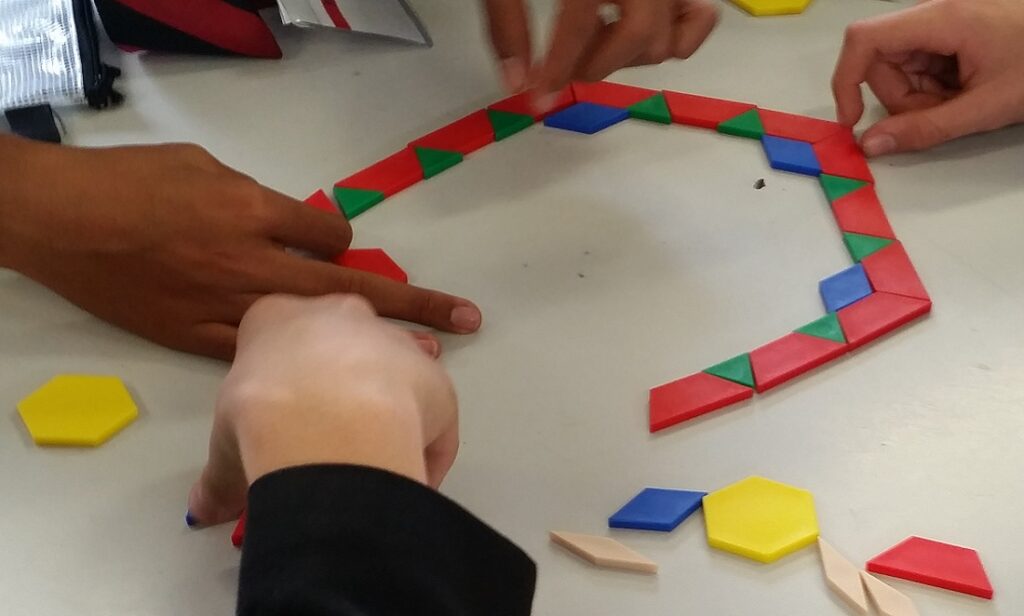

I’ve been doing something different lately in my work with Scitech as a professional learning consultant: inquiry maths. I go into classes and bring coloured geometrical shapes, rods and fraction circles, and I set focused tasks of exploration.

Students play, seek out patterns, ask their own questions, discuss and debate their ideas.

I used to ask a class of 30 students who liked maths, and two students would put their hand up.

I’ve taken this approach into more than 60 classrooms and consistently seen a whole classroom engaged and excited about mathematical ideas.

People enjoy connecting ideas.

In an example of real-world maths, I recently set a task for a couple of hundred students to figure out how much area it would take to power the whole of WA in solar power. They worked in small groups, fully self-motivated to tackle the problem for an hour.

People enjoy tackling big problems that connect to the real world.

The good news

The things I’ve been doing are just small-scale examples of great movements in maths education and engagement happening around the world.

Youcubed.org provides courses for teachers, parents and students to rediscover the joy of mathematics. Tens of thousands of people have tried these.

Math for Love, in Seattle, is doing similar work creating an alternative curriculum around problem-solving and investigation. Try the Diffy Squares task for an experience of playful thought-provoking maths anyone can do.

Dan Meyer teaches maths using videos of real-world scenarios in his 3-Acts maths lessons.

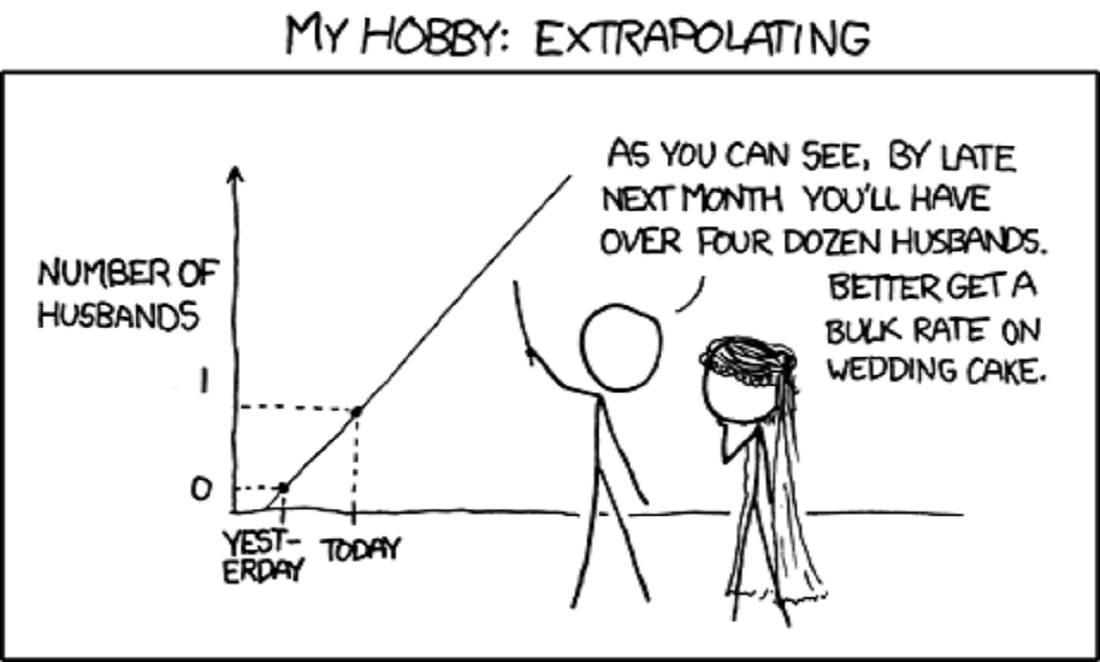

The public profile of maths is lifting as well through the works of YouTube channels like Numberphile and Veritasium, websites like the popular comic xkcd and the growing profession of the maths communicator (check out Hannah Fry below or Vi Hart) and even the maths comedian (check out Matt Parker or Simon Pampena).

If you’re one of those people who hated maths, just aren’t “a maths person” or think it doesn’t matter, I hope next time you think about maths you remember there’s a whole world of beauty, connection and understanding to tap into if you can just make the effort.