Why don’t humans live underground like the hobbits from The Lord of the Rings, or the people from the vaults in Fallout? Why don’t our skyscrapers dig as far into the ground as they do into the sky?

It’s a complicated question, and to understand the answer, we’re going to need to dig a little deeper.

Science says …

We humans have evolved to live on the surface. We’re not like a beetle that’s adapted to burrow or an eel that’s adapted to swim. We need a solid surface for our feet, and air to push our bodies through.

Not every species is cut out for life underground.

So if we want to live underground, the first thing we have to do is bring the air and the solid surface with us.

But breathing and moving around is just what we need to exist underground. To live, most research says we need a little bit more.

People don’t just want natural light, fresh air and views. An increasing amount of research suggests that we need them. A lack of natural light is linked to the aptly named Seasonal Affective Disorder, or SAD, while access to green, open spaces do wonders for our mental and physical health.

So if we want a happy and healthy life underground, we would need to bring these things with us too.

Technological Troglodytes

Going underground might not be ideal for humans – but for our stuff, which doesn’t care so much about air and light, it’s pretty ideal. And in a lot of cases, this is an excellent choice, because it means we have more of that precious above-ground space for humans. That’s why we have underground freeways and power lines instead of underground houses.

But there are some other weirder reasons to move things underground.

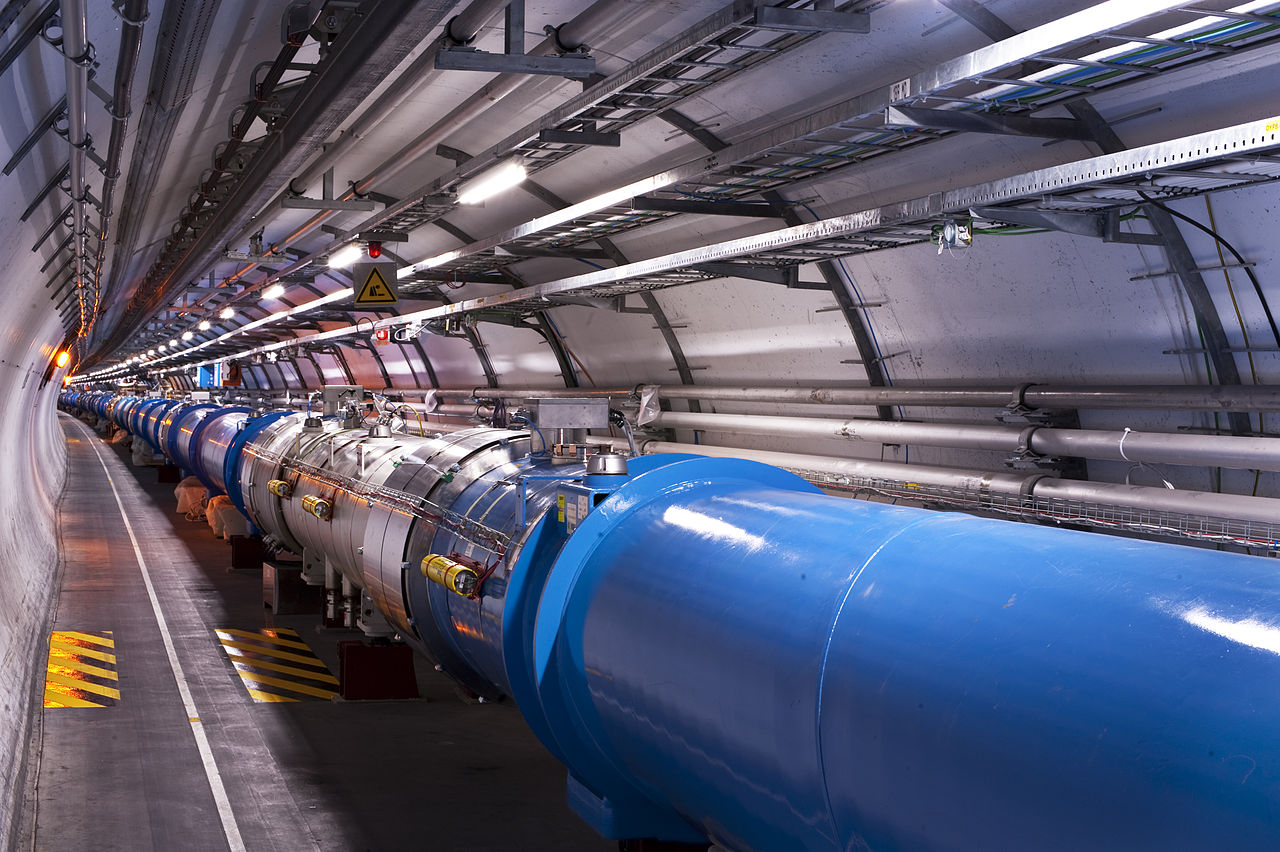

All that dirt, for example, is great at stopping radiation. Atoms are mostly empty space, so if you’ve only got a thin layer of stuff, like a brick wall, many types of radiation can whizz right through. The more stuff you have between you and the radiation, the the more likely it is to hit that stuff before it hits you. So, if you’re building a fallout shelter, a super-sensitive physics experiment, or a place to store nuclear waste, digging down underground will save you a lot of time.

Being surrounded by all that mass is good for other things as well. It can help dampen vibrations, which is useful if you’ve got a very sensitive microscope. It can also help stabilise temperatures, which is great if you’re building a data centre or a giant refrigerated seed vault.

But like always, there’s a limit, even for the stuff that does work underground – because working underground is harder than it looks.

The effort of engineering

To build above ground, there’s really only one force you’ve got to deal with: gravity. Your above ground house has to contend with a little wind every now and then, but most of the time it just has to support its own weight.

Move underground, and all that changes. Unlike in Minecraft, real dirt doesn’t stay up on its own. So as well as supporting its own weight, your whole building has to act like a giant retaining wall, pushing back the dirt all around it.

If you dig deep enough that you get into rock instead of dirt, you’re facing a different set of problems. Rocks are much harder to remove than dirt (there’s a reason we pour concrete as a liquid) – and even though rock seems structurally stronger, there’s still no guarantee that it’ll stay up on its own.

And that’s before we get into all the other things that lie underground. There’s water to watch out for, roots to remove, pipes to pick around, and artefacts to archive. When we build up, we build into empty air – but when you’re building down, you can never be quite sure what surprises are in store for you.

And after all that, you still need somewhere to take all of that heavy dirt, so you can start building in your hole. You’ve basically spent a lot of time and effort to make some empty space – which you could have had for free just by building at the surface.

Mined the maths

So if it makes so little sense to live underground, how come some people actually do it?

It all comes down to maths – quite often, the maths of economics. Most of the time, going underground isn’t worth it. Sometimes, it is. Wherever people live underground, you’ll probably find something unusual tipping that equation.

In the South Australian town of Coober Pedy, it’s extremely hot above the ground. So building underground keeps things nice and cool. In fact, many of their underground buildings started off as opal mines, so the hard engineering was already done.

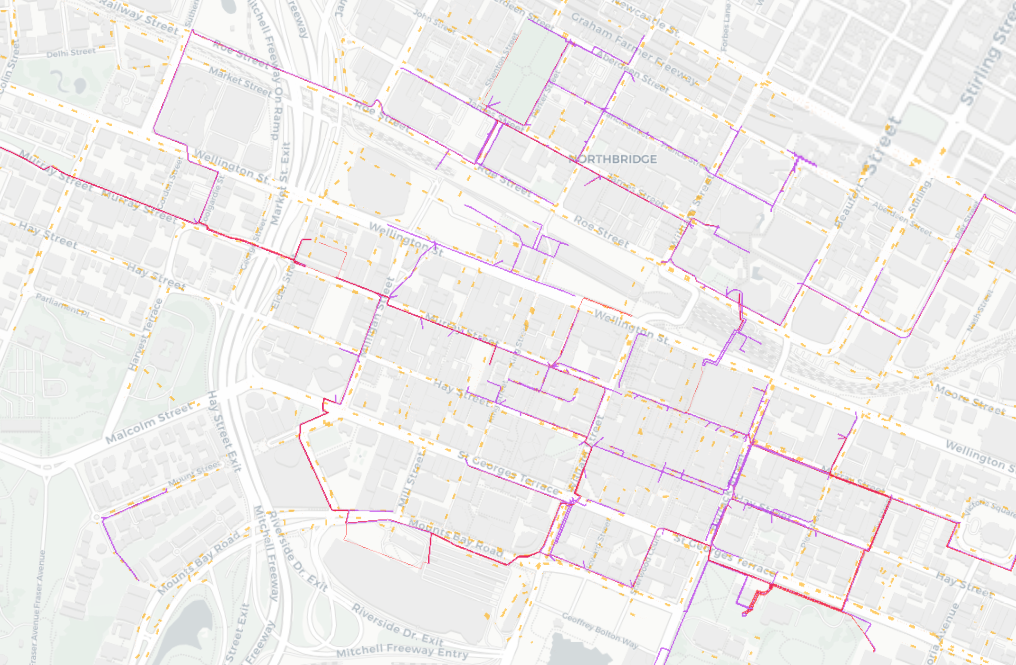

In the south-west of WA, there’s a custom-built ultra-low impact home that uses the ground to provide thermal insulation – but they also spent a lot of time and effort to make sure they had air and light.

In a city as big as Beijing, the empty space above ground is pretty much full. And because location is just that important, over a million people are estimated to be living in bunkers and basements.

And if we ever start living somewhere other than Earth, where the great outdoors isn’t quite as nice, a stable temperature and protection from radiation starts to look pretty appealing.

But for most of us on this planet, building above ground is cheaper, easier and just plain nicer. And unless we all move to the Moon, that’s probably the way it will stay.