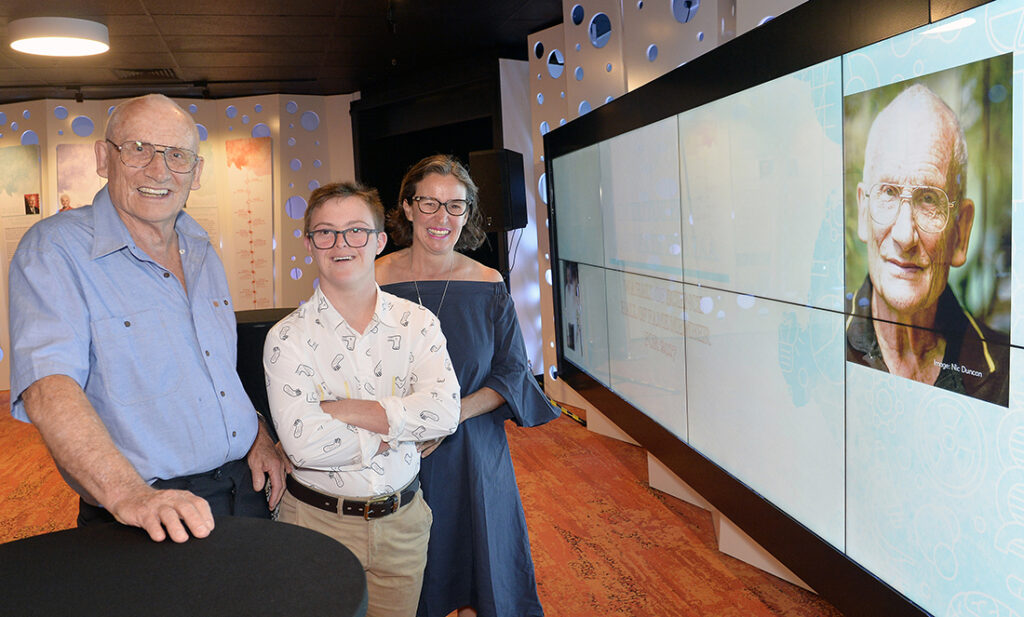

On 23 November 2017, Professor John Pate was officially inducted into the WA Science Hall of Fame at Scitech.

The honour recognised his outstanding contributions to plant science and dedication to teaching.

But like the plants he studied, there’s even more to John beneath the surface.

I had the privilege of chatting with John following his induction—and the challenge of trying to encapsulate his immense, full and fun life in just one short story.

The professor and the pea

John’s amazing career had humble beginnings—starting in a pea patch!

Growing up in the UK during the Second World War, there was a national food shortage. Families were encouraged to grow their own food, so that’s exactly what John’s family did.

While helping his father grow peas and beans (two types of legumes), John learned these plants had their own special power.

On the roots of the plants were nodules—little pockets full of bacteria that helped the plants feed off nitrogen in the air. A handy little skill, given there was no nitrogen fertiliser during the war to help plants grow.

“These plants are therefore independent of having to give them nitrogen fertiliser,” John explained.

“They live off the nitrogen from the atmosphere, and that really blew me away.”

It was this realisation that inspired John’s future research.

The main thrust of his work was figuring out how much nitrogen legumes produced—and how much of that nitrogen was transferred to the next planted crop.

After legumes are harvested, their roots are left behind. They decompose, releasing nitrogen in the soil for the next season’s crop.

“Nitrogen fertilisers are very expensive, and if the farmer can get some of his nitrogen free from the legume nitrogen fixation, of course he would be delighted.”

Tough as old roots

John’s contributions to agriculture are only a portion of his overall achievements. When he made the move to WA, he became fascinated with the unique flora, specifically, the native plants’ resilience to extreme climate events. Our winters are cold and wet while our summers are hot and dry.

“I wanted to know how they were able to survive under those conditions,” he said.

He was especially interested in how the roots helped plants survive in difficult conditions. He managed to find all sorts of interesting adaptations.

He found plants with special long-lived hairs on their roots that bind sand and thus kept them from drying out in summer. And other plants with roots that grew many metres down to get water when the top of the soil had dried.

This work, along with other evaluations John conducted, greatly informed knowledge of WA’s unique native flora.

The dizzying highs

When reflecting on the high points of his career, John’s thoughts turn to the students he lectured and mentored over time.

“Teaching was always my penchant … that’s what I really loved,” he said.

John always kept his lessons entertaining. He was never afraid to crack jokes in class—a trait he attributes to his “Irish upbringing”.

“The best highlight for me was where one or other of my research students would come back 10 years after gaining a PhD and give us a seminar, and they would say things that I didn’t even understand.”

It’s a credit to the supportive teacher John was. He wasn’t afraid to be outdone by the next generation—in fact, he was delighted.

“I was very pleased because they’d outstripped anything that I could do, and they’d proved that the training that I’d given them allowed them to jump off into the unknown,” he smiled.

The lowest lows

John’s self-professed “lowest point” occurred while he was chaperoning a school reunion event at UWA.

He was watching the fun from the sidelines, blending in with the furniture, when suddenly a girl took notice of him.

“She came up and said, ‘Oh, you’re Professor Pate! You taught me at university’,” he told me.

The girl proceeded to gush, remembering the jokes John used to tell in class. He was feeling quite chuffed, until things came to an abrupt halt.

“The disastrous throwaway line was, ‘What was it you taught? Chemistry or something?’,” he laughed.

Getting the last laugh

All jokes aside, John does remember one particularly painful moment from his childhood.

One day, John noticed a rabbit eating its own poo, and like a true budding scientist, he couldn’t wait to tell the rest of his classmates.

Unfortunately, the show-and-tell did not go over well.

“The girls wouldn’t talk to me afterwards, which didn’t matter, but the boys … ended up spreading the rumour that I ate my own poo!”

Thankfully, his teacher could see his distress and announced to the class, “One of these days, John Pate will discover something very, very important and who will be laughing then?”

Little did she know he would go on to achieve such great things. But humble as always, John says he is “still trying to live up to her expectations”.

And John was pleased to report he did eventually learn the reason for the rabbit’s odd craving.

“They eat it to get more nutrients out of it the second time around.”

A born scientist

John hasn’t let his retirement slow down his scientific discoveries.

He’s enjoying his golden years fulfilling one of his passions that he never got to chase fully in his career—studying animal behaviour.

He observes the birds, foxes, reptiles and, yes, even rabbits, from his picturesque Denmark property.

“Good observations combined with curiosity, like having to see the rabbit eating its own poo, are very often the basis of good science,” he said.

He and two close colleagues are even writing a book called Unravelling the secret life of roots. He jokingly refers to it as a “swan song”.

“It won’t be a best seller,” he laughed, “but it’s a very interesting story because most people just look at the flowers and the above parts of plants, but we want to really make our mark by saying things that go on under the ground are also important.”

As John continues to shed light on the world’s mysteries, he feels grateful just to be a part of it all.

“After all, we were just reaching out into the unknown. Science is like an ever-expanding horizon. What you’ve found last month is likely to be superseded by something else,” he said.

“That’s one of the beauties of science, you never see far, there’s always new challenges in front of you. So this is such an exciting thing.”

“We were just reaching out into the unknown. Science is like an ever-expanding horizon.”

What is the secret to a full life?

How can you talk to a man of such great accomplishment and not ask this fundamental question?

John believes it’s as easy as working hard but never taking yourself too seriously.

“Some of my colleagues were very interested in their reputations and whether other people would like what they’d done,” he said.

“As far as I was concerned, I just explored things [and] got excitement out of discovering things, regardless of whether others would be interested.”

John also talked of the importance of hard work, coupled with a good work/life balance. During the week, he’d work hard at his job, but on the weekend, he’d put all the science aside for quality time with his family.

At the root of John’s achievements in science, his Christian faith and his beautiful outlook on life, there is one strong underlying sentiment.

“To my mind, it’s all a wonderful puzzle, with so much unfathomable majesty and mystery behind it.”