Inside a dimly lit laboratory, strangely coloured chemicals bubble in vials. Thunder rumbles overhead as a scientist circles a table. The shape of a human body lies beneath a white sheet.

The scientist wears a lab coat, thick rubber gloves and a pair of welding goggles. They let out a load cackle as they flip a switch. A bolt of lightning strikes a metal rod on the lab’s roof, carrying a powerful bolt of electricity to the table. The body begins to rise … IT’S ALIVE!

The good, the mad and the ugly

Contrary to movies like Frankenstein, the vast majority of scientists aren’t mad. Becoming a successful scientist takes decades of learning. They also need to abide by a strict set of moral codes.

But there are past scientific practices that seem horrible to us now. If scientists are so moral and reasonable, how can this happen?

“Scientists are deeply immersed in the societies they happen to be located in. They absorb those values,” says Professor Rob Wilson.

“Some of the real eyesores through history are cases where people thought they were being very morally progressive in accord with the values of the time.”

Rob’s a professor of philosophy at UWA. He wrote The Eugenic Mind Project, which explores the link between past and modern eugenics.

“Eugenics is a good example of that,” Rob says. “A lot of the most progressive left people were very proud of it. They thought that needing to segregate and sterilise people, even coercively, was required.”

The scary real-life science of sterilisation

It’s a little-known fact that Australia was set to sterilise large swathes of its population.

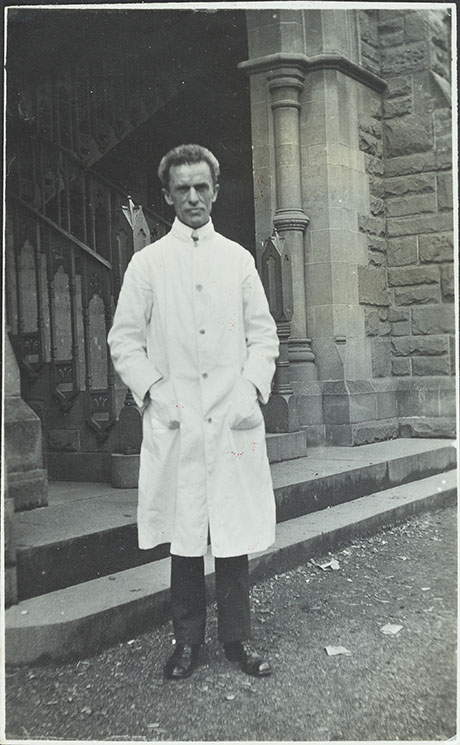

In the early 20th century, Melbourne University Professor of Anatomy Richard Berry and his colleagues, including Premier Stanley Argyle, helped get three Mental Deficiency Bills into Parliament.

According to historian Ross L Jones, “the bill aimed to institutionalise and potentially sterilise a significant proportion of the population – those seen as inefficient”.

“Included in the group were slum dwellers, homosexuals, prostitutes and alcoholics, as well as those with small heads and with low IQs. The Aboriginal population was also seen to fall within this group.”

Pretty abhorrent stuff, right? But it was considered forward-thinking at the time. While the first two Bills failed, the third was passed.

Thankfully, the horrors of World War II made eugenics unpopular, otherwise Australia may well have imprisoned and sterilised thousands of innocent people in an effort to ‘improve’ humanity.

Institutionally ‘insane’

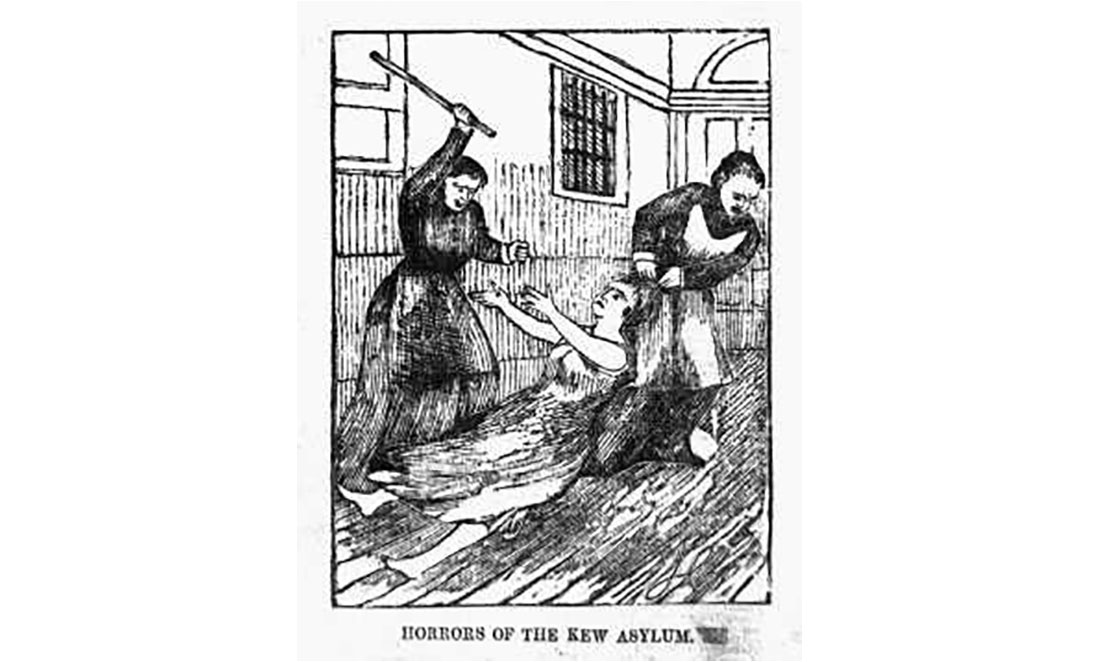

Back in the 1930s, if you were considered ‘undesirable’, you may have been admitted to Kew Lunatic Asylum.

Massively overcrowded, Inspector-General W. E. Jones described patients “herded like cattle” and left undiagnosed for years. This often led to death without proper treatment.

Abuse by staff was common. Patients were beaten in the stomach for refusing to take medicine. If you were lucky enough to be released, often after years of imprisonment, it’s quite likely you would be sterilised and unable to have a family.

It sounds unbelievable, but Professor Berry was a prominent scientist at the time.

His legacy was so great that, until 2017, the University of Melbourne’s anatomy building was named in his honour.

By all accounts, he was a loving husband and caring father to his two daughters. A happy family isn’t the hallmark of a mad scientist, yet Richard Berry advocated for preventing hundreds of people from having their own families. Why?

The ethics of science

Dr Tim Dean is a philosopher, award-winning writer and teacher who specialises in ethics, critical thinking and the philosophy of science.

He says most scientists operate within an ethical framework that includes their personal sense of right and wrong and is informed by their culture, upbringing and conscience.

“But also, science has a very strong ethics component. To do a particular study, you need to get ethics approval, there are norms around how papers are published and distributed, how information is used, how it’s shared – these are all informed by a kind of a professional body view of ethics around scientific ethics,” says Tim.

But problematic science doesn’t just live in the distant past. In 2018, Southern University of Science and Technology biophysicist He Jiankui announced the birth of twins who had their DNA edited to attempt to give genetic resistance to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). He did this without the consent of the parents and against all ethical procedures.

To He, the thought of protecting the world from HIV outweighed the risks of harming the baby girls.

Tim describes this concept as moral licence. It’s a cognitive bias that allows us to justify immoral behaviour while retaining our view of ourselves as moral beings. For example, you might be more likely to cheat or steal if you buy green goods.

“Technology is arguably moving a lot quicker than our ethical deliberation can catch up. Look at social media, the way technology has affected us, and I think a lot of social media has been quite harmful for humanity,” Tim says.

“And the norms and the regulations around it have lagged well behind the technological change. From my perspective, the real threat is that we may not catch up in time to stop the next Manhattan Project.”

Dropping a bombshell

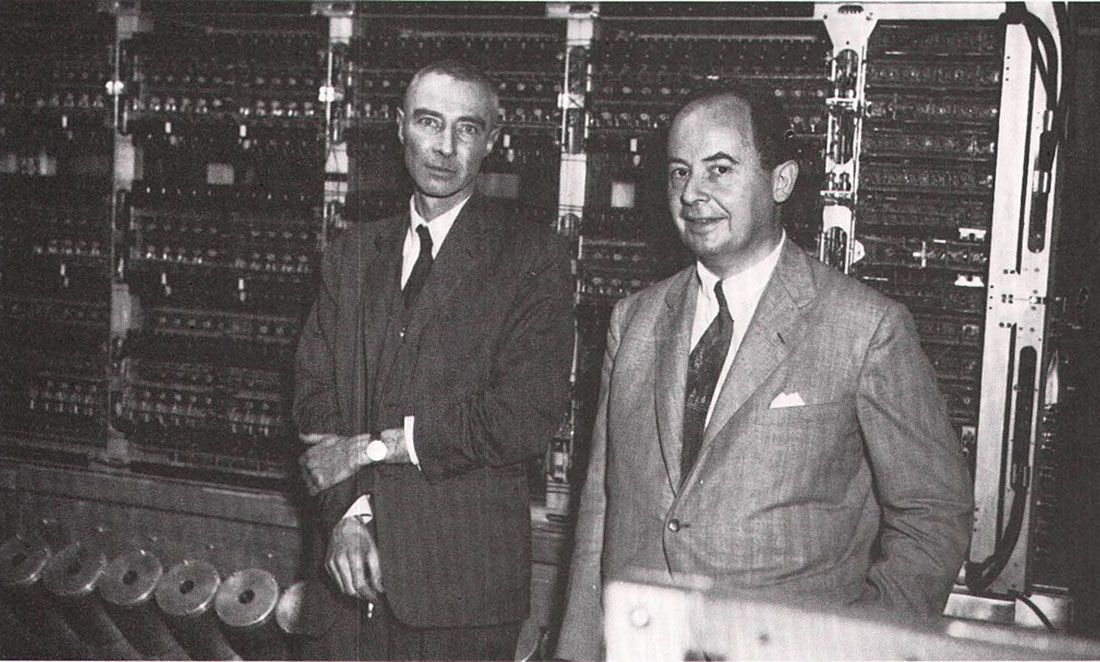

The Manhattan Project is one of history’s most extreme cases of moral licensing.

J. Robert Oppenheimer is known as the father of the atomic bomb. He was a key figure in developing the first nuclear weapons used to bomb two Japanese cities in an effort to end the United States war with Japan.

Within a few months after the bombings, up to 160,000 people died in Hiroshima, while up to 80,000 died in Nagasaki. The bombings led to decades of cancer and birth defects.

But in his farewell speech to the Association of Los Alamos Scientists, Oppenheimer didn’t apologise for inventing the bombs, despite the fatalities and casualties. He said pursuit of an atomic bomb was inevitable and that scientists must “expand man’s understanding and control of nature.”

While the catastrophic effects are undeniable, the scientists working on it believed they were acting in the greater good. This raises the question, how can scientists make sure their discoveries are used for ‘good’ and not ‘evil’?

Taking the moral high ground

In Tim’s new book, How We Became Human and Why We Need to Change, he explores how human cultures have vastly different values depending on their needs. He says there’s unlikely to be one true morality – that evil is not an objective phenomenon.

There’s no ‘badness’ particle we can break down with a Hadron Collider or view with a microscope. Our moral world is built by constant negotiation of different groups of people with differing values.

These values evolve over time, and even acceptable actions today may be considered monstrous in the future. Tim says technology has caused this changing morality to speed up.

“When you look back at history, it’s almost impossible to anticipate how morals will change over the course of 50 or 100 years,” he says.

“But one pattern is the acceleration of moral change. For most of human history, the moral norms you were born into were there when you died. Now, things from 10–20 years ago are not permissible.”

Rob has an idea about how to ensure we’re acting ‘good’. “It’s possible within a particular cultural context,” he says, “if you compare your values to other cultures and the historical trajectory.”

Because our reasoning tools are inherited from our culture, the moral faults of our era are largely invisible to those tools.

Rob says morality in science (and people in general) comes from listening to the perspectives of others outside our own bubble – including our enemies.

We don’t have to agree with them, but we may be able to avoid our worst faults by understanding them. While it might not be a cure-all for the mistakes of the age, it could help save us from our worst follies.