Everyone knows the classic elements of a Disney movie. A hero with their sidekick (usually some kind of sassy, adorable animal), some catchy tunes and a little bit of magic. But could there be science hidden among the show tunes and pixie dust?

Of course! Science is everywhere you look. Take a look at some of the science Disney got right.

Moana wayfinding

The thing that always blows me away about astronomy is how the earliest humans were able to use it in ingenious ways.

The ancient Polynesian peoples colonised much of the Pacific Ocean using the skies as their guide. Their advanced knowledge and observation of the night sky allowed them to navigate across thousands of miles of open ocean.

They used a process called celestial navigation. They mapped the skies and identified where certain stars rise and set. This became their compass, directing them the right way to go.

Then to hold the course, they’d use hand calibration, which brings me to Moana. In Moana, the titular character feels drawn to the sea, but living on an island her whole life, she doesn’t know how to navigate the seas.

Maui teaches her the ways of wayfinding. In particular, he teaches Moana to calibrate by hand. This is a technique with interesting science behind it.

You can calculate latitude by measuring the angles of stars above the horizon. You use your hand like a natural protractor to determine angles in the sky.

At arm’s length, with one eye closed, the width of your pinkie finger equals roughly 1 degree. Your three middle fingers together is approximately 5 degrees, and a fist is 10 degrees. When you stretch out your hand and face your palm outwards, the distance between the tips of your thumb and little finger is 15 degrees.

This is the gesture we see Moana use. With her thumb touching the horizon, she can measure the angle to a specific star to work out her location. Why don’t you try it out yourself tonight?

Frozen from loneliness

Elsa might be every little girl’s hero, but in the kingdom of Arendelle, she was a bit of an outcast. Burdened with icy powers, she spent her days alone, shut away in her room.

Who can forget that iconic scene of the snow filling Elsa’s room when she hears of her parent’s sad fate? With her parents gone, Elsa lost the only people in the world she ever spoke to. It must have felt very lonely. And did you know loneliness can actually make you feel cold?

Some interesting research from the University of Toronto showed the link between coldness and loneliness may be more than a metaphor.

The researchers asked one group of participants to recall a personal experience where they’d felt socially excluded. The other group was asked to remember a time they felt socially included.

They then asked the participants to estimate the room’s temperature. They claimed this information was important for the building maintenance staff. The group who recalled a socially isolating experience reported lower temperatures. Their memories of rejection had made them perceive the ambient temperature as colder.

They tested the theory further by asking participants to play a simulated ball-throwing game. The game was designed so certain players would be thrown the ball a lot, while others were left out.

They then asked everyone who played the game to rate a list of food products in terms of desirability. Players who were left out during the ball toss game rated hot foods like soup higher than those who were passed the ball many times.

So if friends can’t be found, pour yourself a hot bowl of chicken soup!

The Aristocats genetics

Did you get your hair colour from your Mum or Dad? Or Grandma? Or Great Grandpa? In humans, the genetics for hair colour can get pretty tricky, but it’s a bit simpler for cats.

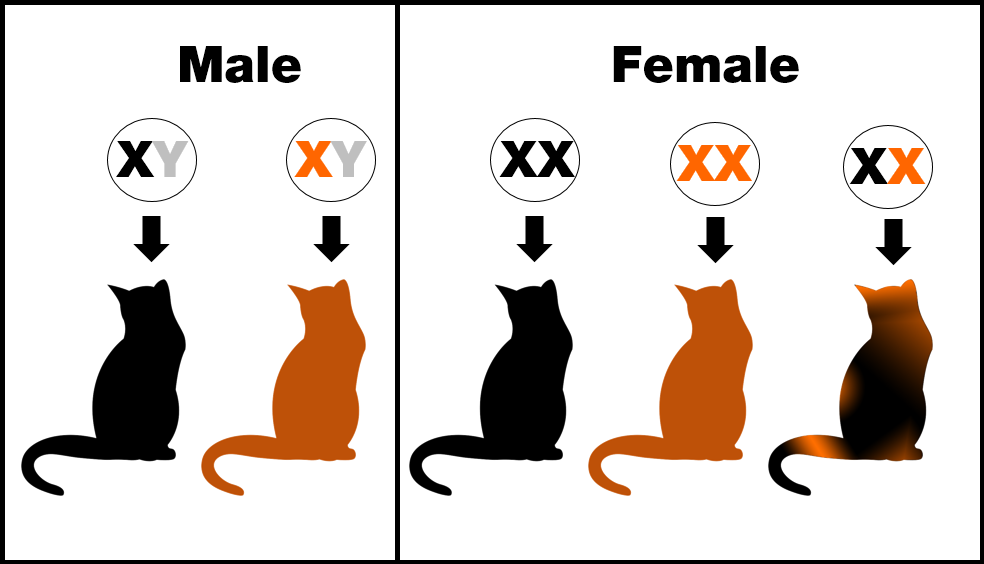

If you’ve ever owned a tortoiseshell cat (a cat with a mix of black and ginger fur), you’ve probably heard that fun fact about how all tortoiseshells are female. This is because the gene that will determine a cat’s fur colour is sex linked on the X chromosome.

Females have two X chromosomes (XX) and boys have one (XY). This means a girl cat could have an X chromosome with a black fur gene and an X chromosome with a ginger gene and express a mix of the two. Since boys only have one X chromosome, they could only be black or ginger. There is also the rare scenario a boy cat inherits two X chromosomes (XXY), in which case it could be tortoiseshell but also likely infertile.

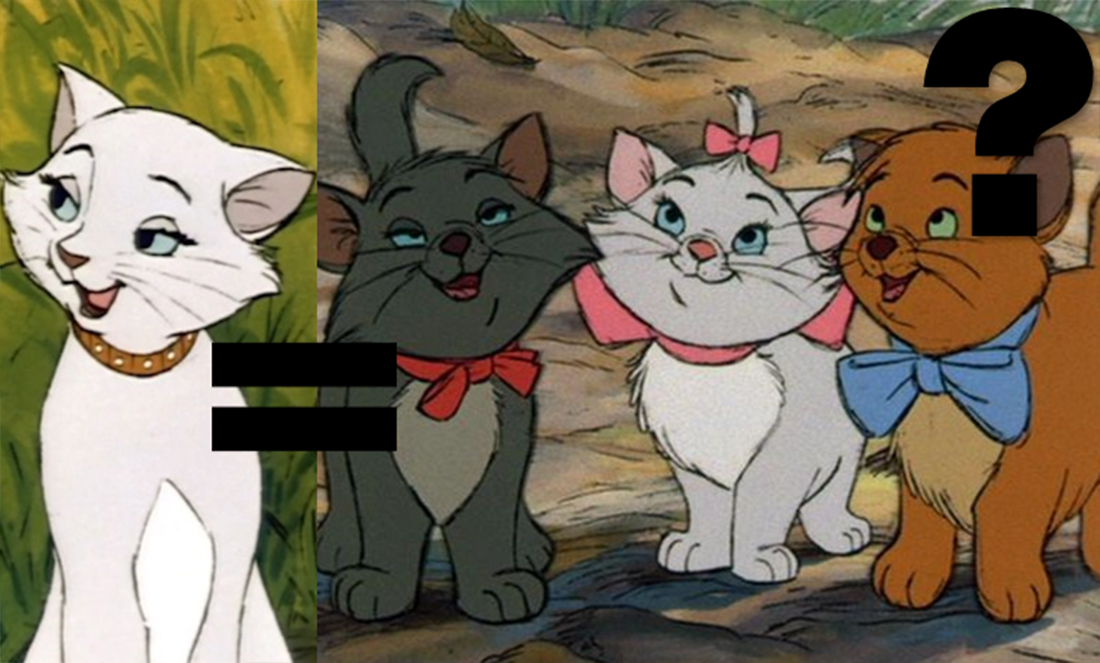

But what does this have to do with the The Aristocats? Duchess—the mother cat—has one female and two male kittens: Marie, Berlioz and Toulouse. All three kittens have different coloured fur. Marie is white, Berlioz is black and Toulouse is ginger. How is it possible to have so many different colours in one litter?

Boys inherit their X chromosome from their Mum and Y from their Dad. That means boy cats can only inherit their fur colour from their Mum. For Duchess to produce one black-furred male kitten and one ginger, she would need to have an X chromosome with the ginger gene and an X chromosome with the black fur gene.

By that logic, Duchess should be a tortoiseshell. So why is her fur white?

Well there’s one more genetic factor at play: the white masking gene. This gene prevents expression of coat colours. It can lead to white spots on a cat or make the cat appear completely white.

So Duchess is a tortoiseshell with the white masking gene, which Marie also inherited. And since the father’s colour would have no effect on any of this, we can stop making assumptions about Duchess swinging with those jazzy scat cats.