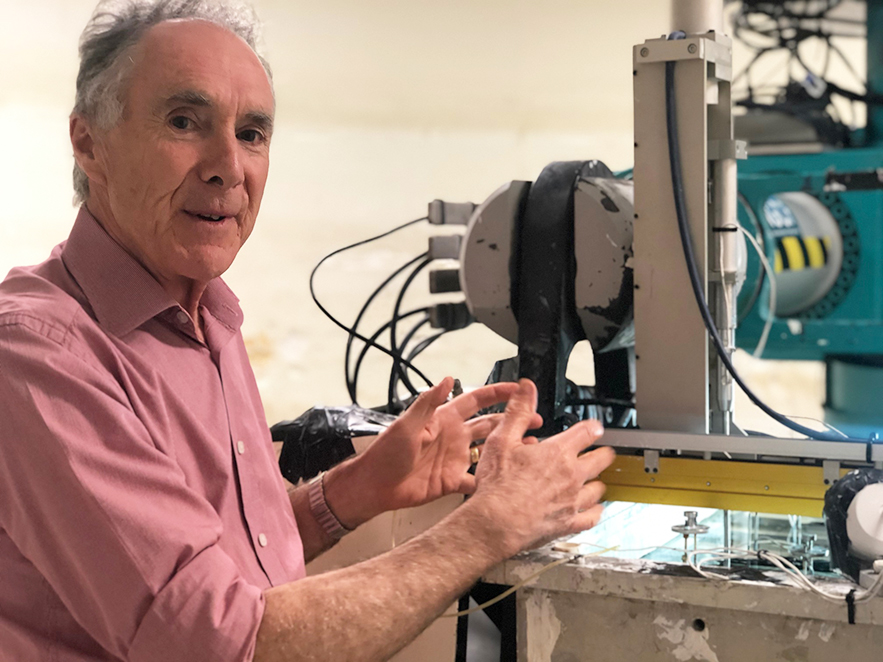

Professor Randolph works across academia and industry to solve complex engineering challenges in skilfully simple ways.

Starting out as a keen mathematician, it was the opportunity for a scholarship from the UK Ministry of Defence that swayed Mark towards engineering instead.

A small moment, but one that kickstarted a distinguished career.

“What drives me is that I do like problem solving and technical challenges. I like new things, new challenges and problems – ones that I feel I can make a contribution to.”

In doing so, Mark has built WA’s international reputation as a hub for excellence in geotechnical engineering, active in a global community looking for new solutions in the field.

But what is geotechnical engineering?

If you haven’t come across it before, this is a branch of civil engineering. It’s all about understanding and characterising the properties of the ground, whether it’s soil or rock, and how it will support and interact with structures.

Mark was drawn to WA because of his specialty in soil and soil structures in offshore environments.

Our seabed sediments are calcareous, which is a nice way of saying ‘made up of calcium carbonate’. Think of sand made from shell fragments, limestone or chalky soil.

This is very different to more conventional sand (‘silica’) and brings with it a whole set of challenges. One of the main problems with calcareous sediment structures is that they’re extremely soft and prone to collapse.

And what do they do?

Like all engineers, it’s about solving problems.

Geotechnical engineers will often work with oceanographers and hydrodynamic specialists to understand the relationship between the sand and the sea.

They then analyse what this means for structures – like pipes or anchoring systems, or columns supporting renewable energy turbines – that are designed for offshore environments.

Mark has gained interest from the oil, gas and renewable energy sectors due to his work in devising new tools and techniques for testing the properties of the offshore soil. And his role in academia ensures these are rigorously researched and modelled to prove success.

The force is strong

This is where it gets very cool, because Mark’s team at the Centre for Offshore Foundation Systems will design a model and test it in their world-leading centrifuge lab.

A centrifuge is a large and powerful piece of equipment that simulates conditions within deep-sea sediments. It does this by spinning at incredible speeds to increase the gravitational forces acting on each grain of soil, and the model structure, as loads are applied. This helps assess how a structure would perform in a real offshore environment.

Measuring 10m in diameter, the largest centrifuge is an impressive fixed-beam beast. It can spin at 150rpm – a tip speed of over 250 km/hr – building to 100G of force for a 2.4-tonne payload. If you know about apparent weight, this is like having a Boeing 787 in the lab.

“When I moved to UWA in 1986, from the start we were determined to build the first centrifuge in the southern hemisphere at the time,” says Mark. “We saw that as vital for growing the research field.”

The Australian Research Council Centre for Offshore Foundation Systems was established in 1997 which helped strengthened the group, who were looking to run tests relevant to what they saw as “a growing offshore industry”.

“It took about four or five years, and our reputation was sufficient for international companies to start asking us to do modelling studies for specific problems. And we did some quite significant ones,” says Mark.

“Since about 2005, we have been known as one of the best concentrations of expertise in this area.”

The combination of numerical analysis and physical modelling means the team’s solution design is accurate and consistent.

This National Geotechnical Centrifuge Facility, led by Professor Conleth O’Loughlin, is now home to 35 PhD students, eight technicians and an onsite geotechnical engineer. They run tests all year round, looking for solutions to local and international projects.

The simple art of solving problems

Mark says he’s happy to pull out the pencil and paper and work out the equations that model a system, but likes to have an obvious endpoint to work towards.

“I see the outcome of any research project as something that needs to be synthesised into a design approach that can be picked up and used directly.”

He clearly relishes the process of tackling a new problem; the challenge of breaking it down into manageable entities.

“You start simple and then build on that. I find that idea continues to drive me now.”

He admits, laughing, that he can get jealous of somebody else who is working on a problem that he didn’t have the opportunity to be involved in.

“Those initial stages of a new problem – it’s fantastic.”

Hall of Fame 2020

Mark is no stranger to receiving awards, and this recent induction into the WA Science Hall of Fame recognises his impressive contribution to STEM fields.

“These awards give you a certain confidence,” he says. “Since being named WA Scientist of the Year [in 2013] I’ve had the confidence to step back and been happy to focus on students, to be there for advice as needed.”

“It’s being able to say, ‘I’ve achieved what I needed to, and now I can step back and have real fun!’. It’s looking at the problems I’d like to contribute to and working on those.”

So what’s next? Seeing renewables accepted as part of the energy mix.

“With my background, I’d like to help when it comes to offshore renewables – to make it economic or to help think through where and what type of initiative to develop. I would like to contribute to that as a final challenge.”