It takes less than a minute for a conversation with artist Tineke Van der Eecken to get from “hello” to “how are we engaging with the Anthropocene?”

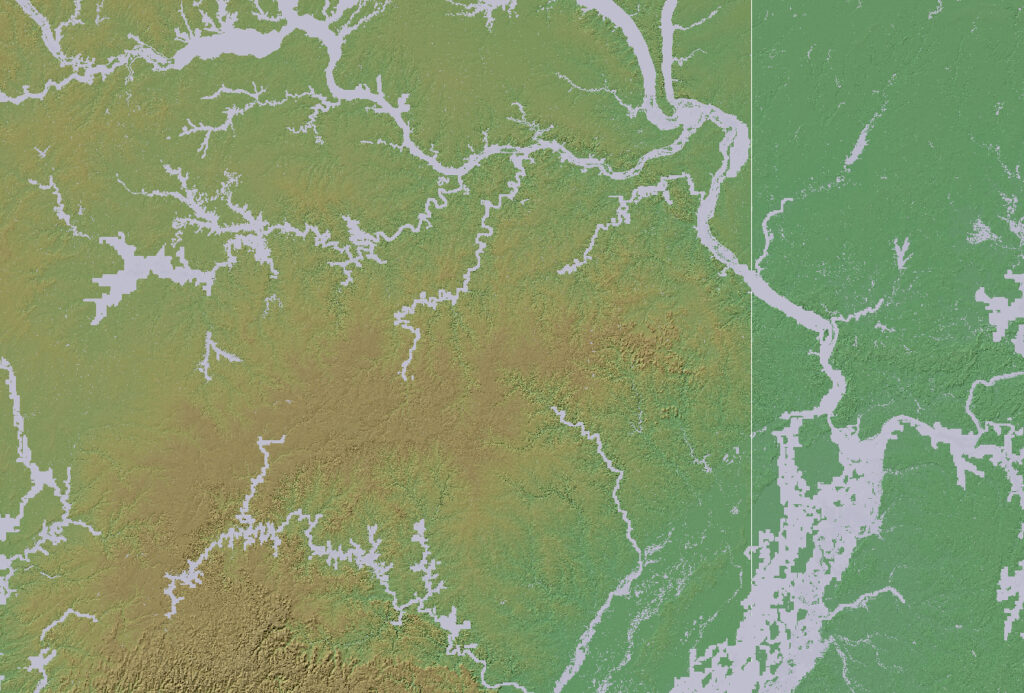

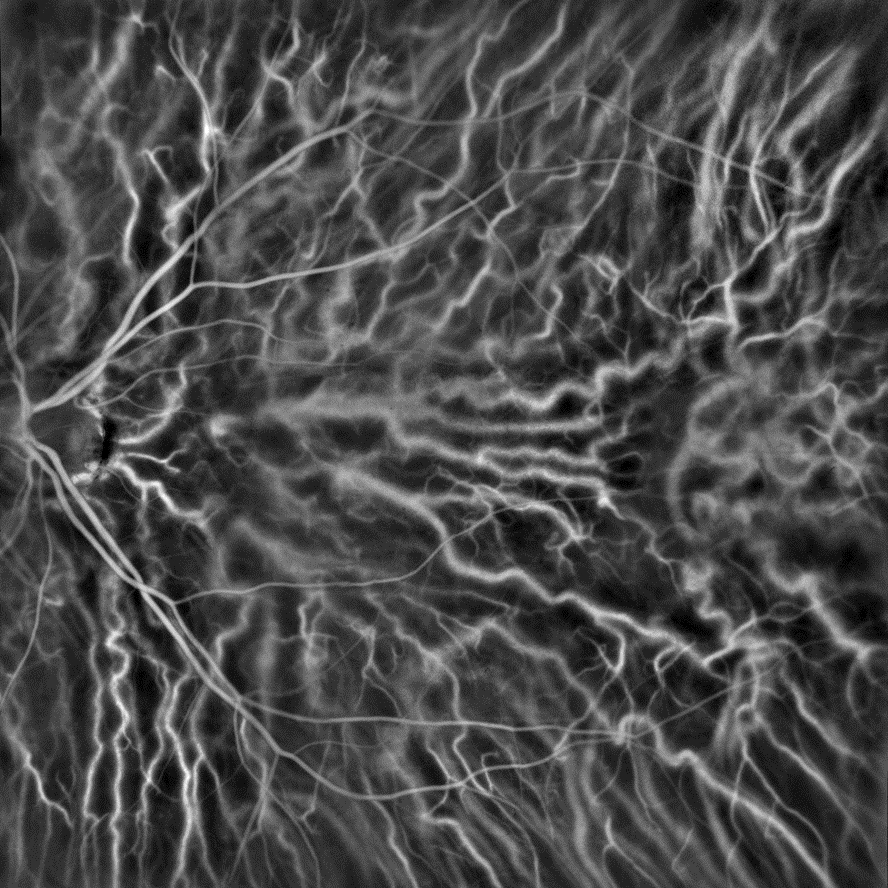

Tineke is Flemish-born artist who lives and works in Walyalup/Fremantle. She has a unique relationship with scientific research that helps her to see the massive in the microscopic. Something as small as the blood vessels in a horse’s eye could evoke a system of rivers and streams stretching across a vast expanse of land.

Right now, her art exhibition Tributaries is being toured in the South-West by Art On The Move. It highlights a strong theme across more than 10 years of her work: the arterial systems that carry life in rivers and delta systems as well as animal bodies. By revealing the branching structures that support life from the cellular to the global scale, it provokes questions about the place of human life in the broader ecosystem.

Tineke sees her practice as a process of discovery and exploration that’s just as motivated by curiosity as it is by the beauty of the systems that sustain life.

SMALL BEGINNINGS

Tineke’s interest in arterial systems began in 2010 while she was working as an executive officer at the Lung Institute. She was inspired by images of cell life and death that came about through the research facility and decided to make a cast of the lungs of one of the mice that was, in her words, “sacrificed for human medical science”.

She secured a residency at SymbioticA, UWA’s biological arts lab, and was coached remotely by a veterinary scientist at the University of Ghent in Belgium to learn the process of corrosion casting. “I love working with scientists,” she says. “I don’t cast just for the sake of casting. I want to tell a story about what our environment is doing as we fail or manage to take decisions about its protection.”

In the past, corrosion casting used anything from gelatin to insect larvae to reveal the intricate structures of organs in humans and animals. It was not exclusive to scientists. When it was first documented in the 17th century, the term “scientist” didn’t exist yet, and the casts were created as much for their beauty as their educational value. Anatomists were learning through collaboration across artistic and research disciplines – a rich intersection that continues to inspire practitioners like Tineke.

CASTING CORPSES

Today, the process of corrosion casting has been refined and almost exclusively uses a resin called Batson’s #17, but the key requirement has not changed: you need a corpse.

Tineke’s process begins with asking an expert on whatever animal she’s working with to perform surgery to drain the blood, ensuring the vessels are left intact (any lesions will allow the resin to leak out and ruin the cast) and clear the way to the heart. Tineke then mixes the resin with pigment and injects it through the heart so that it spreads throughout the pulmonary system.

This is left overnight to set, and the next day, the whole animal is submerged in potassium hydroxide, which slowly dissolves the body and usually the bones. The body must be rinsed and have the acid changed regularly to ensure the tissue comes off cleanly and at the end nothing of the original creature remains – just a permanent plastic imprint where its blood used to be.

SEA CHANGE

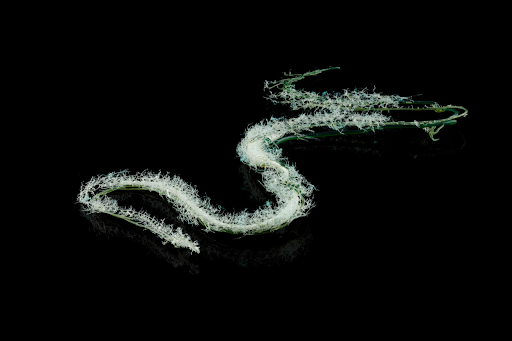

While Tributaries focuses on human relationships with life on land, Tineke’s next exhibition, Concurrencies, dives into our relationship with the ocean. It has roots in her recent collaboration with researchers at La Trobe who were investigating the impact of human-generated sound on the sensory capabilities of ghost sharks.

They found the noise pollution in the shark’s breeding grounds is so severe that it even damages the hearing of unborn sharks still in their eggs. At the end of the research project, the sharks that had been captured and studied were euthanised, and she began her casting process.

“There’s such a sense of exploration and bringing new information to light from this process,” says Tineke. “What the scientists did discover in the cast we made of the ghost shark is that its reproductive system is all beautifully there, the vasculature around it, and they’d never seen that before.”

Tributaries is showing until 28 August at the Museum of the Great Southern in Albany, and Concurrencies will open at the Alister Yiap Gallery in Perth from 9–25 August.