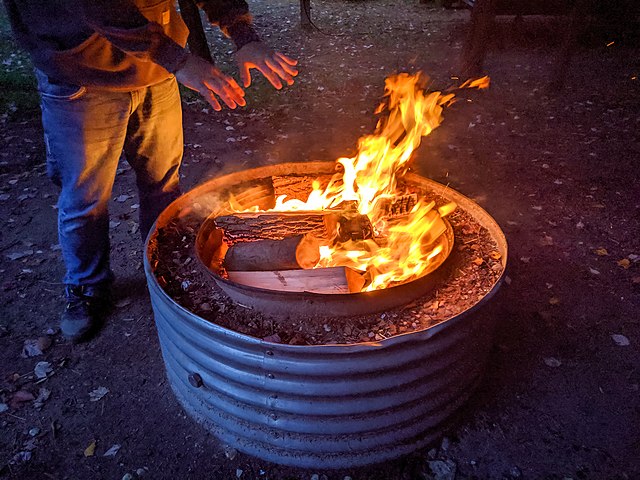

For millennia, as flames licked into the night air, we’ve gathered around a central fire to cook and share stories with those around us. It’s a scene as old as humanity itself, but how did fire come to be such an intrinsic part of our lives? And why do we still feel so drawn to it?

IN THE BEGINNING

In humanity’s early beginnings, fire was only used for warmth. but about 800,000 years ago, we began using fire for cooking. Cooked food complemented our expanding diet of fruit and nuts, letting early humans get more nutrients from their food by making it easier to digest. It also let us eat a wider variety of foods.

“You can think about trying to eat an uncooked potato. The impact of fire on making that food more available was probably even greater than the impact on animal food stuffs like meat,” says Associate Professor Debra Judge, a biological anthropologist from the University of Western Australia.

And as we got more nutrients in our diet, our brains began to develop at a faster rate.

“Brains take a lot of energy to run, and they take a lot of energy to develop. Different kinds of food allowed that development to happen,” says Debra.

As our brain size and capacity increased, we got even better at finding food and using fire efficiently. And with better food, humanity continued to evolve and grow more intelligent.

FIRE AND THE MIND

As humanity grew, fire became so ingrained in our way of life that we may even have developed a physiological response to it.

In 2014, a study on 226 college students from the US found that the sight and sound of an artificial campfire measurably lowered people’s blood pressure.

Researchers aren’t entirely sure why this happened. It may have been an innate psychological trigger or perhaps it’s a socially learned response to a relaxing situation.

Unfortunately, the study’s results have never been replicated. And with the study having used artificial fires and such a small sample group, it’s difficult to draw any definitive conclusions.

But despite not knowing how these results came about, Debra believes the important thing is why.

“How the physiological response works isn’t the issue. The fitness outcomes in terms of evolutionary biology and why we respond that way, that’s what’s important. If you have something that gets people together in a way that results in physiological or psychological benefits, then that’s a benefit of fire,” says Debra.

And relaxation isn’t the only way that communal fires have shaped the human mind.

As fires allowed humans to be awake longer into the night, it may have permanently altered our sleep pattern. Some researchers suggest that it led to our sleep cycles being shorter and more efficient, with more time in REM sleep. This may have allowed for improved memory and skill retention.

HEARTH AND HOME

Those extra hours of light that early humans created via fire also had an effect on our society and culture. Our hearths became places for evocative and meaningful conversation.

Research on hunter-gatherer communities in southern Africa found that fireside conversations “evoked the imagination, helped people remember and understand others … healed rifts of the day, and conveyed information”.

That intimate setting where expressive conversations and meaningful connection can be had is as important now as it has ever been.

“That central fire brings people to one place and facilitates the kind of social learning that we do through telling stories and singing of songs that pass information,” says Debra.

THE STORY OF FIRE

As our food, communities and lives came to revolve around fire, it also became a central feature of myths, legends and folklore around the world, including right here in Australia.

Noongar stories from southwest Western Australia tell that fire keeps away dangerous spirits called Mummaries. In the northeast of Tasmania, an Aboriginal story tells that two stars brought fire down from the Milky Way to warm and heal people.

On the other side of the world, a Greek myth tells of the titan Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods to give to humans.

Fire is synonymous with humanity, and these stories can tell us a lot about who we are.

“If you have myths about fire, it’s not an objective recording of history, but it is a recording of what people find important about their history,” says Debra.

The story of humanity is the story of fire, and that is a story we all share. So the next time you’re watching the flames shift and change while you share stories with friends, remember that you are taking part in an act that is as old as humanity itself.

Humans have a special relationship with fire.

To find out how much it impacts our lives and our landscapes, check out the second season of the Elements podcast.

All episodes out now on all your favourite podcast platforms.