If you’ve ever had a burn injury, you’re not alone. There are around 50,000 burns-related hospital admissions in Australia each year, according to the Australian and New Zealand Burn Association.

Even minor burns can lead to chronic pain, scarring and psychological stress. Sadly, children under 5 have the greatest risk of serious burn injury – usually caused by contact with hot drinks, food, fats and cooking oils.

Getting to the heart of it

Scientists are still learning about the long-term effects of burns on the body. UWA researchers recently reviewed studies showing burns could impact an unlikely organ – the heart. Now they’re searching for the cause.

The review found burn patients had a higher rate of cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovascular diseases include heart blockages, strokes and artery and aorta issues.

Even small burns covering less than 10% of the body increase the risk. But why would a burn on, say, your arm affect your heart up to 30 years later?

Tiny blood cells with a big job

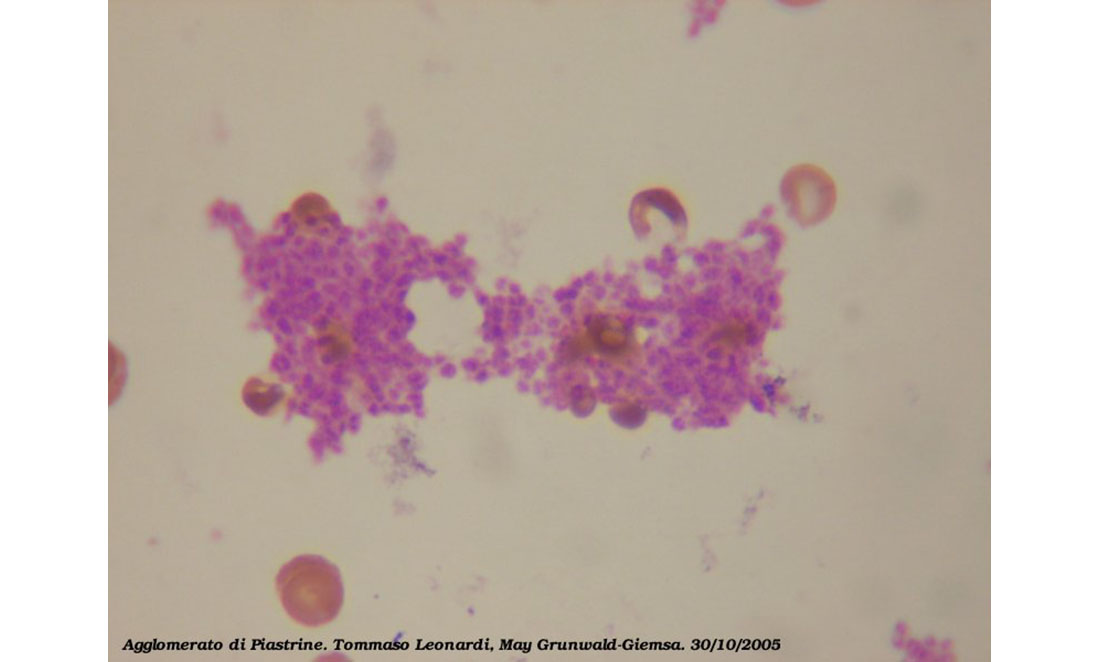

Platelets might answer this question. The smallest of our blood cells, platelets control blood clotting to heal wounds. They only live for about 9 days.

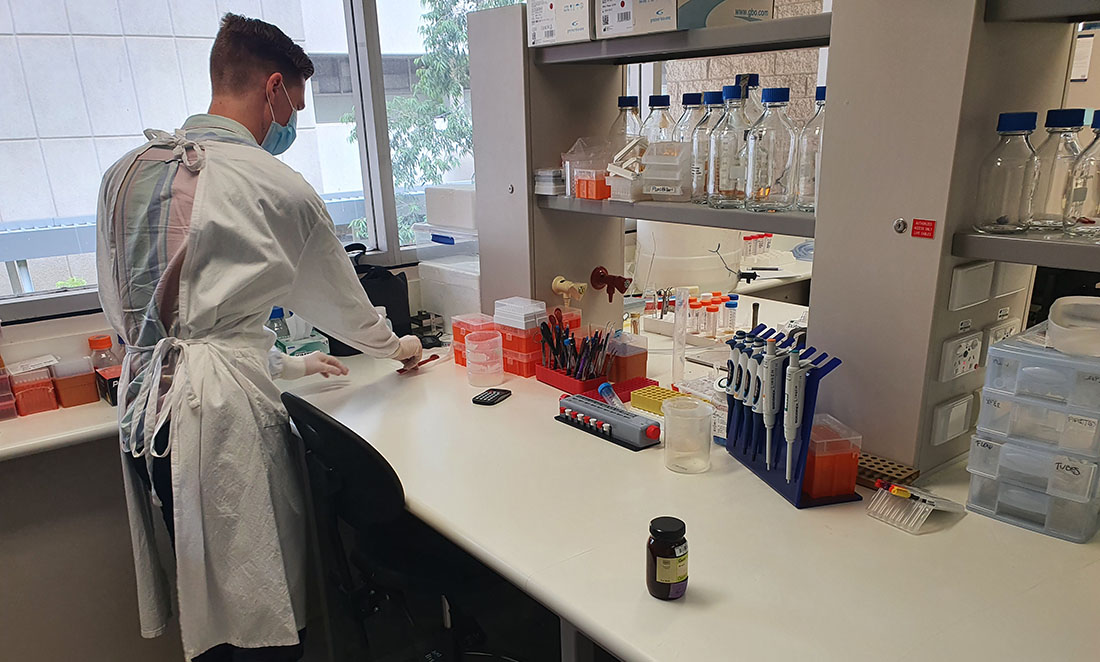

Associate Professor Matthew Linden was one of the leaders of the UWA review team. He supervises PhD student Blair Johnson, who researches how platelets behave after a burn injury.

“If there is persistent platelet dysfunction years after an injury, it suggests there is something continuing to disrupt those platelets,” says Matt.

“Either they’re reactivated or they’re produced in a different way. We’re looking for these physiological scars.”

While burns don’t usually bleed, a crucial part of wound healing involves constricting nearby blood vessels. By closing the vessels, the body can isolate damaged areas for repair. Platelets perform several jobs in this process.

How do platelets help with burns?

Shortly after a burn, damaged blood vessels release proteins that bind nearby platelets. The platelets and blood vessels then trigger inflammation. This attracts monocytes – a type of white blood cell involved in the immune system. These monocytes attach to the platelets and use them to pass through the blood vessel wall.

This is an important step for healing the damage caused by the burn, as monocytes transform into cells called macrophages that clean up dead tissue and protect against infection.

However, the same process can cause the monocytes to move into the cell wall, where they can become foam cells, creating plaque. Plaque build-up is a common issue with heart disease.

One theory is that disruption of blood flow following a burn could cause ongoing activation of platelets and build up of plaques over a period of years.

Another possibility is scarring in the bone marrow leads to long-term changes in platelet formation. Like red and white blood cells, platelets form from progenitors in bone marrow.

“At 28 days after a burn, we can measure whether there’s a persistent change in platelets. In mouse models, we can measure bone marrow and search for scarring,” says Matt.

“Platelets have a very short circulating half-life. After 9 days of recovery, the platelets shouldn’t carry memory of the injury, but they do.”

Pain could also contribute to heart disease. Burn survivors can experience long-term stress, pain and psychological trauma. Long-term chronic illness makes you vulnerable to other diseases.

“Emotional stress is physical stress. The emotional response to ongoing pain changes cortisol levels and then changes to catecholamines.” (Catecholamines are produced by our adrenal gland and prepare our bodies for fight-or-flight response.)

“These have clear and measurable effects. It’s plausible that ongoing chronic adrenergic response [platelets response to adrenaline] could activate platelets over many years.”

A bloody race against the clock

Blair’s testing this theory in mouse models and clinical trials with burns outpatients from Fiona Stanley Hospital. It’s tricky because platelets clot when they leave the body.

To prevent clotting, an anti-coagulant called sodium citrate is used. If you saw a blue vial when you had a blood test, it mixed your blood with sodium citrate. This chemical binds to calcium ions that would otherwise activate platelet clotting.

This gives Blair 30 minutes before the platelets start clotting, so he races the samples to the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research for testing.

“Once they’re out of the body, the platelets get active and start to look less like they do in the body,” says Blair.

“Quite often, we're trying to get our reaction started 15 minutes after we take blood.”

Further research is under way to better understand the link between burns and heart disease. The findings could help doctors treat burns patients in the future – and lead to big improvements.