How do you feel today?

For some people, it’s an easy question to answer. You might be amazed, angry, annoyed, anxious or ashamed.

But for others, describing their emotions can be much more difficult.

It turns out there are differences in how good we are at identifying and describing our own emotions. And these differences can vary vastly between people.

No words for emotions

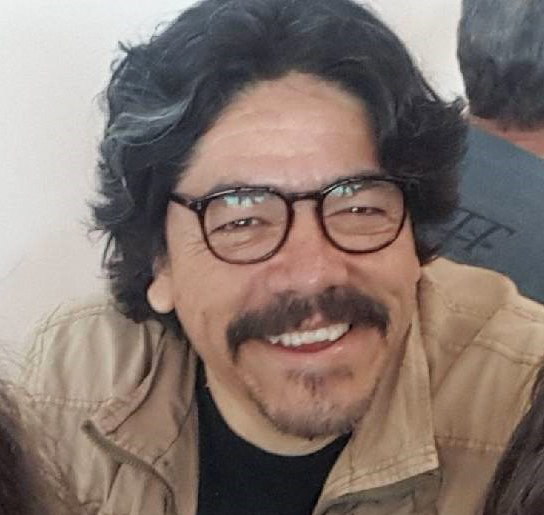

Clinical psychologist and UWA Associate Professor Rodrigo Becerra is an expert in alexithymia – or emotional blindness.

“It’s not a condition or an illness, but it’s a personality feature that some people might have more than other people,” he says.

“It’s characterised by difficulties in identifying your own emotions and describing your own emotions.”

Rodrigo says alexithymia can be placed on a continuum – some people are very good at identifying and describing their feelings while others are not.

And it’s totally different from not having emotions at all.

Rodrigo says emotional blindness can make people vulnerable to mental or psychological difficulties. For example, if people are having issues with anxiety and depression, alexithymia can make therapy more challenging.

“Emotion is the currency of therapy,” Rodrigo says.

“If you don’t have an ability to identify those emotions really well and express them or communicate what you are feeling, then of course [therapy sessions] are going to be a bit more laborious.”

Rodrigo says alexithymia can also pose difficulties in everyday life, such as in relationships, where it helps if you can fluently communicate how you feel.

In search of a cause

Rodrigo says some people have had emotional blindness their entire lives. But often these people don’t notice it and only seek help when referred by a partner.

Rodrigo says that, while there’s no single cause for emotional blindness, part of it may be related to our upbringing.

“We think that there might be people with high levels of alexithymia who were probably brought up in an environment where expression of emotions wasn’t a rewarded or a welcomed skill,” he says.

“[If] you’re a child and you say ‘I feel this’, and that provokes a healthy exchange and communication, that’s probably going to make you more open to identifying your emotions.”

Rodrigo says it’s also possible for emotional blindness to be caused by changes in the brain, such as a brain injury.

He believes this can happen where there is damage to the frontal lobe – a part of the brain responsible for abstract skills including inhibition, cost-benefit analysis and emotional regulation.

Putting emotions to the test

So how do you find out if you’re emotionally blind?

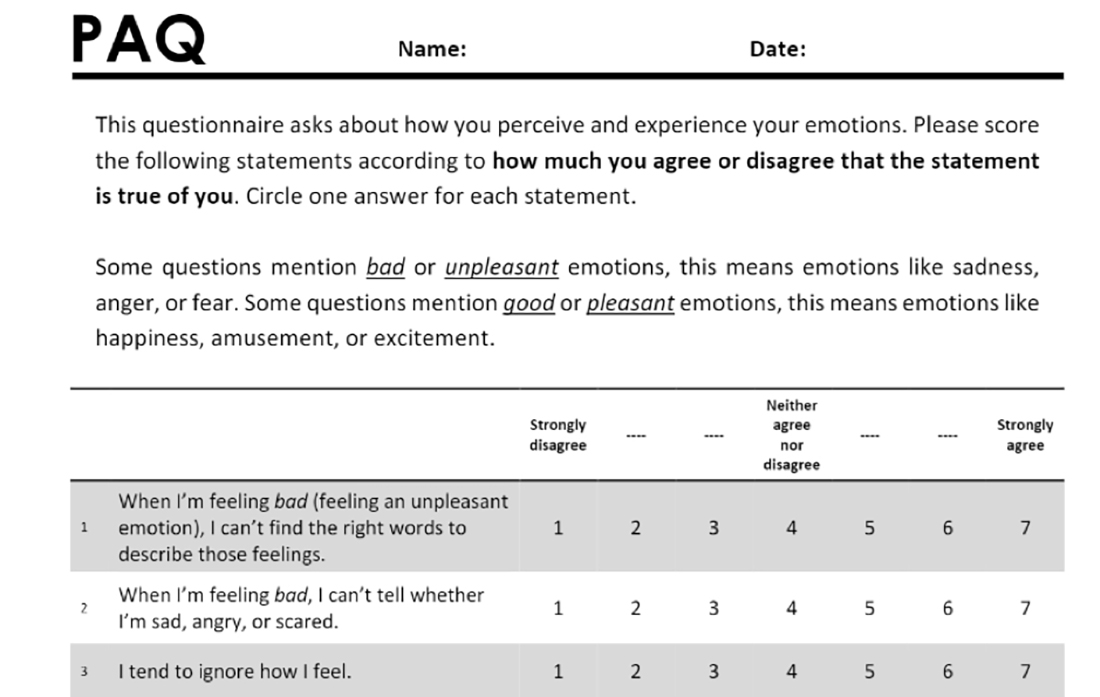

Rodrigo and his colleagues, including Curtin University research fellow Dr David Preece, developed the Perth Alexithymia Questionnaire to test for emotional blindness.

It’s the first assessment tool in the world designed to test all aspects of alexithymia across both positive and negative emotions.

That’s important because some people might be good at identifying positive but not negative emotions or vice versa.

The 24-item questionnaire has been picked up by researchers around the world and translated into Polish, Italian, French, Indonesian and Spanish.

Rodrigo says if emotions are very strong, people with alexithymia can usually still identify them.

“If you’re very angry, you’re furious, you’re red in the face, I think everyone knows that’s a very bad episode of anger,” he says.

“But usually in normal life, emotions are not as florid and dramatic.”