Ask a scientist why they got into research in the first place, and a lot of the time, you’ll find it has something to do with ‘impact’.

(Lord knows they’re not doing it for the money.)

For many scientists, the end goal of their life’s work is to change the world for the better.

On top of any number of goals a scientist may have for themselves, there’s now increasing pressure for them to demonstrate that their work provides a benefit to society. After all, much of the research being done across Australia is funded by tax-payers’ dollars. We should be getting something out of it, right?

One way for scientists to turn their lab-based theories into real-world solutions is to influence policy in some way. In an ideal world, scientific evidence would be taken into consideration by our governing bodies and used to inform policies like this environmental offsetting strategy.

But in case you haven’t been paying attention lately—our world isn’t always ideal.

The policy process is complex. It’s fraught with politics and competing interests, and decisions are often influenced by cultural, social and economic ideas.

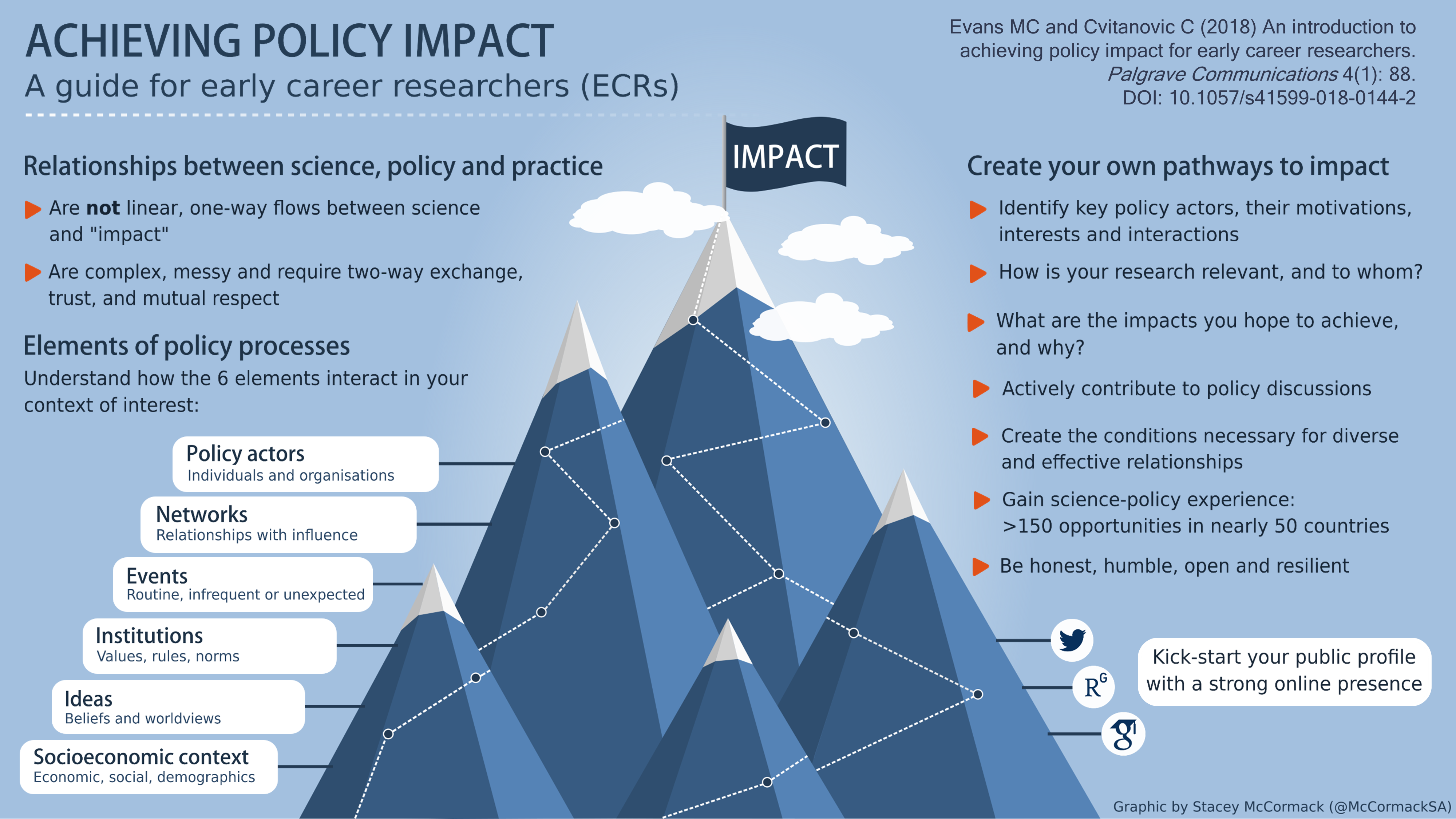

Navigating all of this is not easy. This is especially true for early career researchers (ECRs) who already have their own unique challenges to face. Faced with low job security, limited positions and heavy reliance on their professional networks, understanding how to achieve impact in the policy space is particularly difficult for ECRs.

And it’s certainly not something they teach at uni.

Dr Megan Evans of the Centre for Policy Futures at the University of Queensland, along with her colleague Dr Chris Cvitanovic of CSIRO, saw this was a problem. If early career researchers can’t contribute to the policy process, society doesn’t get to benefit from their experiences, insights and expertise.

So, based on their own experiences working at the intersection of science and society, Megan and Chris published their own paper to help ECRs achieve the impact they hope for.

TRICKS OF THE TRADE

The one key takeaway from this paper?

“Impact can be many different things,” says Megan. “There’s no one-size-fits-all approach.”

It’s also messy. There’s no clear-cut path from science to impact. Impact also looks different to everyone.

“Policymaking has, on many occasions, been likened to making sausage. You’ll like it better if you don’t watch how it’s made too closely.”

But there are ways to manage this messiness. Megan and Chris’s paper clearly details the many things that early career researchers can do right from the start to improve the likelihood that their research will be incorporated into policy.

It includes practical, achievable tips like figuring out what you actually want to achieve and building your social media platform.

This advice might seem relatively basic. If making a difference in the world was what inspired researchers in the first place, why don’t more of them know how to do it?

PUBLISH OR PERISH

Megan says that the incentive systems built into academic institutions are one of the barriers preventing early career researchers from making a real impact in the world.

Tenured or permanent positions at universities are highly sought after by academics. Having a tenured position means that the researchers can only be dismissed from the role for really extreme circumstances.

To be awarded a tenure position at a university, researchers often have to demonstrate a long and illustrious career of publishing articles in influential journals. The more citations these papers receive, the more impact they are deemed to have. However, this sort of impact is mostly just a measure of how many people are talking about this research. It has no correlation with any change in the real world.

The pressure to publish is demanding, and it means that, for the bulk of a researcher’s career, they must ignore any desire to have a real-world impact. Even when putting together this new paper, Megan found that many advanced researchers saw societal ‘impact’ as something to be addressed only “once you get tenure”.

“The advice is well meant but not forward-looking,” says Megan.

“They’re assuming that we want to achieve what they’ve achieved.”

But this couldn’t be further from the truth.

A REAL NEED FOR REAL-WORLD IMPACT

The desire to have genuine impact became abundantly clear in a forum held last year where discussion centred around how researchers could engage meaningfully with big societal questions about the environment.

Chris was presenting at this forum. As someone with experience working as a policymaker, knowledge broker and researcher, he had valuable insights to share and probably expected a bit of engagement with his audience.

But he was overwhelmed by the number of people who approached him after the presentation seeking more information. The majority of them? Early career researchers.

They all wanted to know what they could do to make a difference. This was the catalyst to write the paper .

Since being published, Megan and Chris’s paper has been tweeted over 800 times. Megan says she’s received dozens of tweets and emails thanking them for their work. While it’s not recognition in the traditional form of citations, it’s clear the real-world impact of this research has been felt.