Five years ago, Dr Qi Fang’s research society won a Nobel Prize for the first observation of gravitational waves.

Now, the physicist is making waves of his own with a tool designed to help doctors find cancer during surgery.

The creation recently won Qi the Woodside Early Career Scientist of the Year Award at the 2022 Premier’s Science Awards.

According to Qi, most surgeons are currently using their finger to feel for cancer.

“Normally, cancer will feel stiffer than the healthy tissue,” he says.

“So by touching that tissue and also by visualisation, normally a surgeon can find the big cancer.”

However, the method is not the best when it comes to finding and removing smaller tumours.

Seeing the light

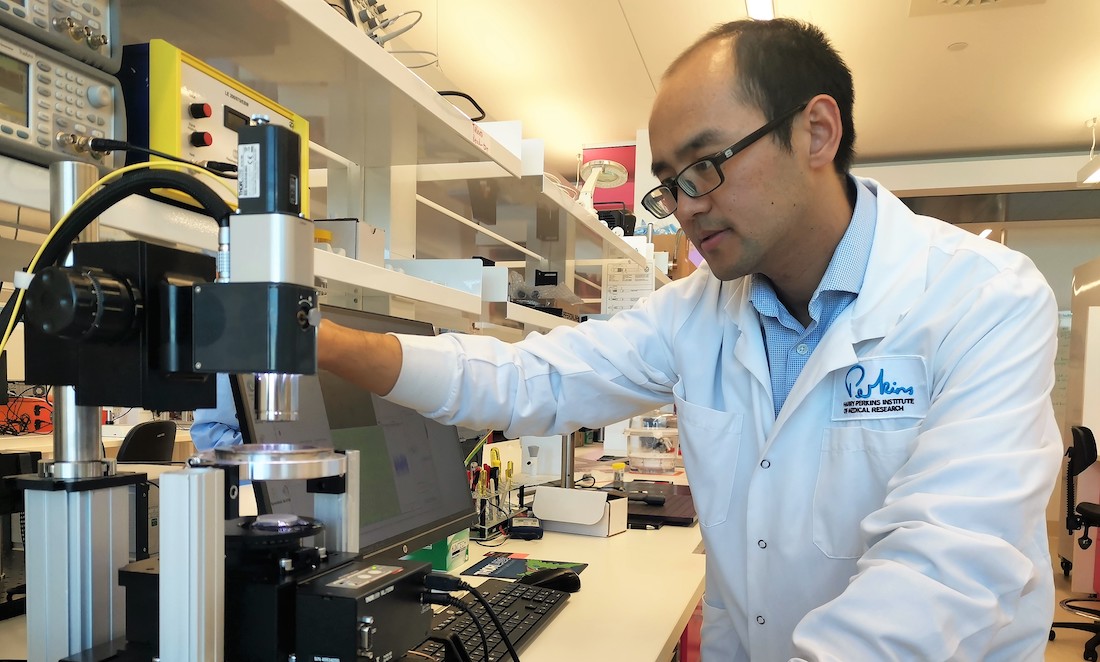

Qi is currently based at UWA and the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research. His latest creation is a tool that uses infrared light to detect cancerous tissue.

“We will be able to use the light to find out the stiffness of the tissue,” he says.

“This technique is more quantitative and also more objective.”

The research is focused on breast cancer – the most common type of cancer in Australia. According to Cancer Australia, over 20,000 new cases of breast cancer will be diagnosed in 2022.

For most, treatment will involve surgery to remove a tumour from the breast.

Qi says that, if the cancerous tissue is completely removed during the first round of surgery, the patient’s prognosis is good.

But about one in four people will need a second or third surgery to fully remove the tumour.

“With this technique, we hope to help surgeons find … a very small cancer,” Qi says.

“Then the surgeon can cut out the cancer for patients in one-stop surgery.”

The results of the first clinical trial of the technology are set to be published in the coming months.

the long and short of it

Qi started his STEM career in astrophysics.

He spent his PhD searching for black holes and gravitational waves using a laser interferometer. It’s an instrument that uses two beams of light to make precise measurements.

Qi’s research society LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory) even won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2017 for the first observation of gravitational waves.

But with a young family, Qi wanted to move into an area of research that wouldn’t require frequent time away at an observatory.

That’s when Qi found a research group trying to improve cancer imaging with a light interferometer – a smaller version of the technology he had used to look for black holes.

“The difference is only the scale,” he says.

“For a gravitational wave detection, we were doing a very large-scale interferometer … 4 kilometres long.

“In the cancer imaging technique, the interferometer is very, very short – it’s about several centimetres long.

“But the technique behind it is very similar.”

Accessible tech

While Qi’s cancer imaging technology is being commercialised, he’s working on a new project that uses a digital camera to detect the ‘stiffness’ of the cancer.

While not as powerful as the infrared probe, it’s much, much cheaper.

Qi says a digital camera probe (pictured above) might cost a few hundred dollars compared to more than $100,000 for the infrared device.

“This project can be used not only in metropolitan hospitals but also in rural areas and … around the world,” he says.

“Every hospital can afford that. That’s the very exciting part for me.”