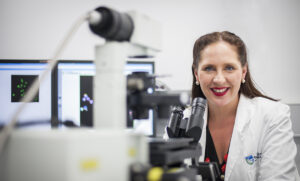

Marianne Nyegaard’s PhD research started out simply enough.

The Murdoch University student wanted to look at the impact of tourism on sunfish near Bali.

But when she started testing small skin samples to see which sunfish species they were from, she kept finding samples that didn’t match any known species.

What followed was a 4-year treasure hunt that saw her search for sunfish in museums around the world, on social media, in books dating back to the 1500s, in New Zealand and on WA’s south coast beaches to find a match.

SUITCASES WITH WINGS

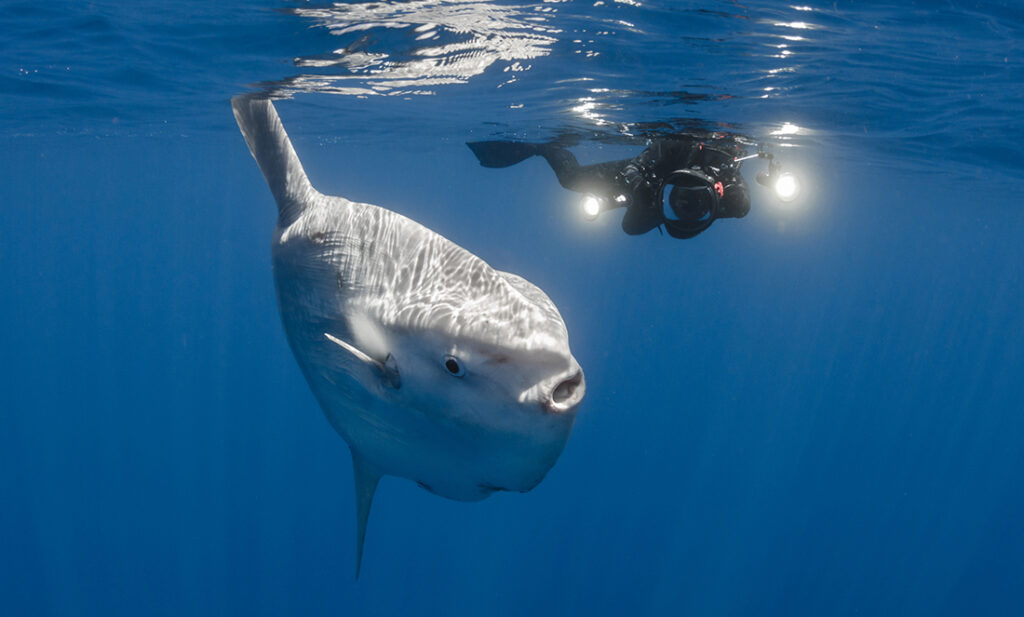

The apple of Marianne’s eye is famous for being huge and, well, a bit weird looking.

They can grow to more than 3 metres long and weigh up to 2 tonnes—roughly the weight of an average SUV.

Sunfish have flat bodies, no tail and almost symmetrical fins above and below their body.

They’re so odd looking that they’re sometimes likened to suitcases with wings.

“Everything about sunfish is kind of weird,” Marianne says.

“Because they look so strange and they’re quite elusive—you don’t see them every day—all these things combine to make them super exciting to study.”

Marianne says we think sunfish evolved from reef fish that adapted to life in the open ocean.

“They’ve got no defence out there,” she says.

“So what they’ve done to adapt is they grow really large—they grow so no one’s mouth is big enough to eat them except for sharks and orcas.”

Sunfish also move weirdly.

“They fly through the water like a bird,” Marianne says.

“They don’t move through the water like a normal fish that would gain thrust with the tail. Instead they gain both lift and speed with these wings.”

THE HOODWINKER SUNFISH

To cover more ground, Marianne wanted to compare the sunfish she was studying in Indonesia to those in Australia and New Zealand.

She started getting biopsy and skin samples of sunfish from the fishing industry and realised she had a new species on her hands.

“That was of course incredibly exciting, and all I had were these little skin samples,” she says.

“So it was quite tantalising to go on the hunt for this unknown fish.”

Marianne started looking at photographs of sunfish, especially on social media, to see if she could spot anything different.

She developed a network of people who could tell her if a sunfish was caught or washed up on a beach.

Finally, Marianne got her big break when fisheries observers hauled a tiny sunfish on board to free it from a fishing line and got a great photo of the undescribed fish, along with a genetic sample.

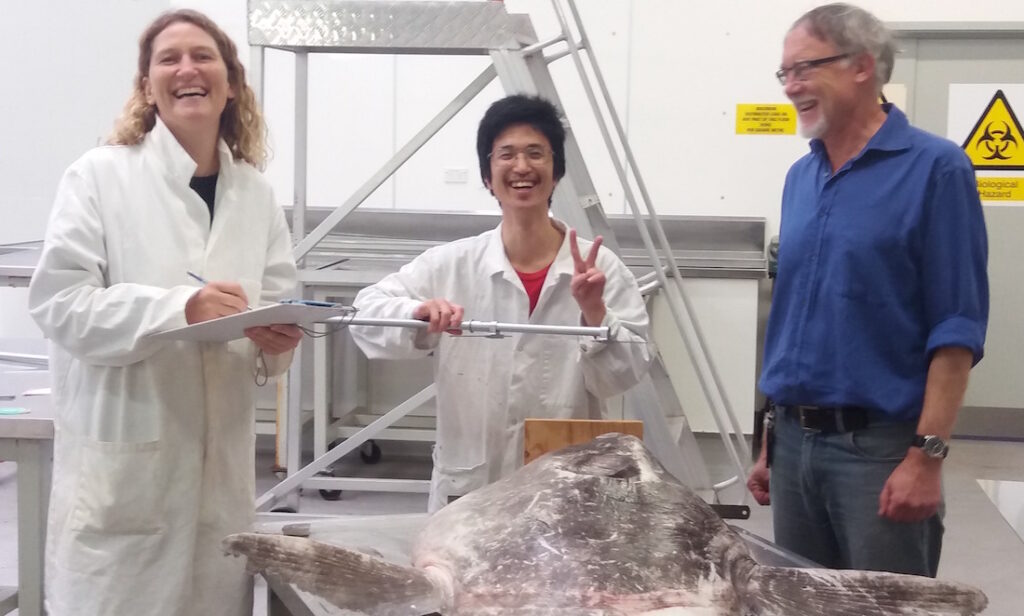

Shortly after, by a crazy coincidence, four of the undescribed sunfish were stranded on a beach in New Zealand.

Marianne had her new species. She named it the ‘hoodwinker sunfish’.

TAXONOMIC CAN OF WORMS

The discovery of the new species helped clarify a taxonomic can of worms among the Mola sunfishes.

Marianne and her collaborators re-examined a branch of the sunfish family tree, the genus Mola, to see if there were any other mix-ups.

One species, known as Mola ramsayi, was thought to live only in Australia.

But they found a long-dead Mola ramsayi in a museum in Italy.

“It was in an old stairwell and it had chewing gum in its mouth and its taxidermy was antique,” Marianne says.

“But it was quite a big moment … when we found it.”

The researchers went through the scientific literature dating back to the 1500s to see who had first described the species and what it should be called.

They found sunfish in books that included mermen and unicorns, with one of the first written mentions coming from Pliny the Elder.

The result is that our Australian sunfish Mola ramsayi already had another name—Mola alexandrini.

Sometimes when you gain a species, you lose one too.