It’s not a spooky Halloween prank. It’s not a mutant caused by radioactive waste. It’s not an alien from Star Wars, and it’s not a sign of the end times.

It’s a perfectly normal lizard – it just happens to have two tails.

So what on earth is going on?

Dropping the base

As you might know, some species of lizards can drop – and then grow back – their tails. According to PhD student James Barr from Curtin University, it’s usually a way of escaping predators.

“If a lizard is grabbed by the tail it can drop – or for some species it can actually drop without it needing to be grabbed. They can then escape as the tail then thrashes around distracting the predator,” he says.

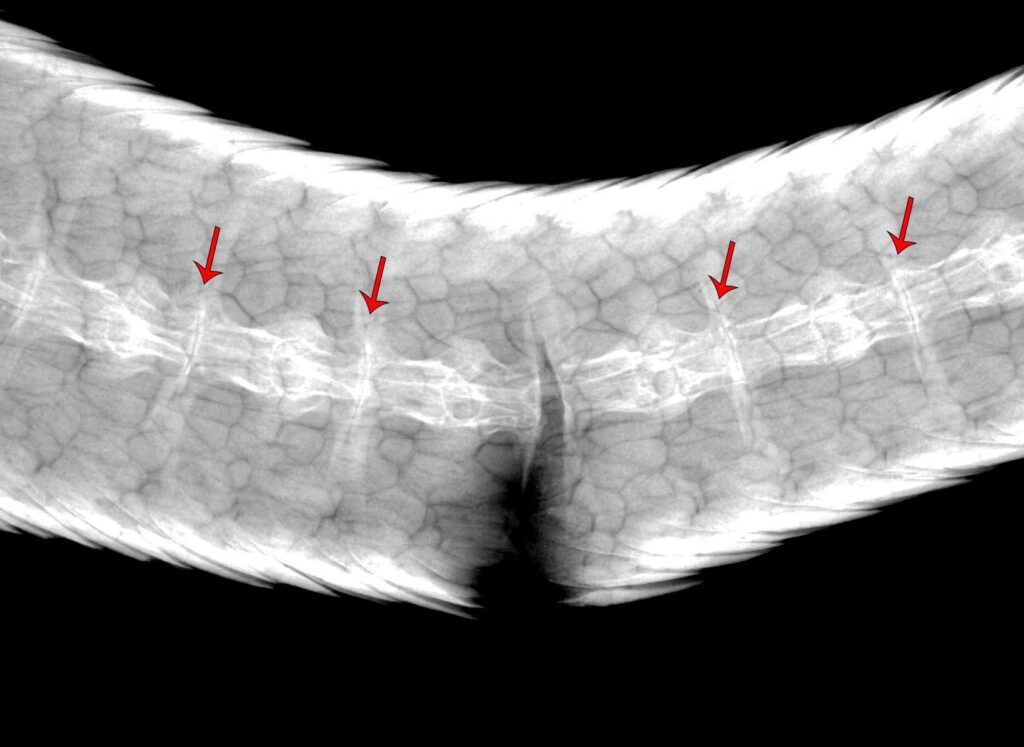

Growing extra tails is basically a glitch in that process. It’s either because the drop hasn’t gone quite to plan, or because the lizard has been injured.

“If something chomps on their tail, and gets deep enough to puncture a certain area of the spinal cord, that can kick off the regeneration process as well,” says James.

They’re not limited to just one extra tail either. If either tail gets injured again, the process can start all over again.

“It can kind of go a bit awry, depending on how many times it’s been chomped or tried to drop it,” says James

Too many tails on the dance floor

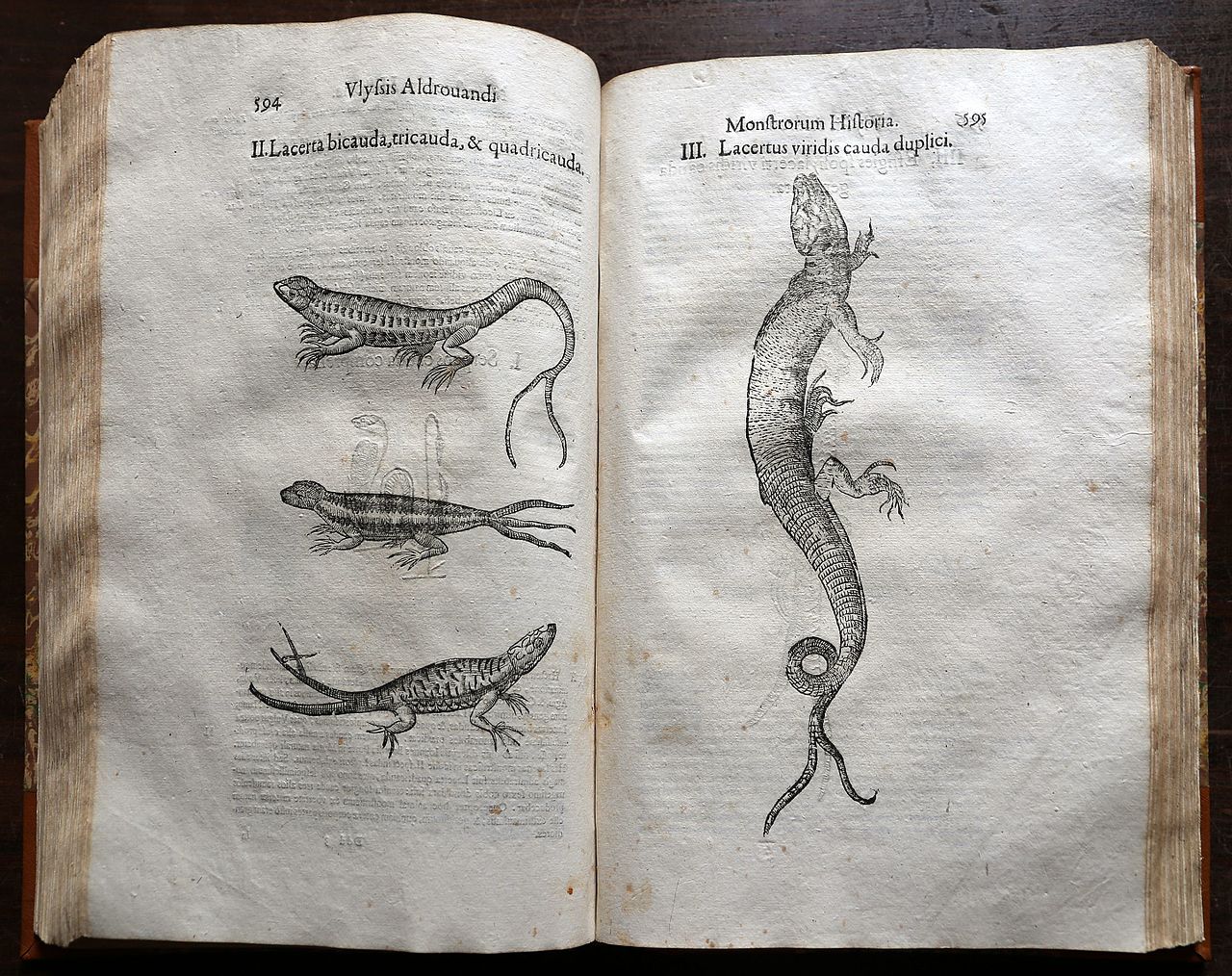

James’ research looked at 366 reports of multi-tailed lizards, dating all the way back to 1586. The record for most tails goes to a lizard from Argentina discovered in 2014, with a total of six – yes, six – extra tails.

Thanks to that research, we’ve also got a better idea of how common extra tails are. If you’re out walking through the bush, around 2–3% of the lizards you see could to have an extra tail or two. If you’re a lizard reading this, and you’ve previously dropped your tail, you’ve got around a 6–7% chance of growing a bonus one back.

What’s not as clear is what that actually means for the lizards.

“Long story short, is that we actually don’t know,” says James.

“Like, if they have to run through thick vegetation, could they get snagged?” he says.

“And if you’ve got, you know, an extra 50% of tail, you’re going to be carrying a lot more weight.

“But no one, as far as we are aware, has actually tested these theories.”

Is that an extra tail, or are you just happy to see me?

One way to figure that out, James says, might be to temporarily stick 3D-printed tails to regular lizards. It’s easier than trying to catch enough multi-tailed lizards in the wild. Plus, it’s probably nicer for the lizard – unlike a real split tail, these would fall off as the lizard sheds its skin.

That’s assuming, of course, that the lizard sees the extra tail as a detriment.

“It might go the other way. Maybe approaching a female it would be like, ‘Oh, you’ve got two tails there, this is interesting’. They might actually get some sort of benefit out of it, we just don’t know”.

Sounds like this research still has a tail or two left to tell.