When you think ‘wildlife poaching’, you’ll most likely think about elephant tusks and tiger skins – not carnivorous plants.

And yet the illegal collection of wild carnivorous plants is a lucrative business that could lead to the extinction of several species.

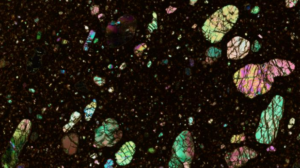

Carnivorous plants are typically found in harsh environments with nutrient-poor soils. They prey on insects and small vertebrates to supplement their diet.

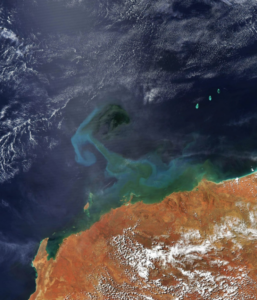

“In Western Australia, we’ve got some of the world’s oldest and most nutrient-poor soils,” says Dr Adam Cross, a botanist who specialises in carnivorous plants.

As a result, WA currently harbours the highest variety of carnivorous plant species on the planet. But many species, like the Albany pitcher plant (Cephalotus follicularis), are under threat from poaching.

So what’s driving the poachers?

One for the money, two for the show

According to Adam, plant poachers are driven by two things – money and ego.

Carnivorous plants are notoriously hard to grow, so some hardcore horticulturists use the plants to show off their allegedly superior gardening skills.

But sometimes, the fancy plant you really want to show off is only found on the other side of the world. Enter poaching.

“It’s big in Australia, but it’s nowhere near as it is in places like Indonesia, the Philippines or Borneo, where tropical pitcher plants are being completely decimated by illegal poaching activities,” says Adam.

And in recent months, due to the socioeconomic impacts caused by COVID-19, tropical regions have noticed a boom in plant poaching.

“There is very little else that some of these communities can do to make an income, but they can sell these plants to someone over in the US,” says Adam.

According to Adam and his colleagues, it’s common for researchers to receive requests from collectors for seeds or plants within days or even hours of new plant discoveries being documented. And in some instances, the newly discovered species are poached within the same timeframe.

“Much like drugs and other sort of illicit things, there are pretty sophisticated and complex routes for these activities. So, yes, unfortunately, it is a relatively or can be a relatively lucrative operation,” says Adam.

The bigger pitcher

So there are strange looking insect-eating plants out there in the wild. And they’re being poached. Why the heck should we care?

“You’re not only taking plants out of the wild, but you’re also damaging that habitat,” says Adam.

If carnivorous plants disappear, it would throw some things out of whack.

Like every other living thing, carnivorous plants have a specific role to play in the global food web.

“We rely on binary systems for just about everything,” says Adam.

“There’s a lot of examples all around the world of really amazing co-evolution of mutualism between plants and animals in carnivorous plants.”

One such example is the mutualism between the carnivorous pitcher plant (Nepenthes hemsleyana) and Hardwicke’s woolly bat that’s been observed in the forests of Borneo.

Furthermore, carnivorous plants can be a source of great inspiration for human innovation.

“Probably the most pertinent example is some of the non-stick surfaces on the insides of pitcher plants, which are being used as the basis for developing non-stick surfaces in cookware,” says Adam.

And with the added stresses of climate change and urban sprawl, if no action is taken to protect these fascinating plants, 25% of the world’s carnivorous plants are estimated to be at risk of extinction.

“We know of at least a couple of species here in Western Australia that have become extinct already,” says Adam.

And if you need more reasons for why we should be protecting carnivorous plants from extinction, tune into the Particle Podcast where Rose chats with Laura Skates, a WA botanist who specialises in carnivorous plants!