Hunting after dark, one species of WA bat can fly at speeds of eight metres a second.

The bat uses echolocation to detect prey, first sensing a meal when it’s only a few metres from its snout.

“It doesn’t get much time,” zoologist Norman McKenzie says.

“It has to calculate the trajectory and speed of its prey. It has to calculate the intercept point.

“It has to make that rather sharp turn [and] it must maintain its flight stability while it does it.

“That’s quite a trick – you’re looking at two, three, four [g-force] turns.”

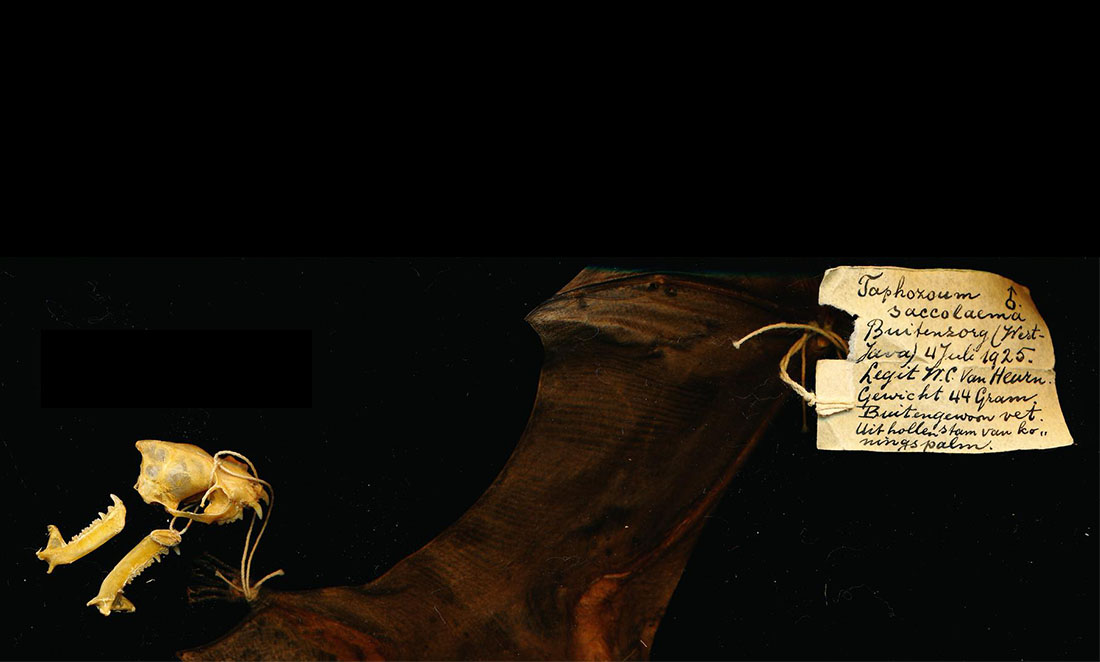

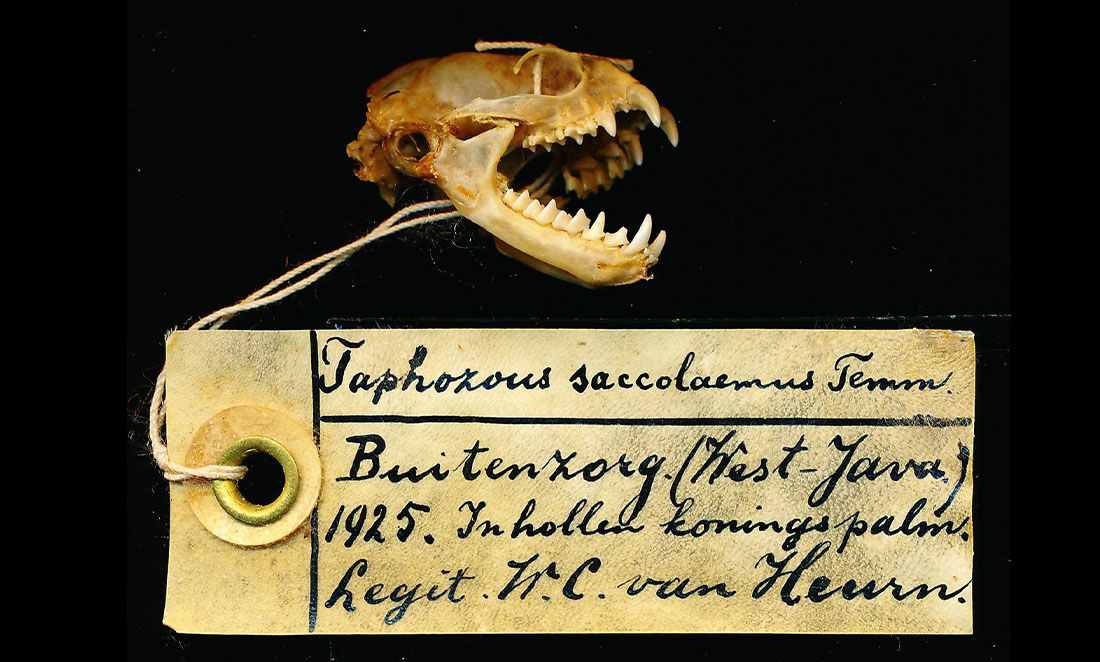

Sounds of the bare-rumped bat

Norman has been studying WA bats for four decades.

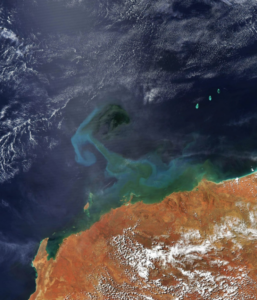

In one recent study, he analysed recordings of echolocation sounds made by bare-rumped sheathtail bats in north-western Australia.

(Confusingly, in WA these bats don’t actually have bare rumps).

Each high-resolution recording was fed through a sound analysis program.

It revealed data such as frequency and the time between pulses.

That helped the researchers work out the bats’ foraging niche and flight speed – useful in conservation planning.

The bat man

Bats first captured Norman’s attention as a zoologist conducting biological surveys around the state.

“We didn’t know a lot about them in the 1960s and 1970s when I was going to university and fresh out as a young zoologist,” he says.

Norman would watch bats catching insects in lights around his campsites.

And he’d see them while spotlighting for possums and bandicoots.

“In Western Australia when you go out into the bush … a lot of the animals you’re going to see at night are going to be bats,” Norman says.

“They’re often following the vehicle along because the headlights … are generating insect swarms.

“Which they’re attracted to instantly – it’s a quick feed.”

Great survivors

Norman was also interested in why bats have been more resilient than other Australian mammals.

“I was always involved in research on the status of mammals,” he says. “We knew even then we’d lost a lot, and we’re still losing them.”

“But [bats] are the group that’s persisted the best.”

The secret to bats’ survival?

“They hunt in flight,” Norman says.

“If you’re going to search a volume of space for food, it is 10 times more efficient to do it in flight than by walking or running on the ground or climbing trees.”

Echo, echo

Norman retired from Department of Parks and Wildlife in 2014 but remains active in bat research.

He says the echolocation study is an example of how recordings can help overcome some of the challenges of field observations.

“Field work’s terribly expensive … because you have to go out there and spend weeks and weeks [doing] night work,” he says.

“And it's hit and miss – they’re small, they fly fast.”

With bare-rumped sheathtail bats hunting at eight metres a second, you’ll be lucky to catch a real one this Halloween.