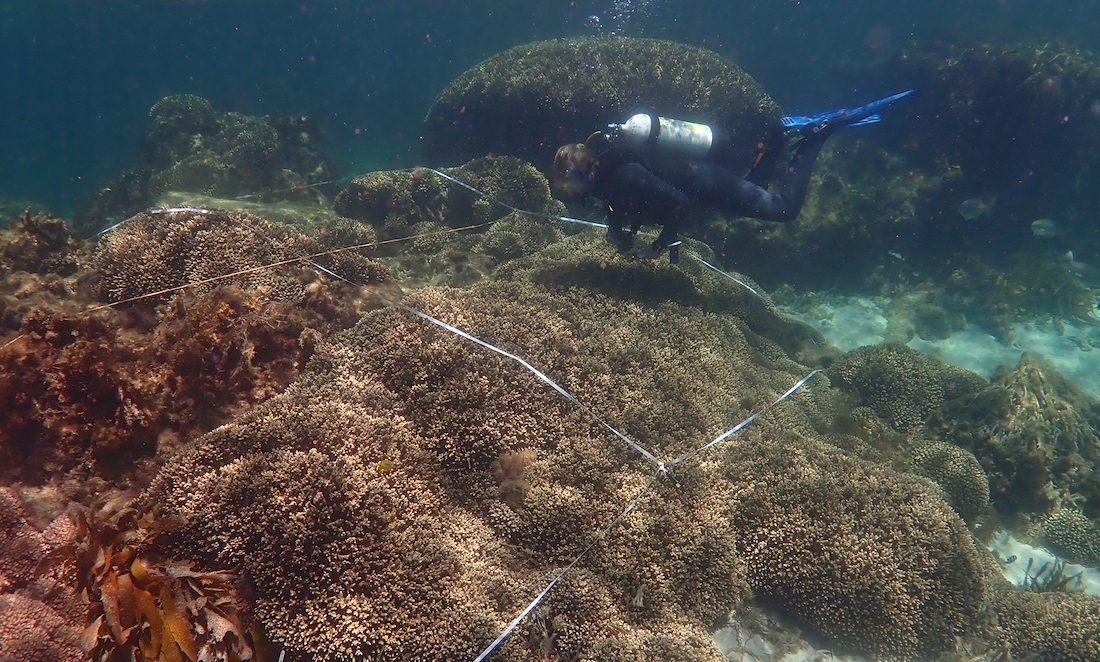

Every month, Murdoch University PhD student Veera Haslam dives into the ocean at Rottnest to search for Drupella cornus snacking on the island’s reefs.

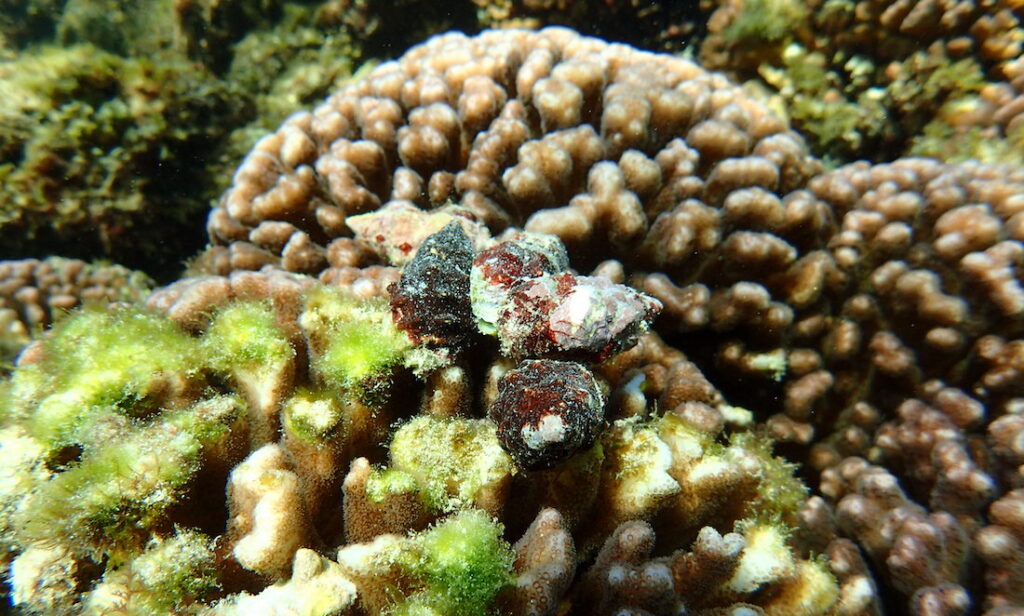

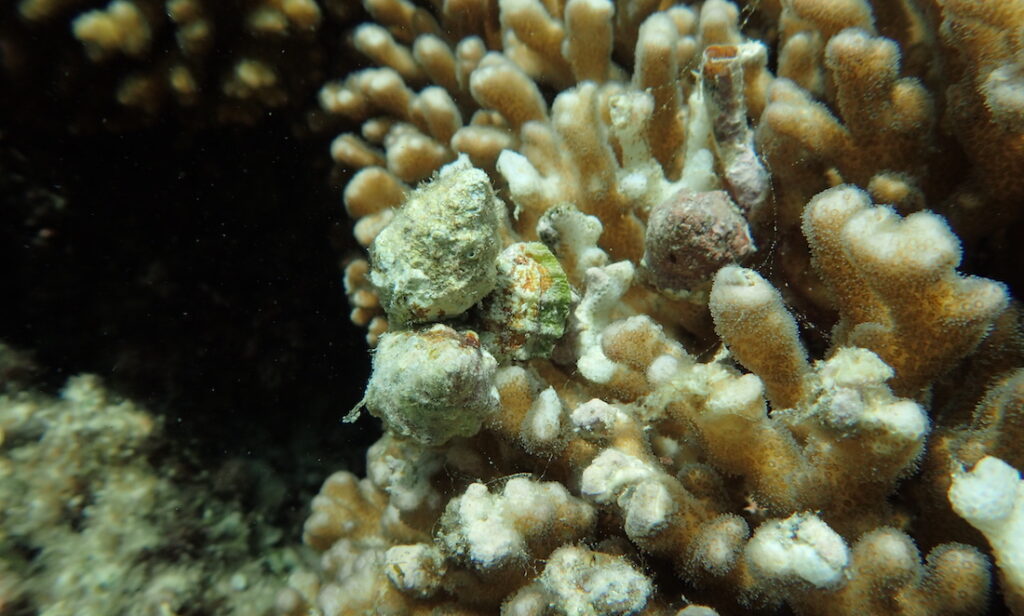

“They’re very cryptic,” she says. “They’ve got a lot of [algae] growing on their shells, so they are hard to see.”

“They hide in the branches of corals or underneath coral.”

Sometimes they can be found just hiding in small crevices in the sand.

The tiny sea snails typically grow up to 4.5cm long and loves munching on fast-growing corals found in shallow waters off Rottnest Island.

An early warning

A few years ago, Veera’s research led to the second recorded observation of Drupella at Rottnest.

However, in recent months, Veera is starting to spot more and more of the species around Rottnest.

“I was at Parker Point this Saturday and I did encounter multiple, multiple juveniles,” says Veera. “It does seem like the numbers have increased.”

Veera stresses that the snails belong to the reef and are not currently in outbreak numbers. But she says the juveniles could be a warning sign.

A familiar story

Previous Drupella outbreaks – such as at Ningaloo Reef in the early 1990s – started with large numbers of young snails. The Ningaloo outbreak reduced coral cover on parts of the reef by more than 75%.

“In the 1990s, they reckon the outbreak started with larger numbers of juveniles that suddenly were able to establish and settle and start feeding,” says Veera.

“And we have been seeing larger numbers of juveniles [at Rottnest]. Where that leads … we’re just going to have to wait and see. We don’t know yet.”

Veera’s also unsure if there are natural predators that would reduce Drupella numbers.

“We don’t know what predators would be able to consume them,” she says.

Tipping point: unknown

Murdoch University marine biologist Dr Mike van Keulen says one of the problems with Drupella is their very heavy shell.

“It’s quite difficult for regular predators to feed on,” he says. “You need particularly heavy-duty fish to be able to tackle them. So that becomes a problem in terms of keeping them in check.”

Mike says it’s still unknown what caused Drupella to reach plague proportions at Ningaloo or why their numbers returned to normal without intervention.

“They’re obviously a natural part of the ecosystem, but we don’t know what triggers them to get out of control,” he says. “I think that’s what we need to focus on.”

The other unknown is climate change.

“Particularly for Rottnest, which is at the receiving end of stronger tropical currents,” says Mike.

“It’s important to keep an eye on it because things can change quite rapidly.”

Veera says Drupella are very good at feeding on stressed coral.

“They love stressed coral – that’s their main food,” she says.

“With climate change and [storms], we get more and more stressed coral, which makes it a lot easier for Drupella to feed.”

So far, it seems Veera’s monthly scuba dives will be needed for a long time yet to keep a watchful eye on Rotto’s coral reefs and unravel some of the mysteries of this cryptic sea snail.