Australia’s 40,000-year-old cold case.

A long, long time ago, marsupials the size of small trucks, 2 metre tall ‘thunder birds’ and 5 metre long venomous lizards roamed Australia.

These animals – and more – were Australia’s megafauna.

Megafauna have always existed in Australia. But around 2.5 million years ago, they became enormous.

The largest of these animals existed during a period of time known as the Pleistocene epoch.

These Pleistocene megafauna became extinct between 60,000 and 20,000 years ago.

Hundreds of megafauna fossils have been discovered over the past decade.

Scientists are unearthing growing evidence to answer the question how did these mega beasts die out?

A SLOW DEMISE

There’s one thing researchers agree on – these massive animals did not die in a massacre type event. It was a very slow demise over 10,000 years or so.

However, this is where much of the agreement ends. There are three main theories about how the megafauna extinction occurred.

One theory is that climate change is to blame, another that humans hunted them to death and another that climate change and humans played a role.

THE HUNT IS ON

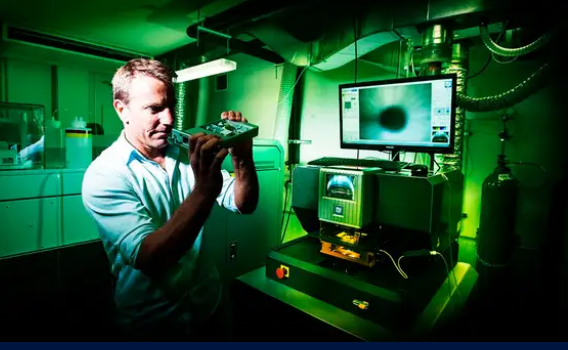

Dr Aaron Camens is a palaeontology lecturer at Flinders University.

He has studied megafauna for 20 years and believes humans played a primary role in their extinction.

“It seems ridiculous to think that, if there were large, slow-moving sources of protein wandering around, humans wouldn’t have hunted them,” says Aaron.

Credit: Supplied: Aaron Camens

“It’s not like people went and vindictively killed every single animal that they came across … but they disturbed an equilibrium.”

Megafauna were very slow at reproducing. They were in balance with the environment, but when humans arrived, this balance changed. This could make them vulnerable to extinction.

If First Nations people hunted one juvenile Diprotodon per year in a small area, this could cause their extinction across 1000 to 10,000 years, Aaron says.

“It’s [an] almost imperceptible decline across a human lifetime,” says Aaron.

CLIMATE KILLINGS?

Anthony Dosseto is a geochemistry professor who dates megafauna fossils to determine their age.

Anthony says humans and climate may have contributed to the megafauna’s demise.

“I’m sure humans played a role,” says Anthony.

“But I’m personally not convinced that there’s evidence that we should exclude climatic and environmental change.”

Anthony dated some fossils from South Walker Creek, inland from Mackay in Queensland.

The research paper dated fossils from 34,000 to 40,000 years ago.

The same team found and dated megafauna kangaroo fossils, which were only 20,000 years old. This was confirmed independently by another lab.

This date ago aligns with the last glacial maximum – the most recent time period when ice sheets were at their largest.

This young fossil provides evidence of climate playing a part in the megafauna extinction.

“It’s kind of weird because everybody is supposed to have kicked the bucket,” says Anthony. “[This finding] is going to rub a few people the wrong way.”

He believes climate and humans contributed.

“They don’t need to be mutually exclusive.”

MEGA DEATHS

Dr Kenny Travouillon is the Curator of Mammals at the Western Australian Museum.

“I feel like there’s not enough data yet to say it’s one or the other, and the reality is probably a mix of both,” says Kenny.

But he says this isn’t the case for every megafauna species.

Some megafauna, like the giant, horned turtle-type creature Ninjemys oweni, died out before humans arrived in Australia.

Kenny has found megafauna fossils, including Diprotodon, that have been dated to 100,000 years old at sites including Du Boulay Creek in the Pilbara.

Credit: Supplied: Kenny Travouillon

“[That’s] way too early for humans,” says Kenny.

Kenny believes that a few years of drought could ‘knock out’ some individuals in a population. Eventually, populations would become so small that a species could die out.

“It doesn’t mean that humans didn’t have a play,” says Kenny. “There’s at least 20 megafauna that could have overlapped with humans.”

IT’S IN THE BONES

WA is an expansive state and has diverse environments from the top to the bottom. This creates a few challenges for the megafauna fossil record.

“You can’t take one spot in WA and say it’s the same everywhere,” says Kenny.

“It’s not fair to extrapolate to the whole continent … because we don’t have the data to do that.”

“The tropics [are] terrible for our fossil record because bones don’t preserve well,” says Aaron.

“It’s not that the megafauna weren’t there, it’s just that we don’t know what was there and when they went extinct.”

Unlike the tropical regions, the southwest region has an excellent fossil record.

Credit: Vlad Konstaninov, Andrey Atuchin, Scott Hocknull and Ryan Bargial. Courtesy of Queensland Museum

UP FOR DEBATE

The southwest has such excellent megafauna fossil records that a 2010 research paper declared that caves in the area provided solid evidence that humans were to blame for megafauna extinction.

“That is a super-important site for understanding continent-wide extinction of megafauna because it shows us that these species are resilient to changes in climate,” says Aaron.

“From the records in South West WA, there seems to be a fairly strong indicator that climate wasn’t playing a large role in the extinction.

“It’s more likely to have been [a] human-driven factor.”

Kenny begs to differ.

Tyler Faith, Kenny and colleagues re-analysed the data from the study and found the climate was changing at that time too.

So the debate rages on.

THE JURY IS OUT

If the megafauna murder case went to trial today, the jury would have insufficient evidence.

So what evidence do we need to close a 40,000-year-old cold case?

Aaron and Kenny agree on this: butchery sites.

“In other continents, there’s evidence of humans butchering animals,” says Kenny.

“In Australia, we have none, like zero, not even one.”

If there’s no record of humans hunting these animals, it’s difficult to prove they were involved.

Kenny says undiscovered butchery sites may exist.

“We may find [butchery sites] in the future,” he says.

“If we found a butchery site in one area, that doesn’t mean megafauna are being butchered in all areas,” says Aaron.

“We need multiple sites from multiple different locations, different climate zones [and] different vegetation types.”

So, while this mystery is ancient, it may be early days yet.