You’re far north of Perth, deep into the rich and iron-red Pilbara. It’s hot. It’s dry.

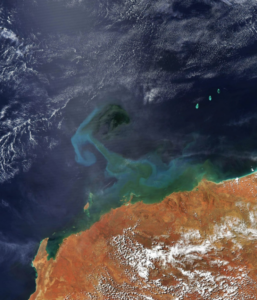

Just east of the town of Newman, you’ll find a tiny 10km × 10km area that is home to a peculiar phenomenon: extremely ordered round patches of bare soil surrounded by grass. They are known as “fairy circles”.

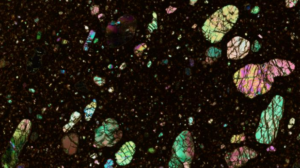

Fairy circles near Newman, WA | Dr Stephan Getzin

Where did this bizarre pattern come from? Is it a side-effect of mining? Insects? Extraterrestrials? (Fairies?)

Before you answer, consider that these aren’t the only fairy circles. No, you won’t find them on the other side of Newman. But you will find them on the other side of the world in Namibia, more than 10,000km away.

So how do identical ecological phenomena occur on opposite sides of the planet? Scientists have been asking themselves the exact same question. Dr Stephan Getzin from the University of Göttingen, Germany, has been working with scientists from the University of Western Australia to find out how these identical patterns occur in different places.

“The fairy circles in Western Australia and Namibia are identical in terms of distribution and spatial patterns,” says Stephan.

Yet there is much about their environments that differs.

“The soil composition in the Pilbara is different to the soil in Namibia, and there are different plant species covering the surrounding soil,” says Stephan.

“Rainfall also interacts with the plant life in a different way. In Australia, the soil composition makes rainwater flow overland. In Namibia, rainwater flows underneath the soil.”

If there are different environmental factors, why are the patterns identical? Some ecologists considered termite or ant activity as the answer. But while termites are more common at the Namibia site, numerous excavations at the Pilbara site revealed that termites or their nests are uncommon in those Australian fairy circles.

To understand the mystery of fairy circles, Stephan and his team needed to think bigger than termites. They needed to think bigger than just ecology. They needed to think physics.

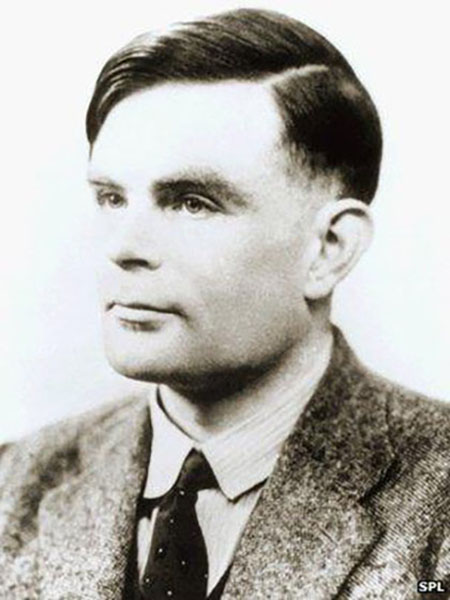

“The existence of fairy circles can be explained by Alan Turing’s theory of pattern formation theory,” Stephan explains.

“The theory says it doesn’t matter what system you have, if the system is disturbed by the right conditions, then you’ll get identical patterns.”

According to Stephan, there are examples of this all around us.

“This theory explains patterns in nature like cloud formations, sand ripples under the ocean or the way trees can grow in linear bands on a hill. Identical patterns can form in different systems.”

In the case of the fairy circles, even though so much is different, there are four key conditions that produce these identical patterns.

“Fairy circles form only in grasslands that are composed of one or two grass species, but not more.”

“You need the right plant architecture that fits the soil type. The grasses in the Newman fairy circles are highly plastic, which means they respond to water and can take on any shape or form.”

“You need the perfect amount of rainfall. Too much rainfall would destroy the fairy circles and create a uniform vegetation layer.”

“Lastly, the habitat needs to be flat.”

No wonder the fairy circles are found in such a tiny 100km2 area. To put this in context, consider that the entire Pilbara region is more than 500,000km2.

This line of thought is new in ecological thinking. But by adapting it, Stephan and his team are sure to unlock the mysteries of many more ecological phenomena in the future.