The delicate mouse is a species of native rodent that’s widespread across northern Australia.

Or at least it was.

No, no, don’t worry, it hasn’t been wiped out by some calamitous disease or misguided bulldozer. Scientists have recently discovered that the delicate mice across Australia are actually three different species!

The delicate mouse species has now been split into the northern delicate mouse (Pseudomys delicatulus), the western delicate mouse (Pseudomys pilbarensis) and the eastern delicate mouse (Pseudomys mimulus).

OK, and …?

Like, yay for science, we have two new species, but why does that matter? And how did those researchers decide they were separate species in the first place?

WHAT MAKES A SPECIES?

There are lots of ways that one species can become two along the branches of the evolutionary tree. Most often, speciation (the development of new species) is cause by geographic isolation.

When different groups of the same species are physically separated by things like mountain ranges, oceans or deserts, it stops the different groups from breeding with one another.

At first, they’re still considered the same species. But after generations of separation, unique mutations start to appear in each group that don’t get shared between other groups.

Maybe one group develops a longer nose or another group becomes more heat tolerant.

Or maybe one group starts speaking with cool new slang and making jokes the others don’t understand. No, scratch that one. That’s just how it feels talking to people from Melbourne.

Anyway, eventually enough mutations have occurred that the groups might become quite genetically and physically different to one another.

But the real clincher that splits one species into two is when different groups can no longer have viable (will survive) and fertile (can have babies) offspring with one another.

This is what we think happened to the delicate mouse, with groups separated by the enormous expanses of Australia’s interior, and why scientists decided to split them into three species.

CATEGORY IS: TAXONOMY

The study’s lead researcher, Dr Emily Roycroft from Australian National University, explains what led to their decision.

“The three delicate mouse species are genetically distinct from each other. This probably prevents them from interbreeding. Along with subtle morphological differences, this led us to conclude they were different species,” says Emily.

That might sound a bit complicated, but genetics often plays a role when scientists make taxonomic decisions.

Taxonomy is the science of naming and categorising different organisms (not to be confused with taxidermy, the stuffing and mounting of those organisms). There’s no single reason why taxonomic categories get changed, but increasingly, genetic analysis is being used to pick apart the evolutionary tree. New genetic technologies and techniques can show us how evolution has separated different species or how they may be closer than we thought.

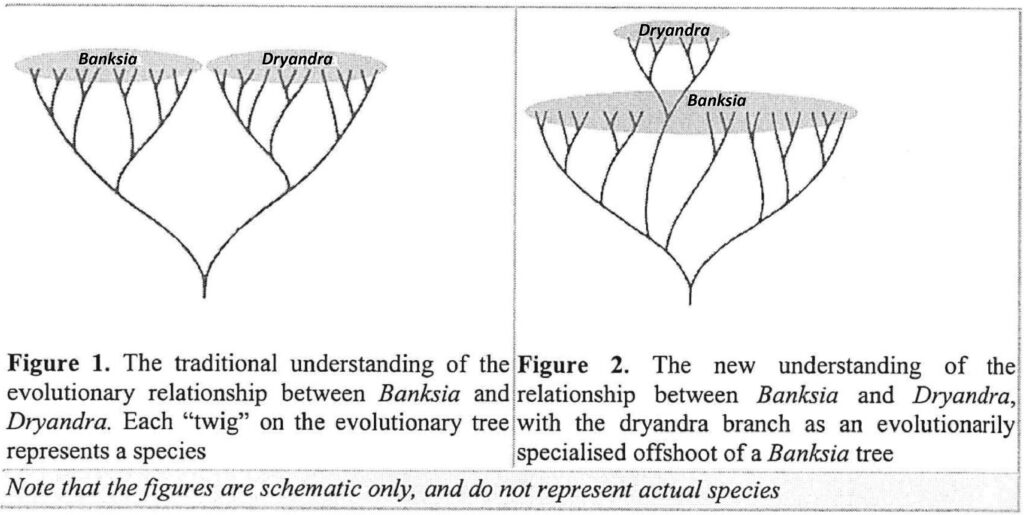

This happened in WA in 2007, when a genetic analysis showed that the plant genus Dryandra was actually just a branch of the genus Banksia rather than a genus in its own right.

Scientists made the decision to merge Dryandra into Banksia, but many frustrated hobby gardeners were left wondering why it was necessary.

Was it just scientific pedantry?

We might know how these decisions are made, but why bother changing things at all? What difference does it make?

WHY SPECIES MATTER

Scientists like Emily believe that understanding how species are related or separated is a vital part of understanding what action we should be taking for their conservation and protection.

“Like many native rodents, the delicate mice play a crucial role in their environment as ecosystem engineers,” says Emily.

Ecosystem engineers are species that alter or regulate their environment through their behaviour. In the case of the delicate mouse, its feeding and burrowing habits turn over soils and distribute seeds, ensuring the continued growth and health of their ecosystems. But living across such a huge area of northern Australia, delicate mice interact with many different environments and ecosystems.

“The three delicate mice are more specialised to their environments than we previously thought. They’re adapted to their unique habitats across Australia’s north,” says Emily.

But because the delicate mice across Australia had always been considered as the same species, very little work had been done to understand the conservation needs of individual specialised groups.

“Species most often can’t be monitored and protected until they are given formal scientific names. By giving these species their own names, we’re taking the first step towards ensuring they’re given the right conservation attention,” says Emily.

Conservation ecologists can do a better job of protecting each mouse species, and the ecosystems they support, by catering to that species’ specific needs rather than treating them all the same.

Maybe the northern delicate mouse is more affected by land clearing? Maybe the western delicate mouse has more pressure from feral cats? Maybe the eastern delicate mouse is actually endangered but we never realised because it wasn’t its own species?

Whatever the case, identifying, categorising and understanding the diversity of nature is the foundation of protecting it and ensuring that Australia’s environment remains healthy and thriving.