When flowering plants appeared in the fossil records, Charles Darwin called it an “abominable mystery”.

The plant group’s rapid diversification during the mid-Cretaceous period had the evolutionary biologist stumped.

Known as angiosperms, flowering plants now make up the majority of land vegetation on Earth.

After millions of years of plants without blossoms, how did flowering and fruiting ones become dominant so quickly?

A team of UWA scientists examined this puzzle during a recent study.

Their findings could lead to a greater understanding of early plant evolution.

pollen power

Dr Daniel Peyrot is a lecturer at UWA’s School of Earth Sciences and the study’s co-author.

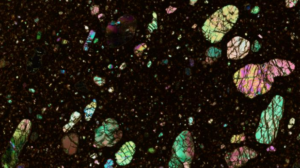

He says palynology – the study of pollen and spores – is an important field for understanding plant evolution.

“The oldest records known of flowering plants come from pollen,” says Daniel.

Fossilised pollen reveals that flowering plants first appeared approximately 135 million years ago.

The oldest records come from the Middle East, particularly in the area known as the Levant and Saudi Arabia.

“It’s an area that hasn’t been studied as much from an academic point of view,” Daniel says.

“Nothing had been done so far on the rise of diversity of this group [of plants] in this critical area.”

seeds of doubt

Lead author and PhD candidate Hani Boukhamsin says mounting evidence shows early plants colonised a variety of habitats, from forests to freshwater bodies.

“The sudden burst of different growth forms and species has puzzled palaeontologists for decades,” he says.

Daniel says scientists aren’t certain which group of plants angiosperms evolved from. Some palaeobotanists think they may have derived from seed ferns.

“These were a group of plants with leaves that look like ferns but they produced seeds,” he says.

Dinosaur dispersal

The team proposed two models to explain the sudden expansion of flowering plants.

The models combine observations of high speciation rates in modern islands with knowledge of historical landscape changes.

Most notable were huge sea-level fluctuations.

“During high sea levels, oceanic islands are … effectively isolated,” says Victorien Paumard, co-author and UWA research fellow.

“[This] transforms them into a centre of speciation.”

According to one model, flying reptiles and birds would have carried seeds to the islands on their feet or in their stomachs.

Could the pterodactyl be responsible? | Getty Images

Without connections to the mainland, gene flow between the plant populations become restricted.

The isolated plants undergo mutations and create new species on the islands.

sea change

The second model focuses on the formation of isolated wetlands and lakes when sea levels dropped.

“[These became] centres of speciation for aquatic plants and plants related to water-logged environments,” says Victorien.

Like land islands, ‘wet islands’ encouraged new species to form. Once reconnected to the mainland, the new species could spread.

Continuous rising and falling of sea levels was thought to create an ongoing system of speciation and dispersal.

the right place at the right time

The team is working on validating the models using different time intervals.

“We are going to reach that [validation] very soon,” says Daniel.

“The island hypothesis is … well-studied for modern flora. But, as far as I know, palaeontologists haven’t applied it to ancient flora.

“I believe we were in the right spot, studying the right interval of time.”

Insights into angiosperm evolution could help scientists with conservation efforts, crop production and climate change resilience.

It’s an area of research that’s bound to bear fruit.