The British Indian Ocean Territory Marine Reserve (BMR) was established in 2010 and covers 640,000 square kilometres between Tanzania and Indonesia in the central Indian Ocean. This marine reserve is 800 times bigger than New York City and the largest of its kind.

The remote archipelago is one of the best places on the planet to study reef ecosystems because fishing is banned.

UWA marine biologists Jessica Meeuwig and David Tickler and colleagues from the Zoological Society of London are studying different types of sharks in the reserve.

They are calling for more ‘marine wilderness’ areas to protect shark populations.

WHY ARE SHARKS IMPORTANT?

“Sharks are important for reef ecosystems because they keep the rest of the food chain in balance,” David says.

“Reef systems are a complex interlocking web of predator and prey relationships,” he says.

“Disturbing one element of that system has knock-on effects throughout the reef.”

If you take away sharks, larger fish increase and eat fish that eat algae, which keep the reef healthy.

APEX PREDATORS UNDER THREAT

Demand for shark meat and fins and sharks’ slow reproductive rates are factors of dramatic global declines.

“Grey reef and silvertip sharks only produce seven to 10 pups every 2 years, which for marine life is incredibly slow,” David says.

Setting aside large, totally protected areas could help rebuild their populations.

David says Australia’s most iconic protected area—the Great Barrier Reef—is actually zoned into much smaller areas with very different levels of protection for sharks.

HERE FISHY, FISHY, FISHY

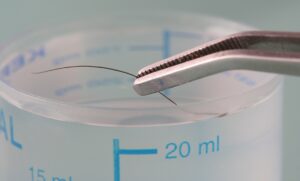

The researchers used baited remote underwater video systems (BRUVS) to survey sharks and fish at 35 sites in 2012.

BRUVS consist of two GoPro cameras attached to a frame to mimic what our eyes see underwater. They are often used in underwater research, including the artificial reef surveys in WA.

The expedition was the first BRUVS survey of the reserve and collected valuable baseline data, David says.

They counted 22,583 fish from 292 species and 271 sharks from eight species during 138 hours of footage.

SHARKS FORAGE FOR FOOD

Tawny nurse, whitetip reef, blacktip reef, grey reef, silvertip, scalloped hammerhead and great hammerhead sharks forage to find fish.

“It sounds like a bit of a no-brainer, but prey is really important to these animals,” David says.

“Because they’re large, mobile predators, they’re not tied to the reef for shelter.”

David says food availability could be more important than habitat for shark conservation.

“PROTECT SHARKS LIKE WE PROTECT LIONS”

“Marine wilderness areas encompassing reef ecosystems may conserve sharks better than protecting individual species,” David says.

“We need to start thinking about protecting big marine predators in the same way we have gone about protecting big predators on land,” he says.

“You don’t protect lion populations by declaring lions off limits but hunting everything else, because it obviously isn’t going to work.

“We set aside large areas of wilderness so they can operate at an ecosystem scale.”

“If you don’t have wilderness areas, predatory species are going to struggle.”

UWA co-author Professor Jessica Meeuwig agrees. “Like the predators of the African plains, sharks dominate the marine ecosystems of the ‘Blue Serengeti’, providing valuable ecosystem services as well as direct benefits to industries such as dive tourism. Fully protected marine reserves are a vital tool to help rebuild their populations,” she says.