The sex life of one of WA’s most iconic marine species is under the spotlight in a new study of the mating behaviour of blue-ringed octopuses.

The researchers watched the animals mating in the lab and worked out which male octopuses were successful in passing on their genes.

They discovered that longer sex isn’t better for male octopuses wanting to become fathers.

What does matter is whether the male or female ends the encounter.

They also found that the species’ unusual sperm storage strategy could be a way to avoid inbreeding.

A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO OCTOPUS SEX

First, a few things you need to know about octopus sex.

When octopuses mate, one of the eight arms on the male octopus acts as a penis and is inserted into the female’s mantle.

Female octopuses are able to store sperm packets from multiple matings.

They use sperm from different males to fertilise a single clutch of eggs.

But how this works is largely a mystery.

Some scientists believe sperm competition is behind which male octopuses get to pass on their genes.

Others have suggested some form of cryptic female choice is at play, with the mother determining which male octopuses father her babies.

CUE THE SEXY MUSIC

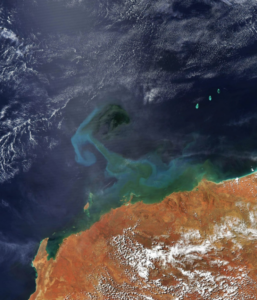

In the latest study, scientists collected 36 wild blue-ringed octopuses from Cockburn Sound and paired them in the lab.

They recorded whether the female was receptive to the male’s advances, how long the mating lasted and which gender ended the encounter.

(Yes, this means someone has a job timing octopus sex.)

They waited for the females to release their eggs and then used genomic fingerprinting to work out which male octopuses fathered the offspring in the clutch.

WHO’S YOUR DADDY

James Cook University’s Professor Kyall Zenger says all the female octopuses in the study released eggs fathered by more than one male.

It is the first time advanced genetic techniques have been used to demonstrate multiple paternity in blue-ringed octopuses.

Kyall says having sex for longer was not linked to male octopuses fathering more offspring.

“What might be happening is that the male might be what’s called mate guarding,” he says.

“So it might be just trying to hang on long enough to ensure that no other males come along.”

Male octopuses who waited for the female to end the encounter appeared to father more offspring, although the exact biological cause is unclear.

Having sex for longer was not linked to male octopuses fathering more offspring.

Kyall says the study found no signatures of female sperm selection.

But there was one male who fathered fewer offspring than expected.

When the researchers ran genetic tests, they discovered the male octopus was the brother of the female it had mated with.

“This may be a unique behavioural mechanism … to avoid inbreeding,” he says.

The work was conducted as part of the PhD research of Dr Peter Morse from the Australian Institute of Marine Science and James Cook University.