Mosquitofish. They are small, pretty, perfect for aquaria – and they’re an invasive alien species in Australia. Just like the cane toad, they were introduced to eat pesky insects, and instead they tried to take over the natural wildlife through competition and predation.

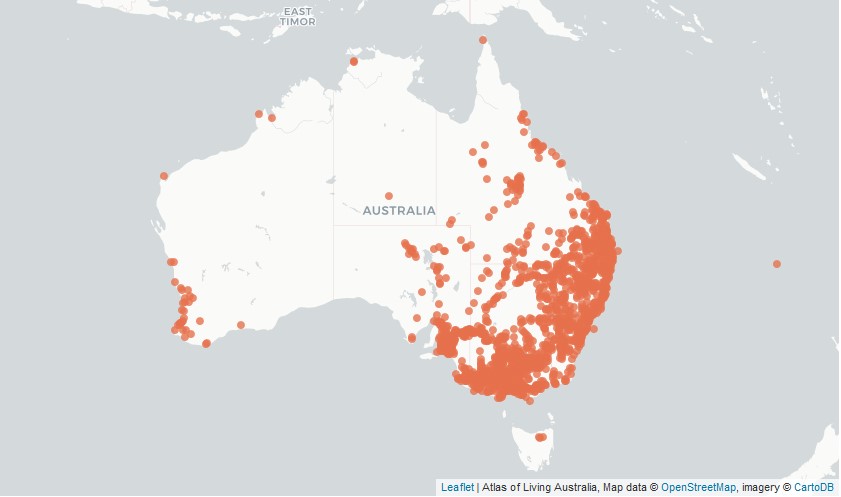

Australia isn’t unique in its story. In fact, mosquitofish are so amazing at invading ecosystems that they have been listed in the world’s 100 worst invasive alien species by the IUCN.

How to fight an alien invasion

Dr Giovanni Polverino from UWA and collaborators at New York University, Professor Maurizio Porfiri and his lab, are working to understand these alien species and how we could possibly combat them.

“It doesn’t matter where you put it, this animal can make it and survive, and adjust to the new environmental conditions,” says Giovanni.

“It’s incredible, they naturally occur in freshwater, but they can also thrive in salt water where very few freshwater species can survive.”

They are also very tolerant to different temperatures, and their eggs hatch inside their parent. ‘Giving birth’ to live young is unusual in fish – and it making them stronger and less susceptible to predation as eggs.

You have to give it to them, they are a pretty amazing species, able to survive just about anywhere. But with this comes huge impacts on biodiversity as they compete with native species.

“Humans have a strong impact on the world, and the spread of invasive species is our fault. They are animals that have been introduced by humans, into places where they don’t belong.”

“And the thing is, if we don’t reverse or attenuate the issue, things are not going to get better.”

Here in Western Australia, mosquitofish have been moving into areas of high biodiversity with unique species. Giovanni believes it is important to do something about this invasion before it is too late, and we lose important native species.

“If they are lost here, we can’t just go somewhere else in the world and bring them back.”

So what can we do?

Mosquitofish do have a natural predator, the largemouth bass – another fish on the worst invasive alien species list. Hopefully we’ve learnt enough from the cane toad story not to try and release another predator.

Chemicals like fish toxicants, or trapping them need lots of human time and effort to make it successful, and it can also have a detrimental effect on the native species.

So could scaring it into submission work instead?

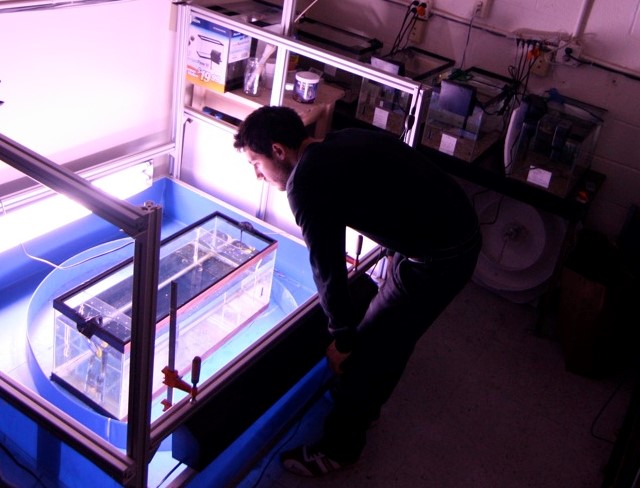

Porfiri’s team at New York University has been working with Giovanni to create a robot that looks, and moves like the largemouth bass, which could scare the mosquitofish so much that it changes its behaviour.

When the robot is around, it scares the mosquitofish. The fish uses up energy trying to protect itself, and seems to have less success reproducing.

Just like any other scientific experiment, the robot fish has evolved over time.

“We had no idea how to make a robot interact with live fish, so we started very, very basic, with something that looked like a fish, that we thought was moving like a fish – but that was with our eyes not with the eye of a fish!” Giovanni says.

They had to understand what the fish liked, didn’t like, and work on the robot until it became an effective robot predator.

So just how does the robot work?

“The robot alters the behaviour of the fish, but also the fish has an influence on the robot – they do interact with each other in real time. When the fish is close to the robot, the robot will attack and the fish will swim away. We are studying the mathematics of this interaction to understand the underlying relationship.”

The team found that just 15 minutes of exposure to the robot largemouth bass per week had longer term effects on energy levels and body condition. The mathematical models also helped the team to understand the movement patterns that the robot should take to scare the invasive mosquitofish the most.

At the moment, these studies have been within tanks in controlled environments. Before the robots head out to help fight the aliens, there are a few more questions that need to be answered.

What are the long term impacts of the robot on the mosquitofish? How many of these predator robots are needed, and could they also affect the native species?

Giovanni and the team are working on finding answers already – and before we know it, robot fish could be part of helping humans reverse our mistakes. Aliens versus robots: the saga continues – and we know which one we’d rather win.