What happens when a creative evolutionary biologist stumbles upon the famous works of an eccentric writer? A theory that’s so controversial it spurs debate and research to this day.

In 1973, Leigh Van Valen was analysing fossil records when he noticed something that didn’t make sense. Species were consistently becoming extinct without any changes occurring in their environment.

Sure, extinctions happen when an asteroid hits, a flood wipes out a landscape or a lake dries up. But why would a species go extinct when the environment is still perfect for them?

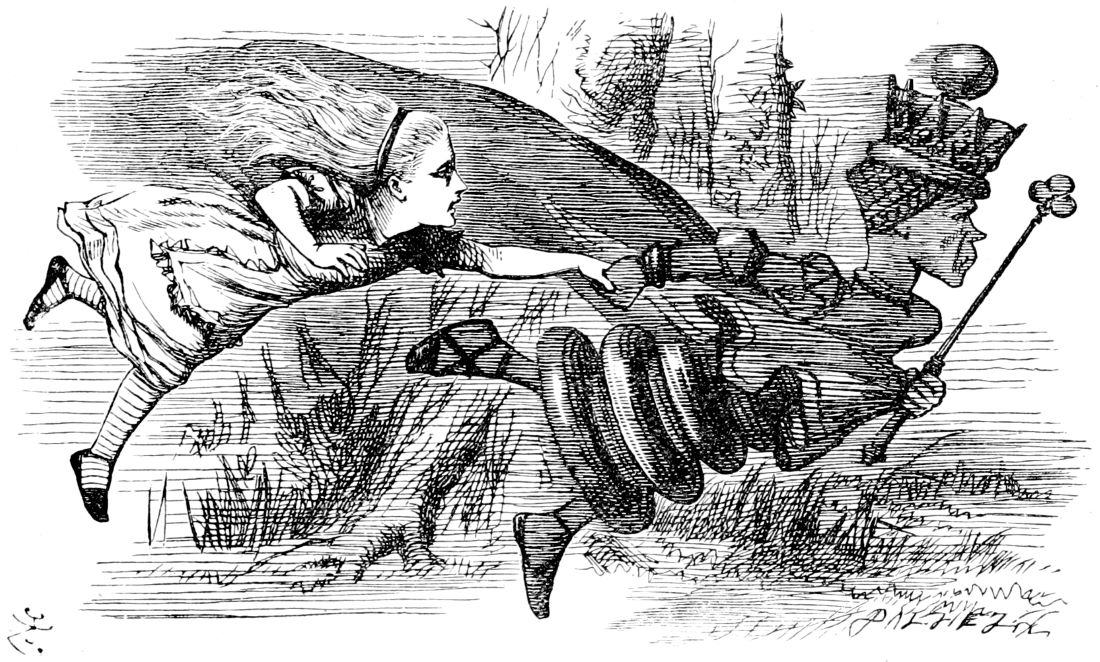

Perhaps Van Valen was reading Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll to his kids. Maybe he remembered a book report from back when he was a schoolboy. Or maybe a colleague just suggested a clever name.

In any case, Van Valen’s analysis led him to propose the idea of an evolutionary race where an organism must constantly mutate and adapt just to keep up with its competitors. And he called it the Red Queen hypothesis, a reference to Lewis Carroll’s Red Queen who says:

“Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that.”

The Red Queen hypothesis suggests that, when species evolve new traits, they gain an advantage over their competitors. The competitors then evolve and bring things back to a level playing field. And on and on the race goes until a species fails to evolve fast enough and becomes extinct.

You can see it in action everywhere including right here in WA.

The kangaroo and the pea plant

Across Australia, for millions of years, kangaroos have eaten a variety of native plants.

Some WA pea species like Gastrolobium evolved to have a toxin called fluoroacetate (aka the 1080 poison) to deter herbivores.

In response, the kangaroos developed an immunity to the toxin and kept on eating the plant.

So in another attempt to deter herbivores, some pea species started growing spikes or spines on their leaves.

Unfortunately for them, the kangaroos did not care and found a way to keep on eating them.

Running, running and running, just to stay in the same place.

Controversy

Now, the Red Queen’s reign over evolution hasn’t been without its challenges. Critics have suggested that it oversimplifies complex phenomena and fails to consider the multitude of factors that drive evolution.

However, it’s unlikely that Van Valen, who died in 2010, would have minded the criticism. As he once said:

“I am a generalist and tend to open new approaches more than fill them in.”

And the Red Queen hypothesis certainly did that. Despite its criticism, Leigh Van Valen’s idea has inspired decades of research and remains one of the most influential evolutionary theories in history.

A thought-provoking view on life itself.