Sixty metres underground in the Goldfields, hidden aquifers support small subterranean ecosystems. The creatures that dwell here are true troglofauna. They’re blind burrowing insects, fungi and small lifeforms who haven’t seen light for generations.

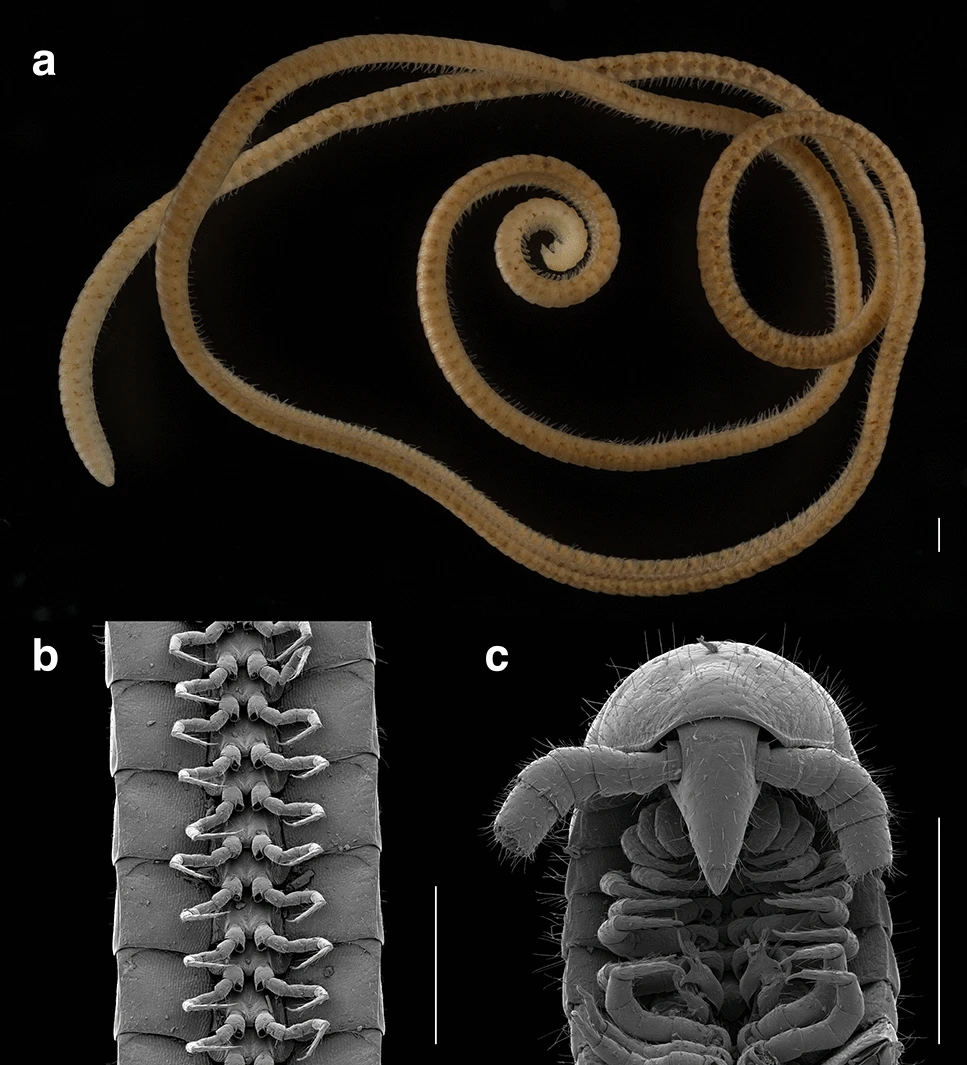

During an ecological survey in 2020, biologist Dr Bruno Buzatto bored deep into the ground and left traps of rotting leaves. When he returned, he made an incredible discovery – a new species of millipede.

Although the name ‘millipede’ comes from the Latin for ‘1000 feet’, this was the first true millipede known to science. The largest female had 1306 legs, making it the leggiest animal on the planet. It was named Eumillipes persephone, after the Greek goddess of the underworld.

An offshoot on the tree of life

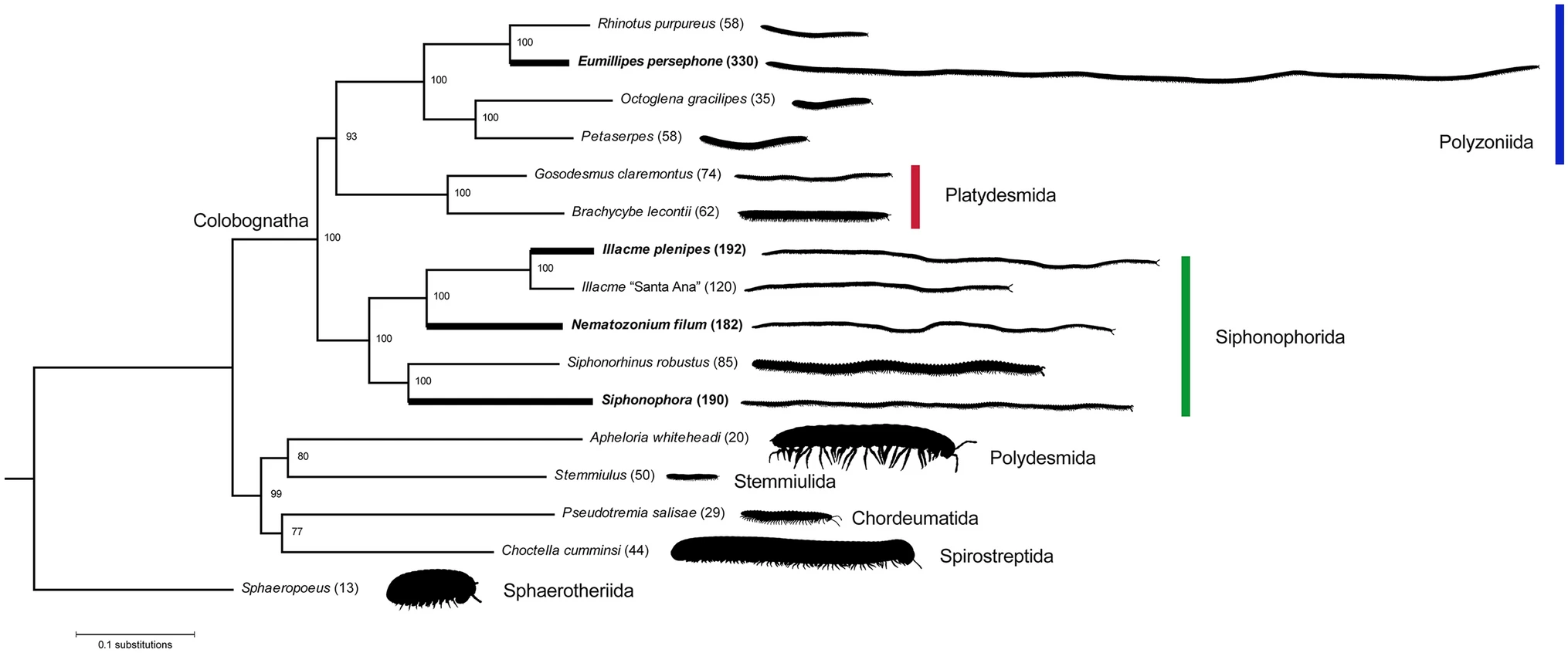

Dr Juanita Rodriguez was part of the team that catalogued the millipede’s discovery. She was responsible for building a tree of life that shows how E. persephone relates to other millipedes.

“Eumillipes is a new genus based on this discovery. However, it is a sister of Rhinotus [a much smaller millipede native to the Caribbean]," says Juanita.

And it’s not WA’s only record-setting species. The world’s longest animal lives off the Kimberley coast. The siphonophore is a 50-metre floating colony of zooids. These small animals grow together into a huge predatory net, catching small crustaceans.

Pushing the limits

So what are the limits of biology? All life on Earth exists because of chemical reactions. Our shared evolutionary history means these chemical reactions tend to be similar across domains of life.

Almost all life requires some form of respiration or fermentation for energy. The physical laws of these reactions form limits on life.

For example, an insect’s exoskeleton limits its size. An exoskeleton is expensive to maintain and must be shed each time the insect grows. Meanwhile, it has less energy because of its lack of internal organs.

Recent genetic analysis of two millipede genomes (not Eumillipes) revealed that the species has undergone a series of unique adaptations over time.

A leg up

E. persephone uses its many legs to propel itself forward. Its long form enables it to snake around impassable rocks, but each leg requires energy and systems of internal support like muscles and control networks.

“This adaptation seems to help navigating very intricate, small crevices and moving in different planes,” says Juanita.

Some biologists hypothesise that, beyond a certain size, the cost of moving an exoskeleton becomes greater than the force more muscle provides. E. persephone’s slender frame may keep its mass low enough for its telescoping legs to exert more force.

“Growing longer but not wider may keep the mass low, but then there are structural problems,” says Juanita. “How do you keep your body’s integrity when you’re so skinny? Its exoskeleton may be harder than other millipedes’ [to maintain its body integrity].”

Its blindness – ideal for crawling around in the dark – may reduce the amount of energy spent on its senses, freeing up more energy for growth.

While there are many unanswered questions about the limits of biology, WA’s extreme landscapes and isolation make it one of the most dynamic places on the planet for unique lifeforms to thrive.