When people are irresistibly drawn to something, they’re said to be like a moth to a flame. Whether it’s an idea, a person or a packet of Tim Tams, when you just can’t help but be pulled in, you become the proverbial moth.

But why are moths so enamoured with flames to start with?

I CAN’T HELP IT, IT’S SO BEAUTIFUL

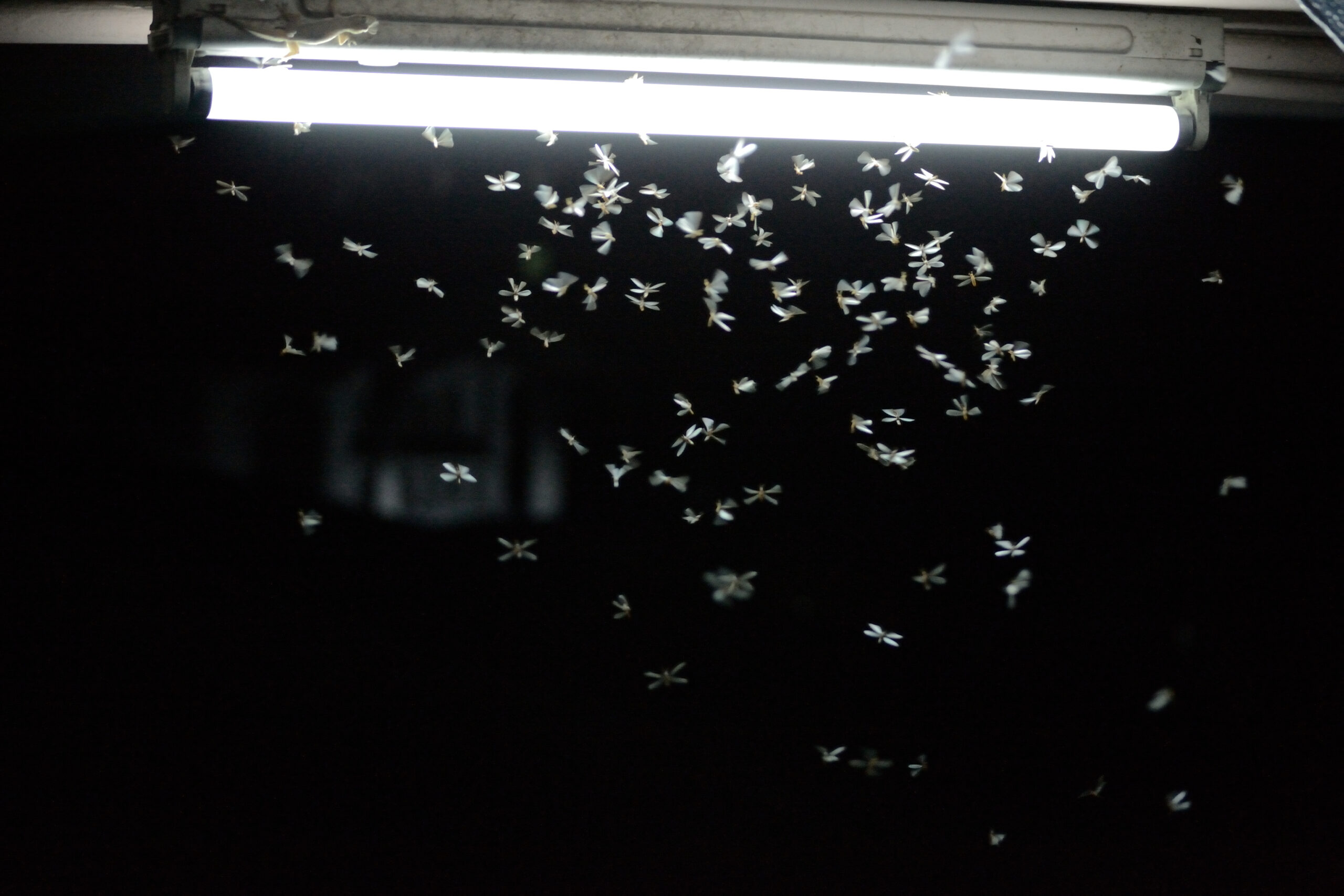

Most of us have probably had our peaceful nights disturbed by the sound of moths manically flying into our porch lights or windows. So despite the popular phrase, it seems that moths are not exclusively attracted to flames but artificial lights as well.

But somehow ‘like a moth to an LED’ just doesn’t sound as poetic.

GIPHY

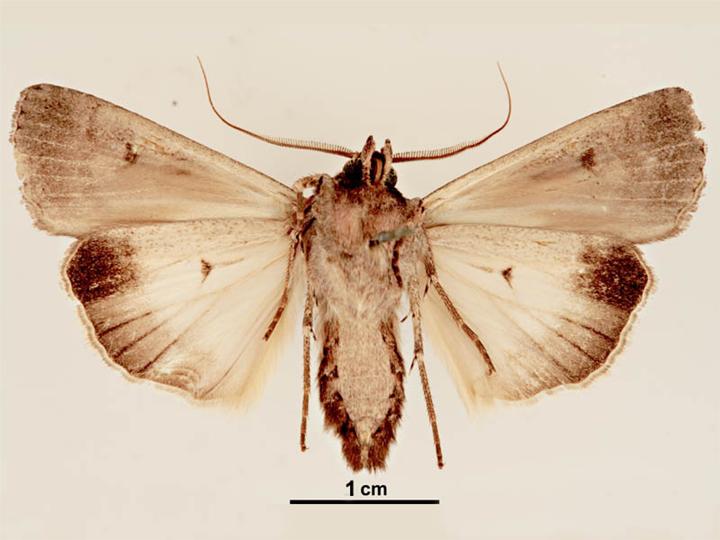

Perhaps the most famous example of this phenomenon in Australia is the case of the iconic bogong moth.

During their annual alpine migration over Canberra, the native species have a tendency to get very distracted by the lights of Parliament House.

Since the lights were first turned on in 1988, the moths have swarmed the building whenever unfavourable winds steer them off their natural route, which unfortunately proves fatal for many a misguided moth. It’s even prompted the Australian Department of Parliamentary Services to create an official policy to deal with the aerial insect invaders.

But why are they attracted to the lights in the first place?

It might seem like a simple question, but there are several theories that try to explain this moth mystery.

MOON-MAD MOTHS

One of the most common explanations relates to moths orienting their flight path using the Moon.

The Moon is so far away that its position relative to the moth’s body doesn’t change as it flies. So moths can maintain a straight course of flight by keeping the Moon on one side of their bodies. Unfortunately, this logic doesn’t quite work when it comes to artificial lights.

If a moth mistakes an artificial light source for the Moon, then by trying to keep the ‘Moon’ consistently on one side, it ends up spiralling around and around the light.

But according to Australian entomologist (insect expert) Professor Eric Warrant from Lund University, whose research focuses on bogong moths, the idea of lunar navigation isn’t backed up by evidence.

“It’s pure speculation and has never been shown. A more plausible hypothesis is that, like all insects, moths have what’s called a dorsal light response,” says Eric.

“Since the sky is always brighter and more ultraviolet rich than the ground, the sky is a very good indicator of the upward direction. So by orienting their body so that the brightest part of the world is seen directly above, a moth can maintain a horizontal body position.”

Similar to the lunar navigation theory, this explains why moths and other flying insects would continuously spiral around a flame as they try to keep the lightest part of their vision above them.

A COLOURFUL WORLD AT NIGHT

Despite that, even more theories suggest that moths are attracted to artificial lights because of their extraordinary vision.

“Moths have amazing nocturnal vision. Some even see colours at night, unlike us,” says Eric.

Some researchers have proposed that artificial lights give off the same ultraviolet light as the flowers they pollinate, fooling the moths into thinking they’re food.

A study conducted in 1977 (which has received little support) even suggested that artificial light sources might mimic the infrared light that female moth pheromones give off.

It doesn’t take much to poke holes in these theories. Even simple questions make them seem dubious. For example, do only male moths circle lights? Or do moths only circle lights that produce UV?

This may be part of the reason why Eric is more convinced by the evidence-backed dorsal light response hypothesis.

But despite the evidence to support it, at this stage, there’s still no way to know for certain why moths are attracted to flames. If only we could ask a moth!

Sandy Smith New Beginnings 66 | Pinterest

THE IMPACTS OF MOTH CONFUSION

What we do know is that the attraction moths’ (along with other species) have to artificial light can be harmful to the ecosystems they’re a part of.

“Artificial lights can seriously disrupt their nocturnal flight behaviour and negatively impact their ability to pollinate flowers at night. They are major pollinators of nocturnally flowering plants and are also an important food source for many night-active animals,” says Eric.

So when we use the phrase ‘like a moth to a flame’ to describe our own irresistible attractions (which sometimes does involve a literal flame), it’s worth sparing a thought for what that really means.

We’ve dramatically changed the night sky so that it is now full of light. As a consequence, species like the bogong moth that have always lived in the dark are being led astray. For the sake of this iconic Australian species and thousands of others like it, maybe it’s worth letting the night sky be a little bit darker.

Interested in learning more about fire and its impact on the people and environment of Western Australia? Tune into the second season of the Elements podcast.

Across five episodes, we cover everything from festival bonfires to devastating wildfires, from echoes of ancient knowledge to the technological possibilities of the future. It’s going to be lit🔥

All episodes out now on all your favourite podcast platforms.