Imagine you’re diving the icy depths of Antarctica. At 1000 metres below sea level, you’re enveloped in vast inky darkness. Your pressurised polar dive suit creaks under the strain of thousands of litres of water.

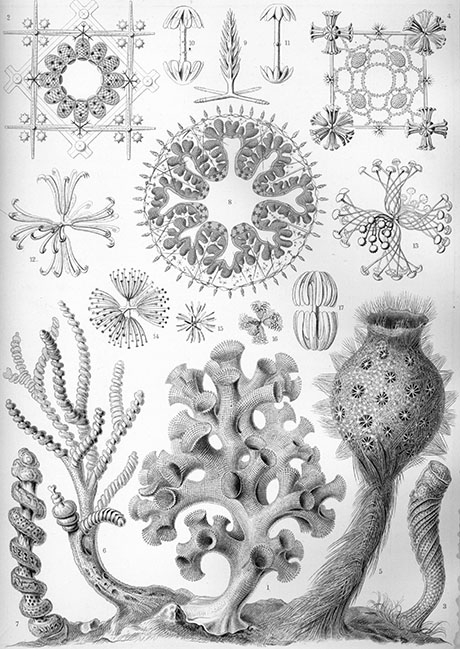

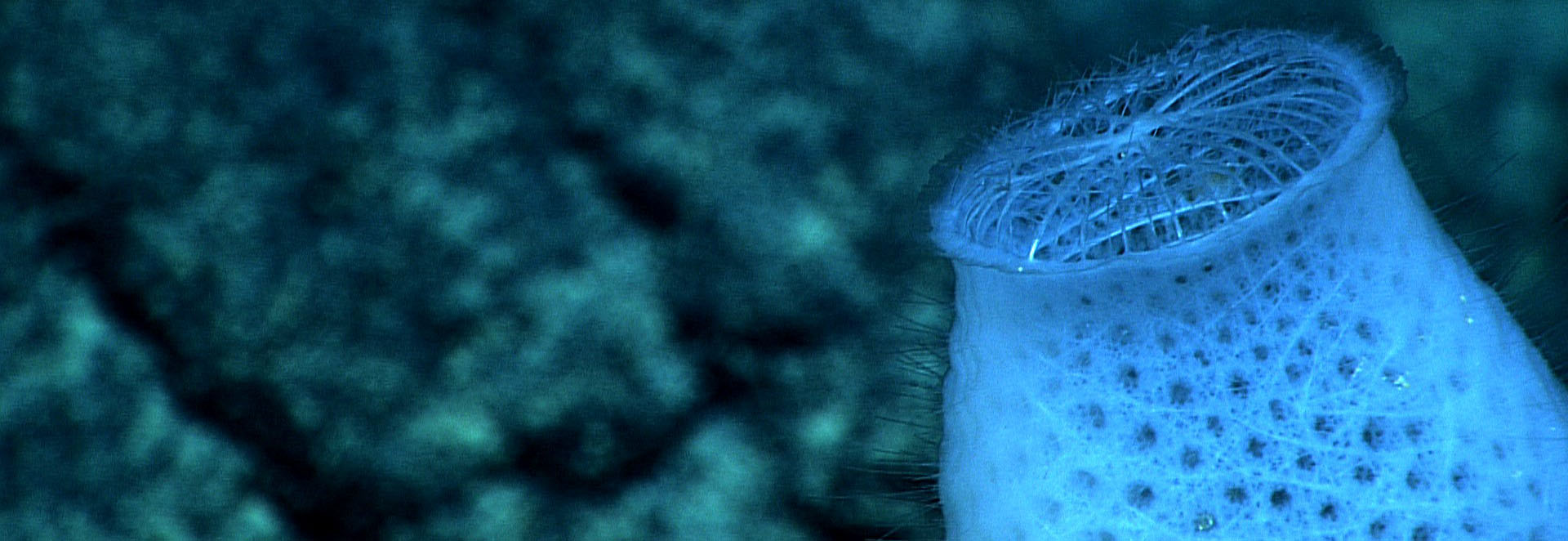

Strange creatures flit in and out of your torch beam. As you explore the seabed, you spy an intriguing shape. It’s the sea sponge Euplectella aspergillum or Venus’s flower basket.

True to its name, this deep-sea creature has a tube-shaped basket structure.

Its skeleton is made of silica – the main component of glass. The lattice-like mesh of its body filter feeds tiny food particles from the seawater.

Such a fragile “glass house” seems impossible at these crushing depths. Yet this delicate-looking sponge, only millimetres thick, is much tougher than it appears.

A high-pressure job

Dr Giovanni Polverino from The University of Western Australia’s Centre for Evolutionary Biology is part of an international team studying the remarkable properties of the Venus’s flower basket.

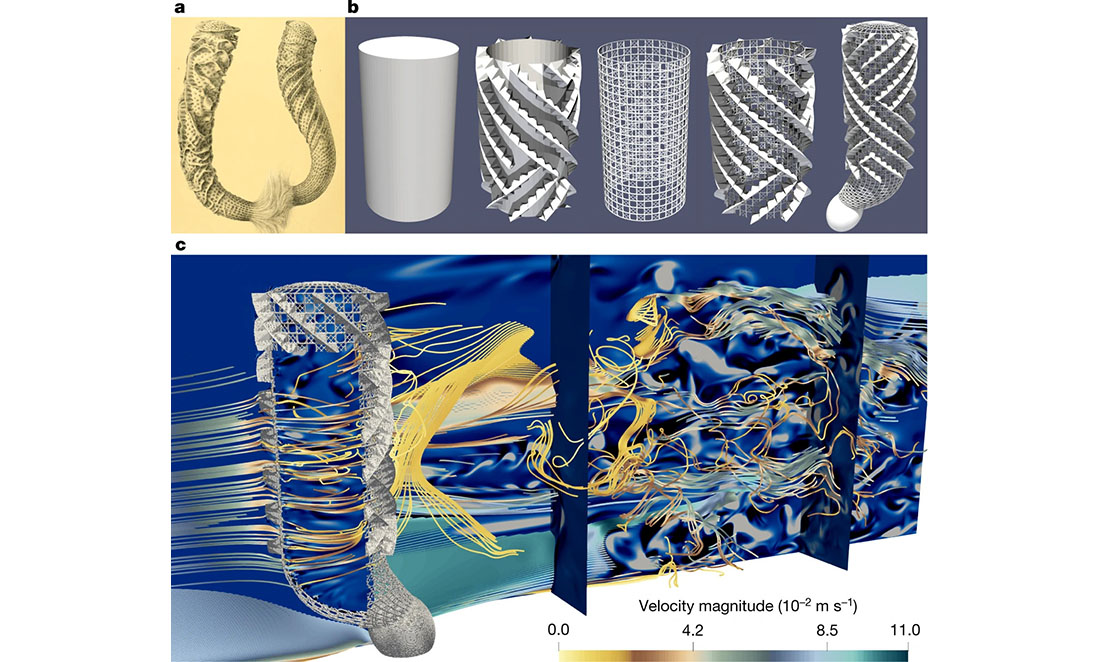

The researchers are modelling the sponge’s structure to understand how it can withstand such bone-crushing depths.

“It’s already well known that the structure is very strong,” says Giovanni. “It could inspire new materials with glass as the main element. It is human construction based on what natural selection has achieved over hundreds of thousands of years.”

Giovanni studies how the sponge’s cylindrical shape allows water to flow in and out of its body. As well as endure a high-pressure environment, the sponge needs to accommodate these currents for food and fertilisation.

“Super computer, be a sponge”

The researchers used the most powerful supercomputing centre for scientific research in Italy – Cineca.

The Marconi supercomputer ranks in the top 10 fastest supercomputers in the world. During its peak runs, it processes at a rate of roughly 1000 personal computers.

The team built a digital model that simulated the sea sponge’s structure and water flow. The giant grid held 50 billion points that reproduced how water would flow at that spot.

The digital model was created from photographs. It’s so inaccessible and rare that it would be near impossible to test real samples.

Deep-sea sponge simulation

Once they had simulated the sponge’s unique structure, the team simplified it to see how a less-evolved species might survive the current.

“It has incredible adaptions that allow it to live where no other animal lives,” says Giovanni. “We tried removing levels of complexity. We saw why this animal needed such a beautiful structure.”

Part of the sponge’s stability is its ability to go with the flow – literally. While firmly anchored to the seafloor, the flow of fluid in and out of its body reduces drag and minimises damage.

“The deep waters are very fast, so this serves to lessen the impact,” says Giovanni.

The sponge’s spirals have beautiful breaches, gaps that reduce drag and collect water for the sponge’s feeding.

“They look like decorations around the surface. Our simplification removed these breaches and found the structure’s advantages were lost.”

Inspiration for future innovation?

So could understanding the mechanical marvel of this elegant yet robust deep-sea sponge inspire future feats of engineering?

Researchers say their findings could have implications for more-advanced designs for buildings, bridges and aircraft, particularly those that need to withstand air and water pressure.

It’s putting deep-sea sponges at the intersection of fluid mechanics, organism biology and functional ecology.