Forensic entomology is the study of arthropods found in, on and around dead bodies.

Their presence, absence, bite marks, eggs, larvae, gut contents and chemical composition can all be analysed as clues.

However, arthropod behaviour is changing due to climate change, invasive species and habitat loss. And world-leading forensic entomologist Dr Paola Magni from Murdoch University says these changing dynamics will affect the future of forensic entomology.

CLUES ON THE FLY

Flies (Diptera) are usually the first creatures to find a corpse. They’re attracted to volatile molecules released by a decomposing body.

“They’re like sharks to blood,” says Paola.

Blow flies and flesh flies tend to lay their eggs on the body.

So by identifying their species and age, forensic entomologists can estimate the likely time since death. This is known as the minimum post-mortem interval (PMI).

Their location on the body can also give clues about the cause of death.

“They’re looking for easy access to internal parts of the body, where it’s humid, dark and juicy,” says Paola.

Wounds or lesions provide this kind of access, so if maggots are in weird places, it could point to foul play.

BEETLE JUICE

Beetles (Coleoptera) generally arrive at the party a bit later, either to feed on the body or hunt the flies and other insects that have already arrived.

The species of beetles found can provide further clues to the PMI.

Carrion beetles (Silphidae), larder beetles (Dermestidae) and bone beetles (Cleridae) tend to arrive in a predictable order, known as succession.

Succession is also affected by the environment such as temperature, moisture and seasonal patterns.

Depending on where the body is found – on the ground, buried, in water or in a suitcase, for instance – different successions are expected.

“Some species are location specific. They can therefore indicate whether a body has been moved from one location to another,” says Paola.

“[They] can provide insights into where death occurred and any movements.”

IMPORT-ANT CONSIDERATIONS

Ants are a less commonly studied group in forensic entomology, but their activity can add valuable pieces to the puzzle.

They’re also more likely to be misinterpreted, raising the risk of false conclusions.

Paola recently co-authored a study showing how ant activity can mimic haemorrhaging.

“It can be a potential source of confusion in forensic investigations,” says Paola.

“Ants may bite the body, causing bloody lesions, or feed on bodily fluids. This [forms] patterns or marks that resemble ante-mortem haemorrhages or bloodstains.”

Her study proposed a new classification system to help accurately identify ant bloodstain patterns.

“We can examine the patterns, locations and characteristics of the marks to determine whether they’re the result of insects or trauma,” says Paola.

A GUT FEELING

The insides of arthropods can hold clues too.

“In the insect’s gut content, we can find mixed DNA profiles. The victim’s, the suspect’s or someone potentially involved in the crime,” says Paola.

The bugs can also be tested for any drugs, toxins or poisons involved.

“Different insects react to different drugs in different ways,” says Paola.

“Analysis of their tissues or development patterns can reveal if a victim’s been exposed to these substances,” says Paola.

GROUP EFFORT

While forensic entomology usually focuses on a few main groups of arthropods, investigators can take into account any creatures that show up.

This can mean anything from mosquitoes and spiders to lobsters and barnacles, depending on where the victim is found.

GIPHY

Paola says she once tracked fireflies – which were found in a dead bear’s stomach – to discover the source of a wildlife poison.

“We followed the light of the fireflies to find poison bait residuals,” she says.

GRAVE CHANGES

Changes to the abundance, development, range and seasonal patterns of any of these creatures can have direct effects on forensic entomology.

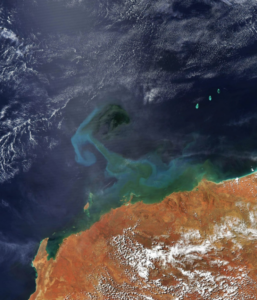

Many species are sensitive to temperature and precipitation. This means climate change can mess with the expected standards.

“[It] may lead to shifts in the timing of insect colonisation, making PMI estimation more challenging,” says Paola.

Native species are increasingly outcompeted by invasive species and displaced by habitat destruction. This impacts their diversity and behaviour at crime scenes.

According to Paola, land changes can alter the decomposition process itself, impacting the succession of insects on a body.

“Forensic entomologists in Australia will need to adapt to these changing conditions by conducting ongoing research,” she says.

“We may need to develop new models and tools to account for these shifts.”