Western Australia’s waterways are an essential part of life.

Our rivers and lakes support extraordinary biodiversity and the city’s growing population. So, maintaining their long-term health should be a top priority.

But the state of the Swan River shows we need to do a lot better.

IN AILING HEALTH

In 2014, WA’s auditor-general assessed the health of the Swan Canning River System.

It found the water quality was “in moderate to poor condition and declining”.

This was due to decades of human impact, particularly the influx of nutrients since the 1990s.

In a bid to recuperate its failing health, a plan to rebuild aquatic ecosystems that had long since disappeared was proposed.

A HISTORY OF SHELLFISHNESS

Five thousand years ago, the Swan-Canning Estuary was home to vast colonies of the Australian Flat Oyster, Ostrea angasi.

When they eventually died out, they left shell deposits which created a reef habitat that allowed other aquatic species to thrive in the area for thousands of years.

But when Europeans arrived, they dredged the Swan and harvested reef material for cement.

That practice decimated the river’s fragile ecosystems.

Dredge ‘Black Swan’ decorated, 1897 | Battye Library [230481PD]

REPLACING LOST REEFS

In 2020, The Nature Conservancy Australia (TNC) started building mussel reefs in the Swan-Canning estuary.

As natural filter feeders, the mussels would remove pollutants from the water and improve its quality.

At the same time, the reef structure would provide habitat for a wide variety of aquatic species.

Dr Alan Cottingham is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Murdoch University’s Centre for Sustainable Aquatic Ecosystems.

He’s been studying the progress of the reefs which have shown some promising results.

Constructing the new reef | Credit Michael Bond via Overland Media

The presence of shellfish have provided a variety of benefits to coastal environments.

“They provide habitat and prey communities for fish and crustaceans and enhance biodiversity,” he says.

“They also improve water quality through filter feeding.”

While it’s early days yet, Alan’s research shows what a little “mussel power” can do.

“Once fully functioning, the mussel reefs could filter about 35 percent of the entire estuary during winter," says Alan.

“So over 90 days, that would be over 40 tonnes of organic matter.”

Biodiversity returning to the mussel reefs | Scott Breschkin via The Nature Conservancy

NOT ALL SMOOTH SAILING

Most of that organic matter comes from upstream in the Swan.

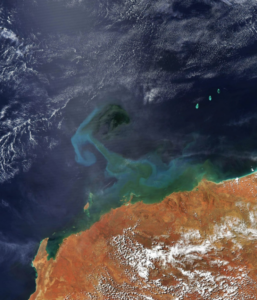

Agricultural runoff enters the river, causing algal blooms that choke the waterways.

Decreased rainfall has exacerbated the problem. Less rainwater due to a drying climate has increased the concentrations of these pollutants.

The good news is that the encouraging early findings of Alan’s research offer hope for the future of the Swan River.

A HELPING HAND

Scott Breschkin via The Nature Conservancy

TNC aim to roll out their Reef Builder initiative nationally.

Their goal is to re-establish shellfish reefs at 60 locations across Australia. Thirteen projects are already underway.

“This is a step towards our broader goal of restoring 30 percent of this lost habitat,” says Alan.

However, the issue of shellfish reef destruction extends far beyond Australia’s waters.

“Over-harvesting, disease, and declining water quality have led to the loss of around 85 percent of shellfish reefs worldwide” says Alan.

Currently, TNC is focused on achieving the best outcomes for the Australian projects. But in the long-term, they hope to demonstrate the benefits of shellfish reefs for marine ecosystems across the world.

“We are currently exploring the potential of other reef-forming shellfish to future-proof the reefs from the impacts of climate change,” says Alan.

These “future-proof” reefs may contain species adapted to the warmer conditions expected in the future.