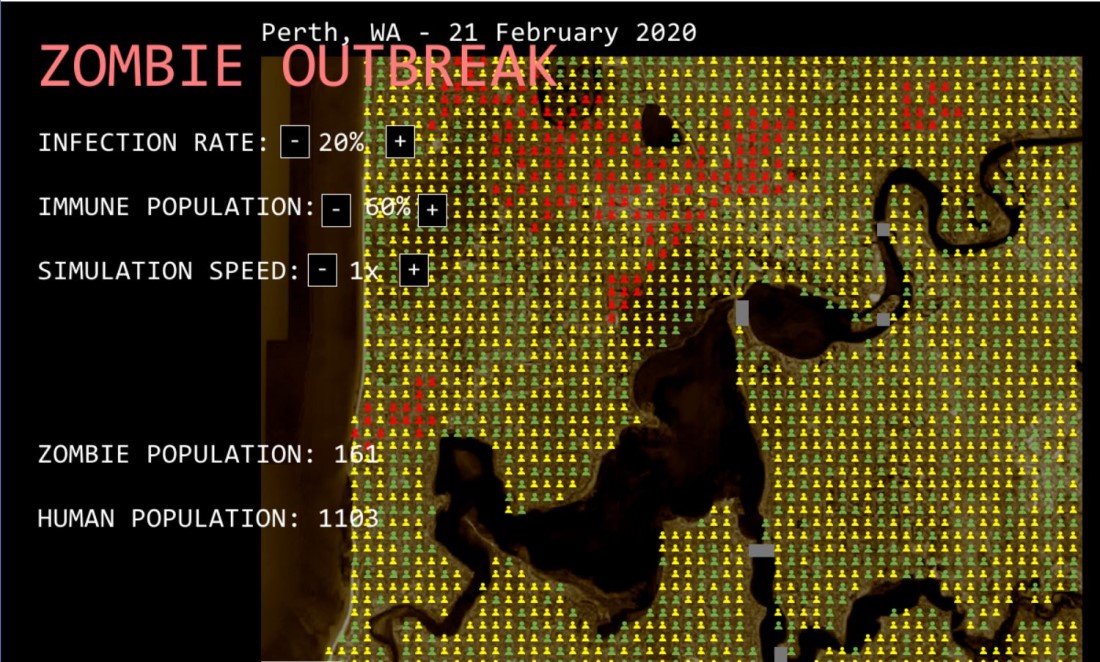

Could sandgropers be the last survivors from a zombie outbreak? Will having the Nullarbor – and Adelaide – between us and the rest of Australia’s population keep us safe?

If these kinds of questions keep you up at night, we’ve got some good news. There’s someone whose job it is to answer them.

East vs west

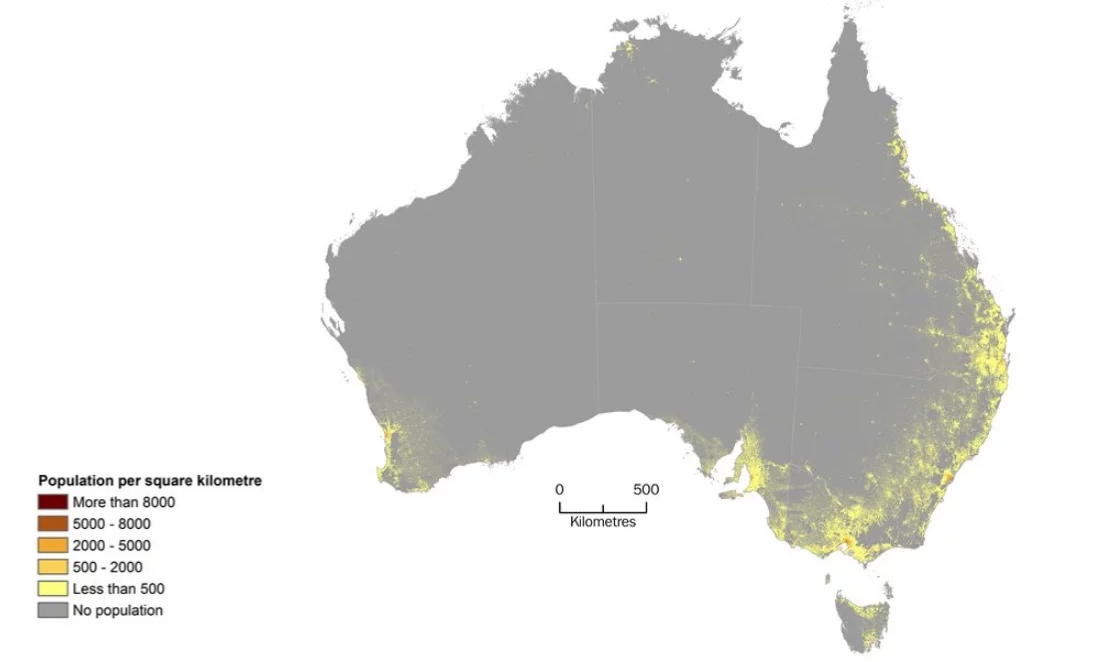

“When you look at the population density across Australia, it would get very hard to get across here,” says Dr Valerie Maxville, a Professor at Curtin University.

“Walking from Melbourne to Perth – because zombies would be walking, we don’t believe they can drive cars – would take 27 days. And the decomposition rate of bodies – because the zombies would be decomposing – is equal to 1250 over whatever the temperature is. That tells us how long until there’s nothing left but a skeleton.”

With the average temperatures in the desert, it would take somewhere between 30 and 40 days, so they could just make it, but only if they knew we were here.

“There is no incentive for them to walk across the desert. I don’t think they’d even try to walk across. All that area with almost zero population would be too much of a barrier, even from Adelaide.”

“If the zombie apocalypse starts on the east coast, Perth might just be OK. The only thing that would get them across is hitching a ride.”

North vs south

So if a zombie did catch a ride to Perth, perhaps on the last truck out of Sydney, what could we do?

“If we could figure out some way to immunise people – maybe stop the zombies being attracted to them – it would take much longer to spread. Otherwise, it’d be about isolating it,” Valerie says.

“Once the infection is in a populated area, it’s about quarantine. We’d have to stop all the traffic and cut off all the bridges to stop it spreading.”

So depending on where our first zombie arrived, whether you’re north of the river or south of the river might literally be a matter of life or death.

Don’t try this at home

Despite how it might sound, Valerie’s job isn’t about herding zombies or demolishing bridges. She’s a computer scientist, and she works with simulations.

We can’t release actual zombies – partly because they don’t exist, and partly because unleashing the zombie apocalypse just to see what happens is more than a little unethical.

That’s exactly why simulations are useful: they let us try things we can’t do or shouldn’t do in the real world.

If you’ve ever crashed a rocket in Kerbal Space Program or set a forest on fire in Minecraft just to see what would happen, you probably understand why it’s useful to do experiments in a simulation instead.

“You can play with the parameters and run lots of versions of it with different parameters to see where the issues are and what interventions could have the best outcomes.”

But just because they’re not real doesn’t mean they don’t have some basis in fact.

How to simulate a zombie apocalypse

Since zombies aren’t real, we have to base the modelling on something that is.

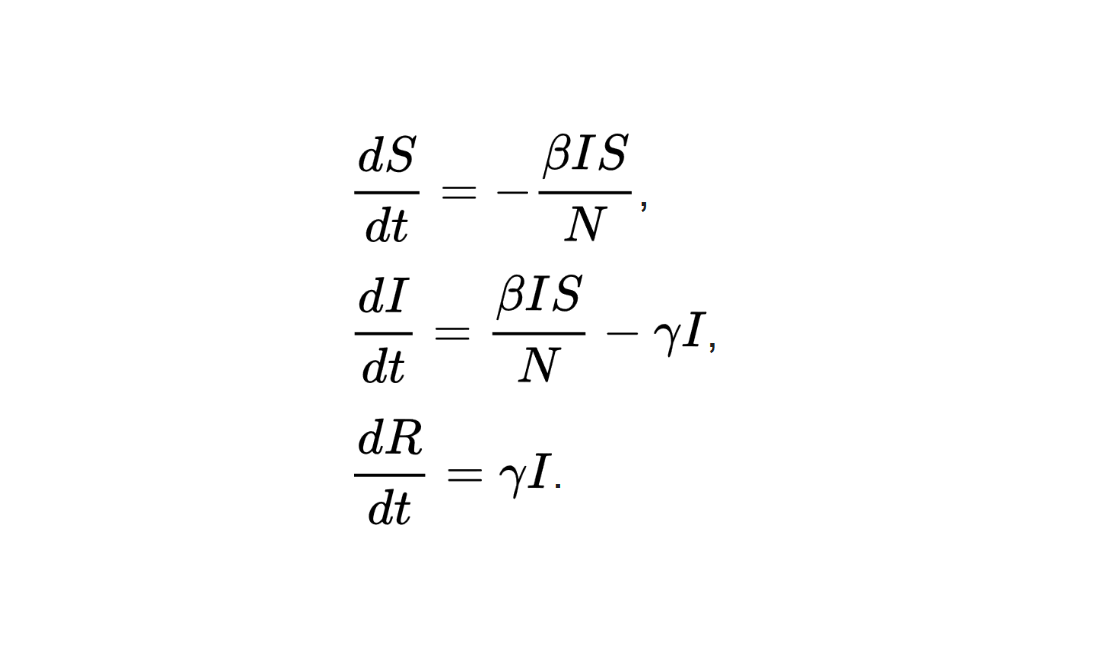

“The equations we’re looking at here actually come from epidemiology, which is the study of disease,” says Shyam Drury, our go-to maths guy at Scitech.

“It’s a simple model for contagious illness, looking at the number of not infected, the number infected and contagious and the number who are infected but not contagious any more because they’re either immune or dead.

“Although looking at it, it is three coupled non-ordinary differential equations, so maybe it’s not that simple after all,” Shyam says laughing.

Then we make some assumptions about how our zombies work. These simulations assumed they’re faster than humans, they can’t swim and they’re attracted to the sound or smell of living humans.

We take our knowledge and our assumptions and crunch them down into a simple set of mathematical rules something like this:

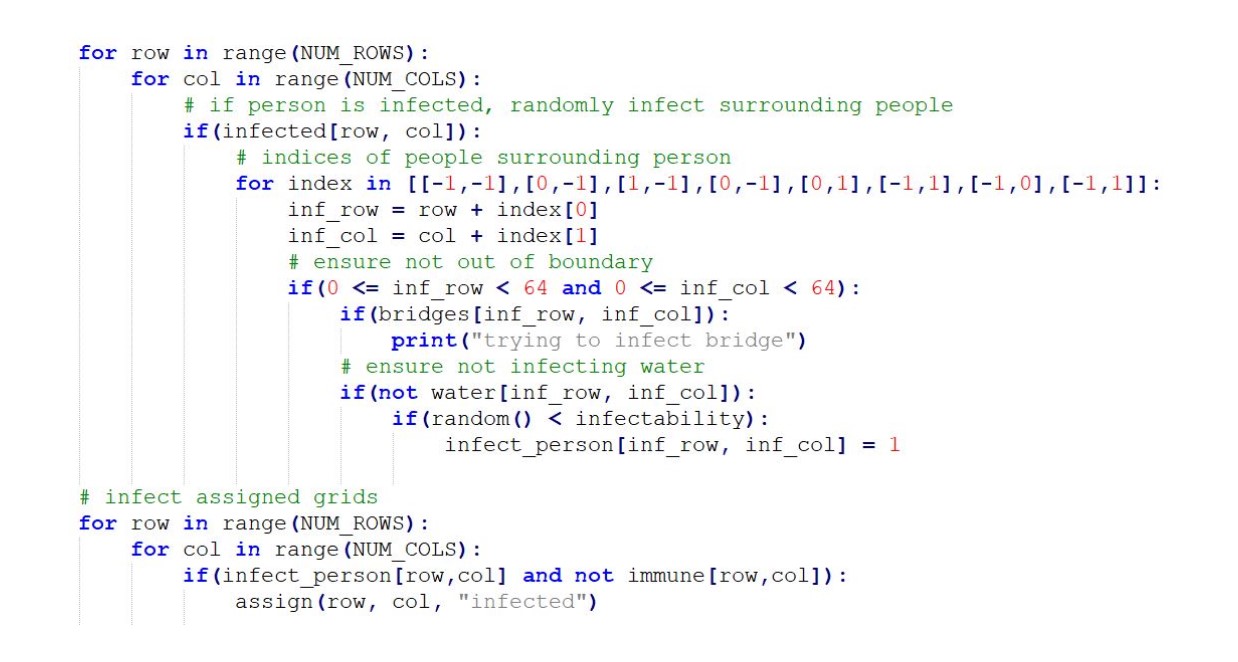

1. If there’s a zombie next to a person, they’ve got x chance of getting infected.

2. If there’s more of them, the odds of infection go up by a certain amount (y) for every zombie added (z): y x z.

3. And if they’re surrounded, infection is all but certain: when x + yz ≥ 100%

Then we line up a whole grid of “people” following those rules, drop an infected zombie down and watch how the disease spreads over and over again.

But this simulation is not perfect. We’ve assumed people don’t move, and that Perth’s population is evenly spread out. Luckily, that’s not too big of a problem.

“You set up a simulation and then you run it and then you look back at the real world and see what you got right and what you got wrong, and you keep refining it,” Valerie says.

“You’re working on a model and your model is always going to be wrong with assumptions and simplifications, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be useful.

“You can prepare for something that doesn’t exist yet or an environment that you can’t actually go in to.”

But … why?

What use is it having some idea of how a zombie apocalypse might really play out?

“I don’t really like zombie movies myself, but the concept and how it applies—with the recent measles outbreaks, for example—it’s all relevant even though it may seem quite silly,” says Valerie.

Learning to use simulations like this one can also be a great way to practise and get people interested in coding, and they can use those skills to build simulations that do matter.

“I teach first-year students who perhaps need a bit more of a hook to get into programming, and as soon as you say it’s a zombie outbreak, then it becomes a little bit more interesting to talk about.

“I’m always looking for a vehicle I can use to teach these sorts of concepts.”

Simulations are all around us, helping us predict and manage things like traffic, the climate or real diseases. If zombies can help us understand how those work a little better, then that’s a pretty useful thing.

Plus, if you ask us, it never hurts to be prepared.