One bright and sparkly morning last week, I arrived at my desk, coffee in my hand and science communication on my mind. The topic du jour? The latest research from CSIRO, which attempted to better answer the question where on Earth is MH370? I sat, ready to write a concise, compelling and factual article.

I emerged from the building many hours later, absolutely fried.

Was it the CSIRO paper that had got me in a flap? No. It was my background reading on the topic—or more precisely, the conspiracy theories that surround the mystery disappearance. There are lots of them.

So what is the science behind the search for MH370? And what does the latest science say? To get my facts straight, I spoke to Professor of Coastal Oceanography at UWA, Charitha Pattiaratchi.

LET’S TAKE IT BACK TO THE START

Seven satellite pings were the only traces left by MH370 before it disappeared on 8 March 2014.

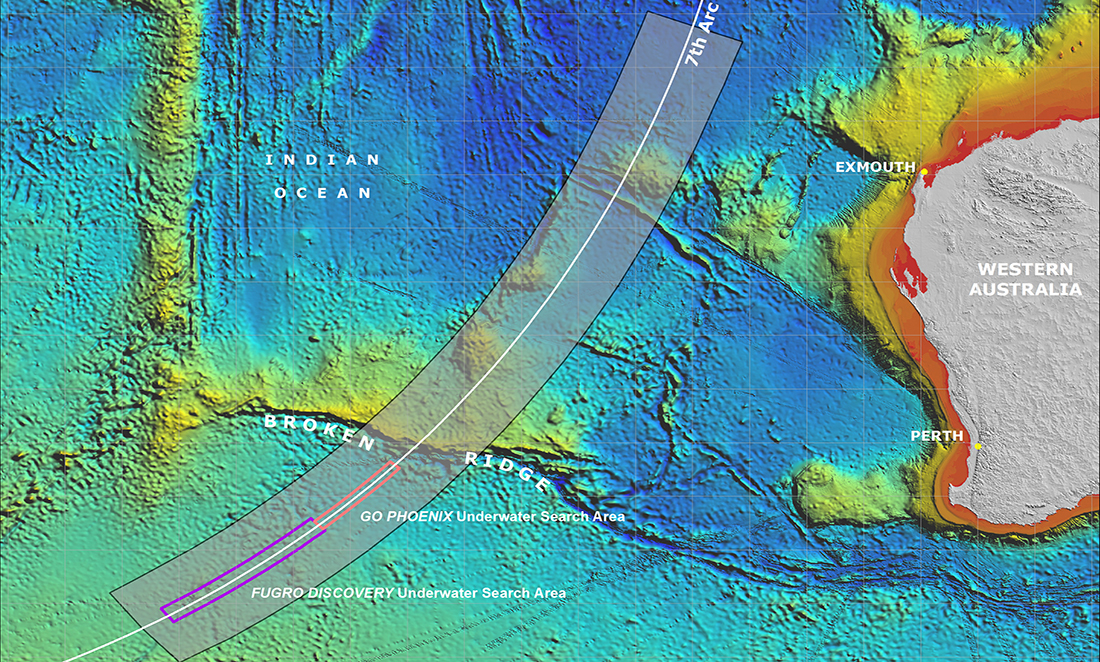

These bleeps were analysed by specialists who identified a stretch of Indian Ocean (referred to as the Seventh Arc) as the likely location of the missing Boeing 777.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB), leaders of the seafloor exploration, used this info to define the search area between 39° south to 32° south—encompassing a measly 120,000km2. That’s like looking for a plane wreck somewhere in 2182 Sydney harbours or two whole Tasmanias—except, you know, very deep under water.

The extensive (and expensive) expedition yielded no trace of the missing MH370. It mostly just spawned conspiracy theories, each more complex than the last.

Meanwhile, 16 months after the initial disappearance and 4000km from the search area, a large chunk of the plane’s wing—known as a flaperon—washed up on the shores of Réunion Island.

This fuelled the conspiracies burning hot throughout the World Wide Web. Those that believed the plane to be elsewhere (South China Sea, Kazakhstan, Diego Garcia, etc.) were quick to dismiss the flaperon as planted evidence.

But in fact there was a simple scientific explanation for the arrival of such debris.

BUOY OH BUOY

Using data on ocean surface currents collected by satellite-tracked buoys, the CSIRO analysed potential pathways plane debris could have travelled depending on the plane’s location. They concluded that finding the flaperon on Réunion Island would support the search area initially defined by the ATSB.

This is saying that the second piece of evidence found (the flaperon) supported the findings from the first piece of evidence (the satellite pings).

With only two pieces of evidence in existence at the time, that’s a 100% success rate.

Professor Pattiaratchi and his UWA team predicted this would happen, months in advance of the flaperon’s appearance. Using computer simulations, he was able to calculate the probability that debris would wash up at any one location, depending on its start point.

The UWA computer models accurately predicted the location of 18 of 22 pieces of debris. 82% is a high distinction in anyone’s books. However, when you are a piece of plastic sloshing around in the ocean, many factors will affect where you go—and computer models can’t predict them all. For instance, simulations did not account for the presence of small islands where the four other pieces of debris washed up.

To better understand what other factors might be at play, the CSIRO moved from computer modelling to real-life debris drifting.

FLAPERON FIdDLING

In early December 2016 (over a year on from the buoy trajectory tracking), the ATSB published another CSIRO study, which replicated and analysed debris drift from the MH370 wreckage.

By analysing the movement of life-size debris replicas, scientists could appreciate the effect that wind would have on objects in the ocean. This experiment helped them refine the computer model that could predict where the plane might be.

By analysing the movement of life-size debris replicas, scientists could appreciate the effect that wind would have on objects in the ocean. This experiment helped them refine the computer model that could predict where the plane might be.

Their findings suggested that the plane crashed a tantalising 1° north of the current search area.

Unfortunately, this new search site recommendation arrived too late. In January 2017, the search of the initial area was completed with no wreckage found. According to a pre-existing agreement, the search was postponed until “credible new information” comes to light.

GET REAL

Despite the official search being postponed, scientists at CSIRO would not cease or desist.

They conducted another drift analysis in April 2017. Whereas the first CSIRO drift analysis looked at how replica debris might move in the ocean, this one worked with the real thing.

After getting their hands on a genuine Boeing 777 flaperon, CSIRO scientists whipped out the power tools and did a little DIYing. Referencing photographs, they cut down the flaperon to mirror damage seen on debris that washed up on Réunion Island.

Then they popped it in the ocean and watched how its shape affected the way it drifted.

A key difference here? The replica flaperons of the first analysis were made of wood and steel, whereas the real thing is made out of composite materials—a mix of things like fibreglass, carbon fibre and plastic.

Experiments like these are used to understand how our world works. By using an authentic flaperon instead of a replica, scientists can more closely model real-life debris drift, adding validity to their findings.

So what did this study find?

Nothing new really, but that’s not to say it wasn’t useful.

It served to increase the scientists’ confidence that the plane is located at 35° south along the Seventh Arc, 1° north of the initial search area.

EYES IN THE SKIES

This brings us to the latest report from CSIRO, released in August this year. And this one is a doozy.

“We think it is possible to identify a most-likely location of the aircraft, with unprecedented precision and certainty.”

At the very beginning, satellite data pinged and pointed us towards the seventh arc.

And once again, it seems these planetoid paparazzi might unravel the MH370 mystery.

On 23 March (15 days after the plane’s disappearance), satellites snapped some pics of the sea surface about 150km to the west of the seventh arc.

Geoscience Australia analysed these images and found 70 ‘objects of interest’. Ranging from 2 to 12 metres in size, these objects were classified on a spectrum from ‘probably natural’ to those that are ‘probably man-made’, of which there were 12.

Check out the satellite images for yourself.

CSIRO asked whether the location of these objects on 23 March was consistent with MH370 hitting the water within the area that their previous reports suggested.

Short answer? Yes, it was.

Slightly longer (and more frustrating) answer? Yes, it was, if the plane went down at 35.6°S 92.8°E, a spot just north of the area we spent so long searching.

If the plane landed somewhere along the white line, could we explain debris appearing in the spot where the satellite saw them on 23 March?

Yes, if you factor in currents. Where the blue, black and red lines get distorted, the currents are strongest. Any debris swept up by them would go pretty far. Which means CSIRO can calculate the most-likely crash site to be 35.6°S 92.8°E. They do suggest other possible crash locations, both east and west of the arc.

But these conclusions all stem from one big assumption—that these objects of interest were actually ex-plane parts. Because if there’s anything that we’ve learned from the search for this plane it’s that there is a lot of random stuff out there in our oceans.

WITHIN BELIEF

As with any hotly debated and widely discussed story, theories and conspiracies abound.

Scientific models and experiments allow us to eliminate subjectivity. They discriminate between fact and fancy and allow us to perpetually evolve our understanding of the world as new evidence comes to light.

In regards to the use of drift analyses to find MH730, Professor Charitha Pattiaratchi says,

“From an oceanography point of view, there is no more compelling evidence … what more do you want?”

Whether this evidence will reignite search efforts, we can’t say. That decision rests with the powers that be.

But in the meantime, stay critical and (if you can) ask an expert.