Our electronic world is full of batteries, and WA’s renewable future may rely on them too.

And with great reliance there comes a need for great quality.

So how do we make batteries better? Researchers from the Edith Cowan University may just have the answer – in the form of a new zinc-air battery.

It’s cheap, safe and sustainable.

ZINCREDIBLE COMEBACK

Currently, lithium-ion batteries are the most common battery type powering our devices.

They took over from the older zinc batteries during the 1990s. Now, zinc’s making a comeback.

“The new generation of zinc-air batteries are secondary batteries, [also known as] rechargeable batteries,” says Dr Muhammad Rizwan Azhar, an ECU chemical engineer who was involved in the creation of the new product.

“The old generation were primary batteries. Once they depleted, you would throw them out. This is the most significant difference.”

Energy researchers are revisiting zinc batteries because they’re cheaper and less vulnerable to overheating or catching fire – a serious weakness of lithium.

“Zinc batteries can store more energy than lithium-ion,” says Muhammad.

“There are fewer safety concerns with their storage and use too.”

REDUCE, RENEW, RECHARGE

The team set out to find a zinc-air battery that could compete with the energy storage of lithium batteries.

“Australia’s well placed to produce zinc-air batteries,” says Muhammad.

“We produce 20% of the world’s zinc supply. It’s abundant and easy for us to process.”

We’re also the world’s largest lithium producer, so we’re the ideal country for battery research.

Although rechargeable batteries are significantly less wasteful to use, designing an efficient one can double the amount of chemistry involved.

There’s at least one chemical reaction that releases energy, and at least one separate reaction to store it again.

LONG-LIFE ZINC

Zinc-air batteries can store around 500 watt-hours per kilogram.

That’s nearly three times more than lithium-ion batteries and 10 times greater than lead-acid batteries.

The trade-off is that, because air isn’t a good conductor, the battery may last a long time but it won’t be able to power larger devices.

“[Manufacturers] have already trialled zinc-air batteries at full commercial scale using other materials,” says Muhammad.

“There were some issues with these batteries, which is why we’re trying to improve their performance.”

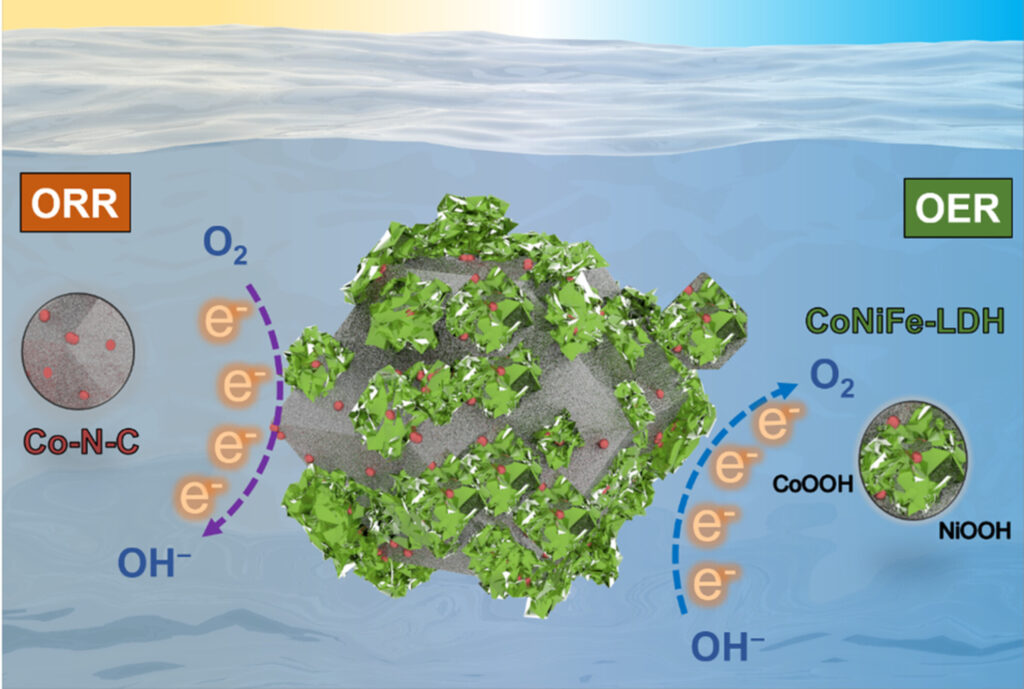

LAYERED LIKE A LAMINGTON

The team at ECU improved the battery design by combining different chemical structures. Then they applied them in layers – sort of like a lamington.

The first structure is a spongy crystal lattice of cobalt, nitrogen and carbon called ZIF-67.

The treated spongy interior is very conductive and can easily supply electrons to oxygen.

The outer crumbly layer is made of cobalt, nickel, iron and oxygen, called layered double hydroxide.

This metal coating is less conductive but can take electrons from oxygen groups.

These two structures complement each other. They allow the zinc-air battery cell to efficiently supply 1.48 volts. That’s roughly the amount of an AA or AAA battery.

HIGH VOLTAGE

Muhammad says manufacturers can link multiple battery cells to provide more voltage to devices.

We already do this with existing batteries.

By placing them positive to negative, the voltage of the batteries adds together. Larger devices need more batteries because they require a higher voltage to run.

GIPHY

Zinc is unlikely to completely remove lithium from batteries, but it could ease global demand for the metal.

“Lithium is a finite resource, and we are rapidly consuming natural deposits,” says Muhammad.

“We need to look for alternatives to lithium … We are looking for industry to apply our research to the commercial scale and become a world leader in the production of zinc-air batteries.”