The latest version of a plant identification sensor, the Photonic Weed Detection System, has been almost a decade in the making.

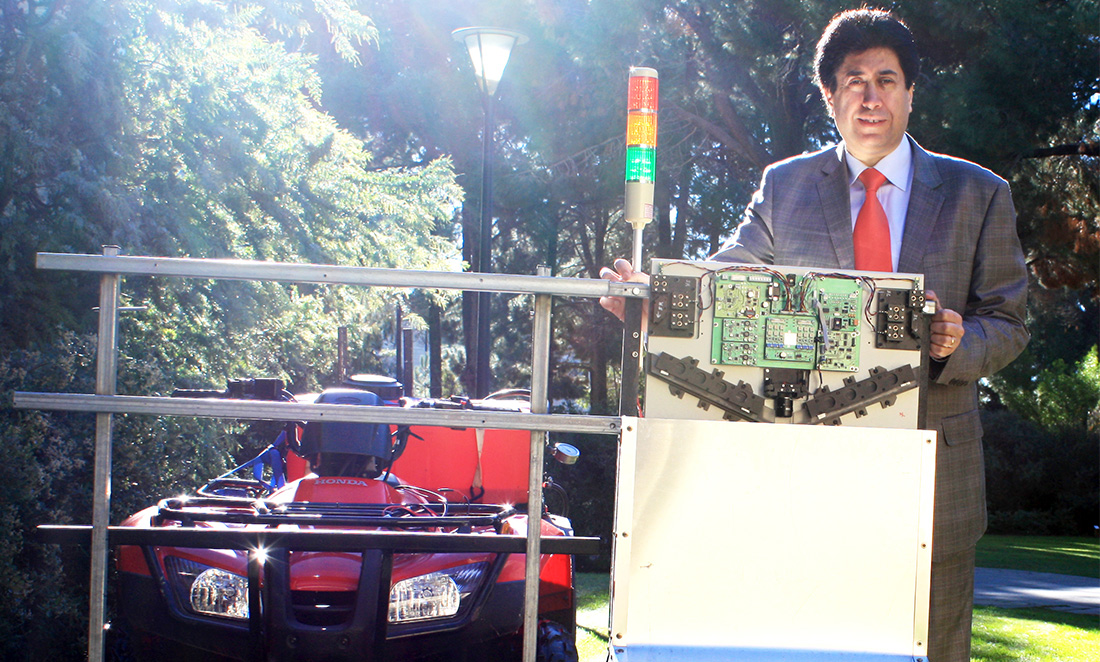

In 2007, Perth-based Photonic Detection Systems teamed up with ECU’s Electron Science Research Institute (ESRI), led by Professor Kamal Alameh, WA’s Inventor of the Year 2007.

Six years later, they showcased a plant identification sensor believed to be a world-first for green-from-green discrimination.

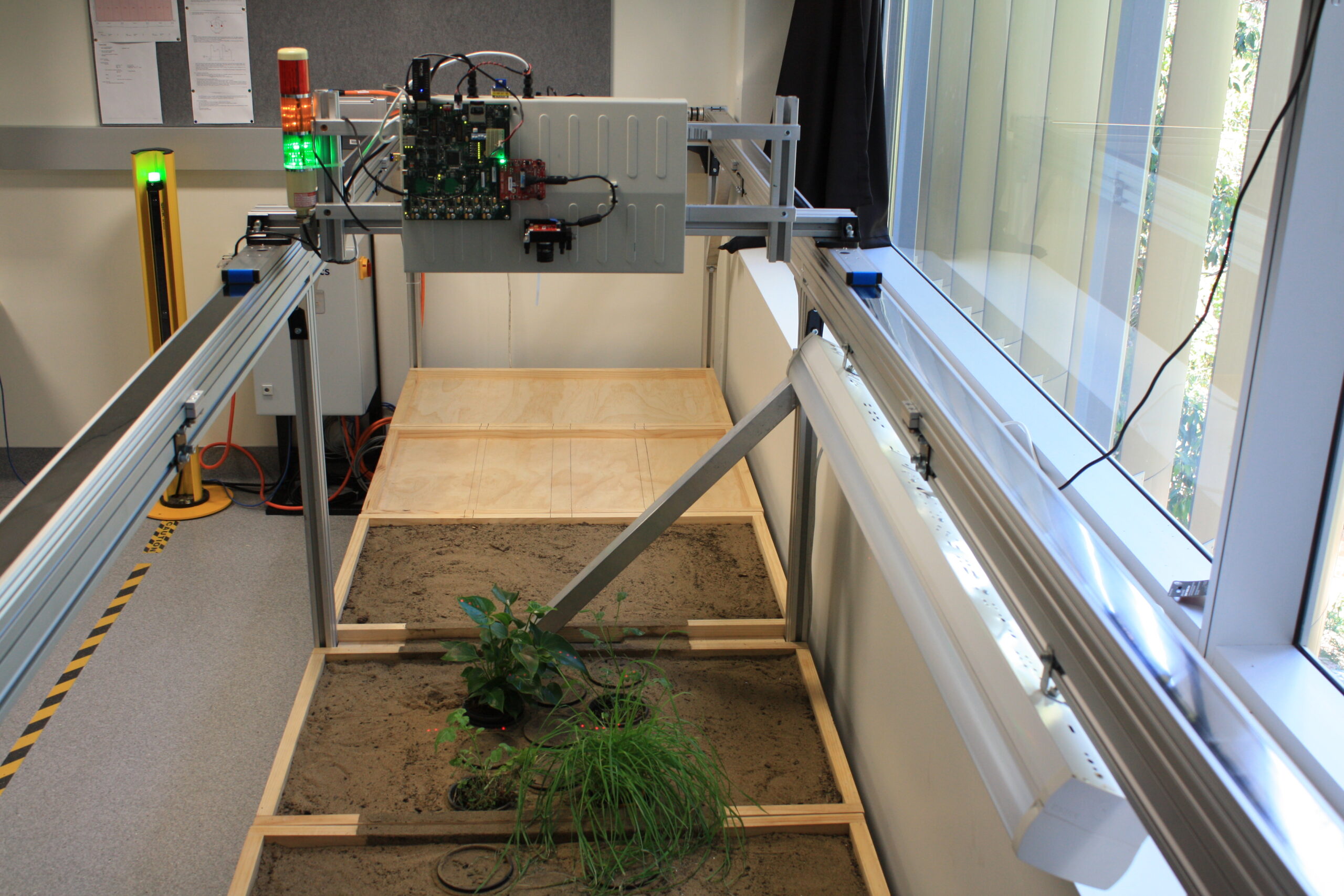

LASER BASED SENSOR TECHNOLOGY

The sensor uses cutting-edge technology to distinguish weeds from crops in real-time.

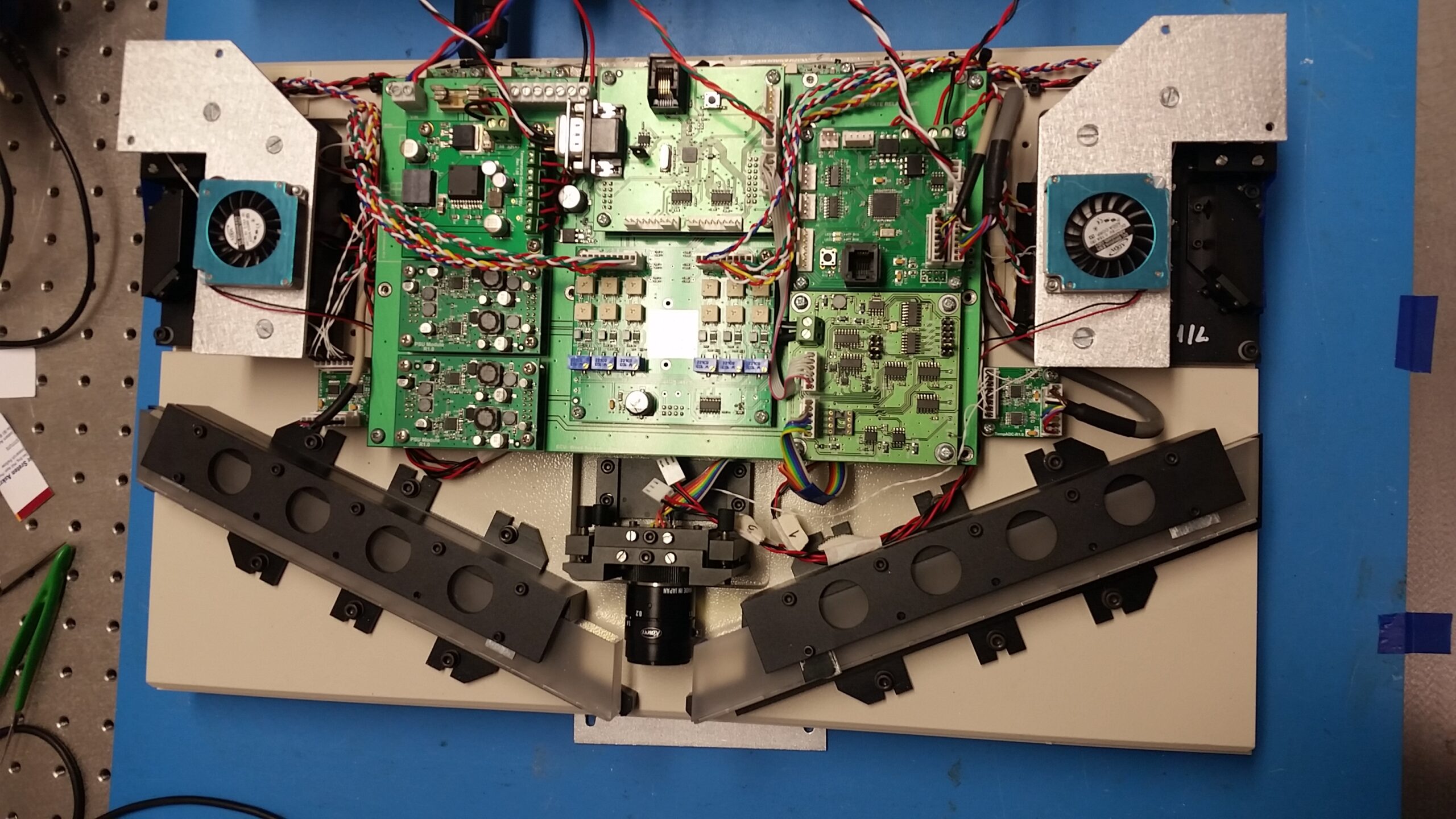

It works by shining three laser beams of different wavelengths—one infrared and two visible—onto plants.

“The triple laser beam is a world first,” Kamal says.

The lasers scan the vegetation, and information from the reflected light matches a specific weed or crop within milliseconds.

“We demonstrated the ability of the laser-based sensor to discriminate canola crops from wild radish weeds in the field with an accuracy exceeding 90% at 10km/hr.”

The ground-breaking concept attracted international interest.

FINE TUNING

The team has spent the past three years fine-tuning the system’s speed and accuracy.

An addition to the system is a camera to take pictures of the numerous crop and weed combinations found in fields.

“We feed those thousands, or hundreds of thousands of images into a super computer,” Kamal says.

The supercomputer uses algorithms to process the pictures in a similar way to the human brain.

“It’s like me showing you pictures of a pure crop, a crop with 5% weed, a crop with 10% weed…then sending you out to a field to tell them apart.”

So far, identification has focused on wheat, canola and barley, and common weeds like wild radish.

“By integrating the image recognition based sensor with the laser-based sensor, we can now discriminate canola from wild radish with an accuracy of more than 95%.”

BROAD-RANGING POTENTIAL BENEFITS

The high-tech system could save the Australian agriculture industry hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

“Weeds cost Australian farmers around $4 billion every year in management and control,” Kamal says.

The big advantage of pinpointing weeds is that expensive blanket spraying of crop fields is prevented.

Only when a weed is recognised, is it sprayed with herbicide, saving farmers money and water.

It could also mean improved crop yields, soil quality, and less environmental contamination.

A demonstration of the new integrated weed sensor is about six months away and on-farm use not too long after that, Kamal hopes.

This project is supported by the Grains Research & Development Corporation and the Australian Research Council.