Recent findings presented at the NASA Lunar Science for Landed Missions Workshop suggest we could become mole people.

On the Moon.

Scientists believe that tunnels riddle our hunk of rock in the sky, reminders of the Moon’s volcanic past. Might these tunnels provide shelter for space-going humans? Could they perhaps hide a fuel source for interstellar travel further afield? Scientists from the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute and the Mars Institute think so.

START WITH A BANG

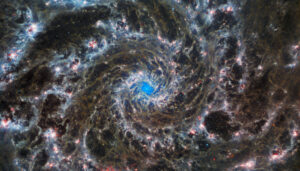

A generally accepted theory is that our Moon formed when something large (think Mars sized) collided with Earth in its early days as a lava pudding cake.

The collision smashed some of Earth’s red hot goopy bits out like a potato gun shooting into a watermelon.

These superheated bits began to scatter out around our planet but got caught in orbit by Earth’s gravity. Hanging in space, they slowly coalesced all back together into one big sphere, which we now see chilling in our skies every night.

In its early years, our Moon was the definition of an angsty teen—fiery and prone to lashing out. Which is just a descriptive way of saying it had volcanoes.

As the Moon aged, it cooled. Lava was compressed into smaller and smaller spaces even as it continued to flow beneath the crust. And as the lava drained, it left behind tunnels.

ICY POLES

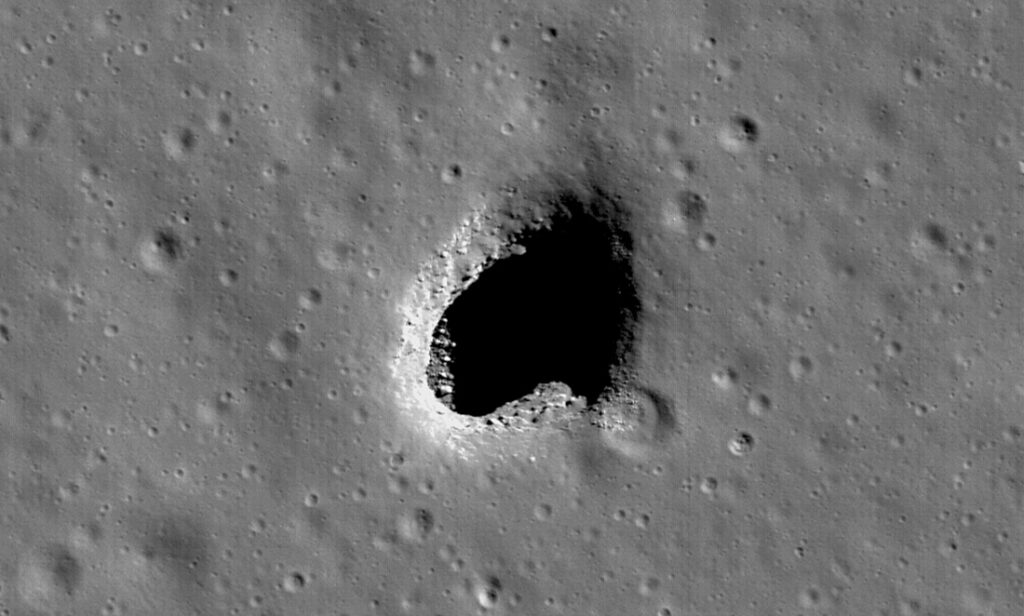

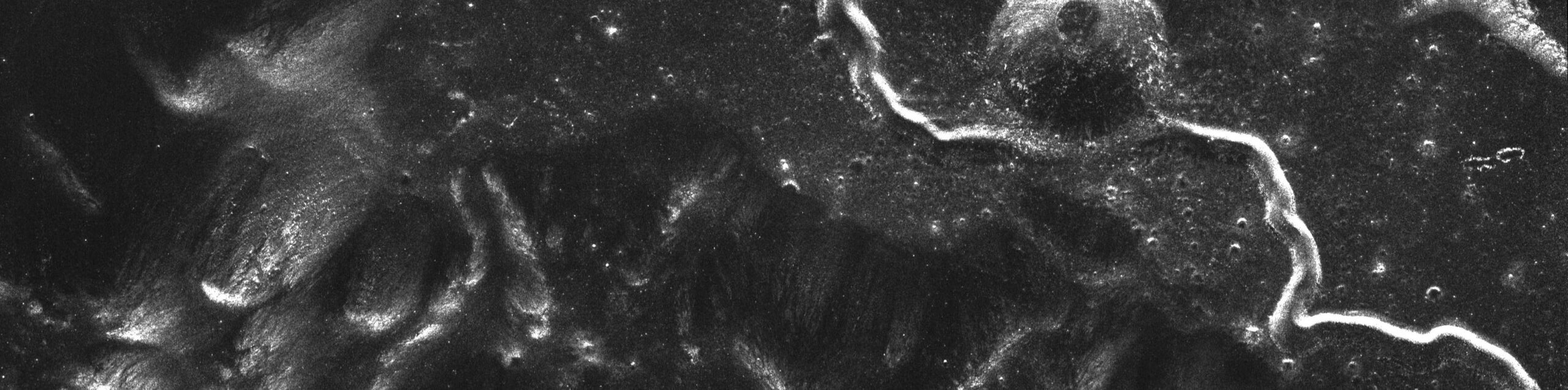

Over a couple of million years, some of these tunnels near the Moon’s surface have caved in. Thanks to these ‘skylights’, we’ve actually known about lunar lava tunnels for a little while now.

Around 200 skylights have previously been identified. These holes in the Moon’s surface are different from craters, which are caused by collisions of asteroids and meteors. Craters can be distinguished from skylights as craters have a raised rim.

So why are scientists getting worked up about more holes in the Moon?

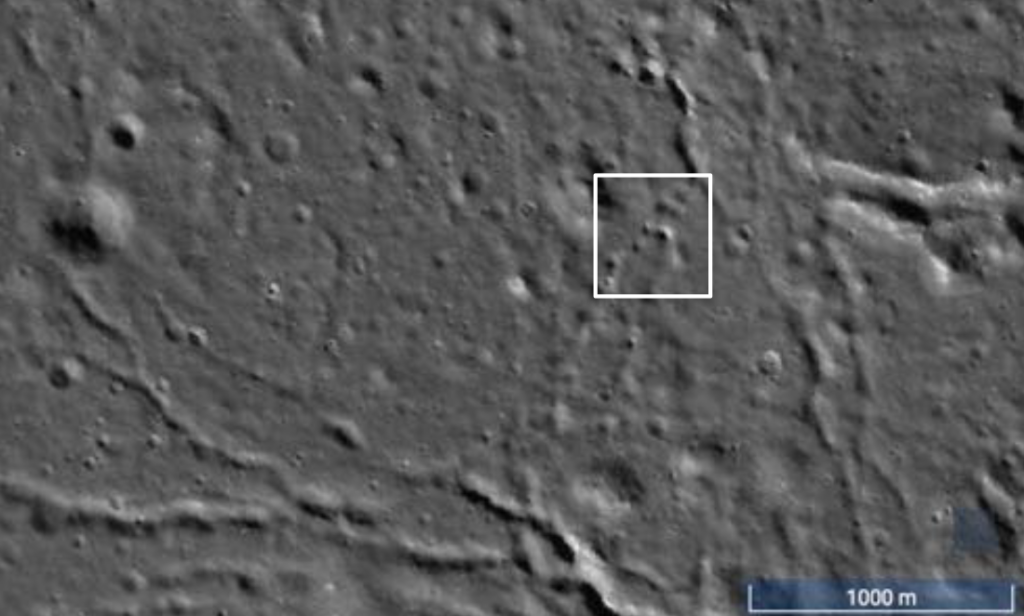

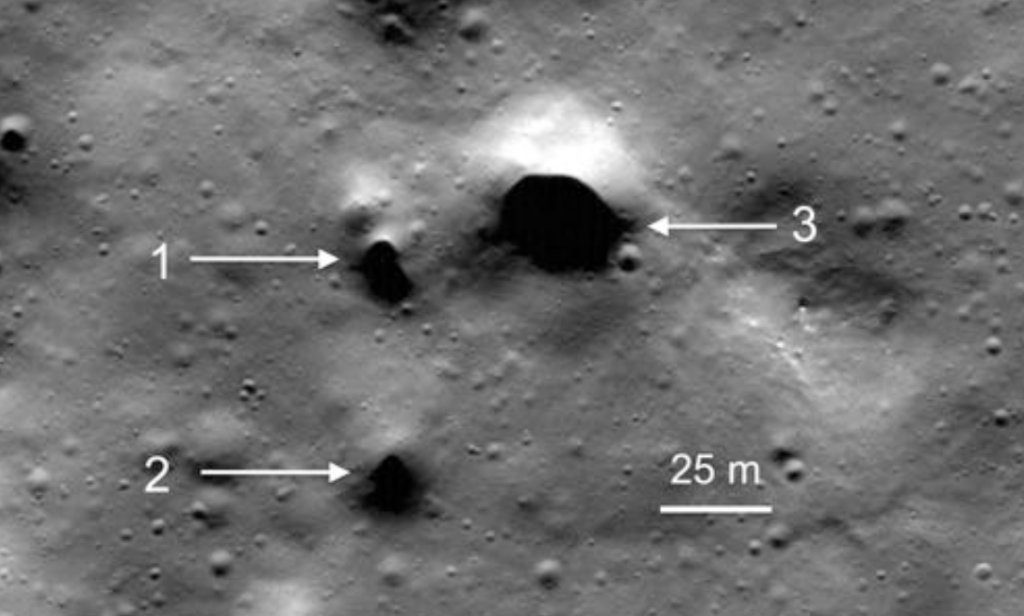

Like a 10-pin bowling ball, the latest photos (taken by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) observed three skylights clustered at the top of the Moon—although they are slightly bigger than the holes on a bowling ball, with scientists estimating their diameter to be 15 to 30 metres across.

Not unlike Earth, the Moon’s north pole is pretty chilly. It exists in constant shadow, and temperatures can reach as low as -250°C. This is where the latest skylights have been observed. The first 200 were located in sunnier climes along the Moon’s equator.

The Moon’s poles have been described as ‘cold traps’—spots where any water could have collected over the millennia. Whilst we know water exists locked in gravelly form on the surface of the poles, scientists hope that tunnels beneath the surface of the Moon could provide easy access to harvestable ice.

Obviously, this ice could hydrate a hard-working astronaut, but it could also be used to propel them further into space. By splitting up water molecules, Moon-miners could isolate hydrogen gas and use it to power a rocketship home or even onwards to Mars.

Being able to shelter below the surface of the Moon also means that celestial colonisers could protect themselves from harmful cosmic radiation.

TUNNELS ON EARTH

Donald Trump has announced a desire to see humans set their feet back on the Moon in the next 5 years. And when they get there, the astronauts will be ready to go deep.

Planet Earth has its own set of underground lava tunnels, and space agencies are using them to familiarise astronauts with subsurface science and exploration.

If you want to get a taste of what life in a tunnel might be like, you can visit some of Earth’s longest lava tunnels in Far North Queensland.

But lava tunnels on Earth and on the Moon won’t be the same. According to Riccardo Pozzobon at the University of Padova in Italy, the effect of gravity will likely have a big impact on tunnel size.

On Earth, lava tubes can be nearly 30 metres across. But Riccardo says the lower gravity environment of the Moon might allow lunar lava tunnels to be a kilometre or more across and many hundreds of kilometres in length.

Some have suggested this might allow for entire settlements to exist under the surface of the Moon.

Of course, a lot of work is required before we get to that point.

LIGHT AT THE END OF A JOURNEY TO MARS

First, what’s needed are higher-resolution images to confirm that these latest discoveries are intact skylights at the end of a tunnel.

Then it will be necessary to actually determine if the tunnels contain accessible ice. Dr Pascal Lee, the SETI researcher who discovered these new skylights, suggests that a new generation of caving astronauts or ‘robotic spelunkers’ could help greatly in this exploration.

If we can master Moon tunnels, moving to Mars may be that much easier. The Red Planet also appears to have underground tunnels from volcanic activity, leading scientists to speculate that these could house the future of the human race. So that’s our housing sorted. Now, all we have to do is figure out how to get there.