A group of astronomers from the UK, US and Japan have discovered phosphine gas in Venus’s atmosphere. Sure – so, what’s the big deal?

Catching the smell

Phosphine has the chemical formula PH3. It’s not a pleasant gas. It smells like a mix between rotten fish and garlic.

On Earth, phosphine gas comes from bacteria in marshes, swamps and other places without consumable oxygen.

But because living things are the main source of phosphine, it might mean there’s bacteria living on Venus.

“We know that these reactions happen by life on Earth, so that’s the only type of reaction that seems plausible at the moment,” says Dr Jasmina Lazendic-Galloway, astrophysics lecturer at Monash University. “Though it could be some unknown geological process.”

Non-living sources can only produce one ten-thousandth the amount of phosphine, while bacteria can produce ten times as much as observed on Venus.

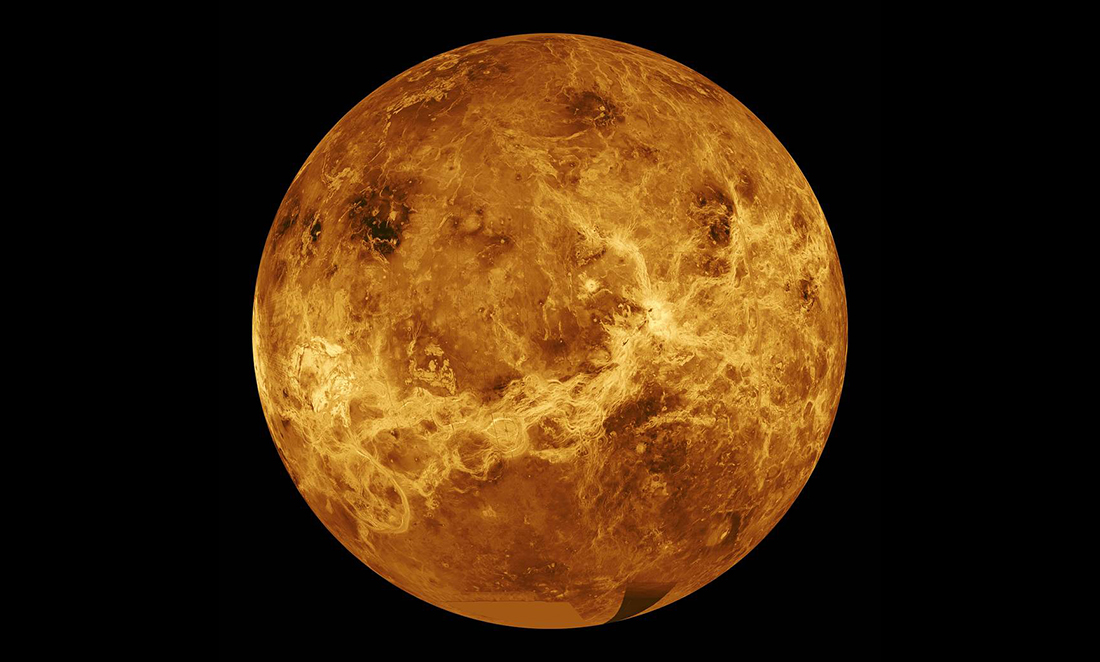

Feeling hot, hot, hot

Venus isn’t thought of as a great place for life. It’s the hottest planet in the solar system, with a surface temperature of 470°C and 92 times more pressure than Earth. It’s hot enough to melt spacecraft electronics and heavy enough to crush a submarine.

It also has a thick atmosphere of carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid. These acidic clouds have massive lightning storms.

In short, not a good holiday spot.

But astrophysicists like Carl Sagan have said bacteria could live in Venus’s cooler upper atmosphere. There are species of bacteria on Earth who are quite happy to live in volcanic vents and acid pools.

“Life adapts quite extraordinarily. There was always this idea that there could be bacterial life in Venus’s atmosphere,” says Jasmina.

SCOPING OUT LIFE

The astronomers used spectroscopy from two telescope arrays to find phosphine: the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimeter Array.

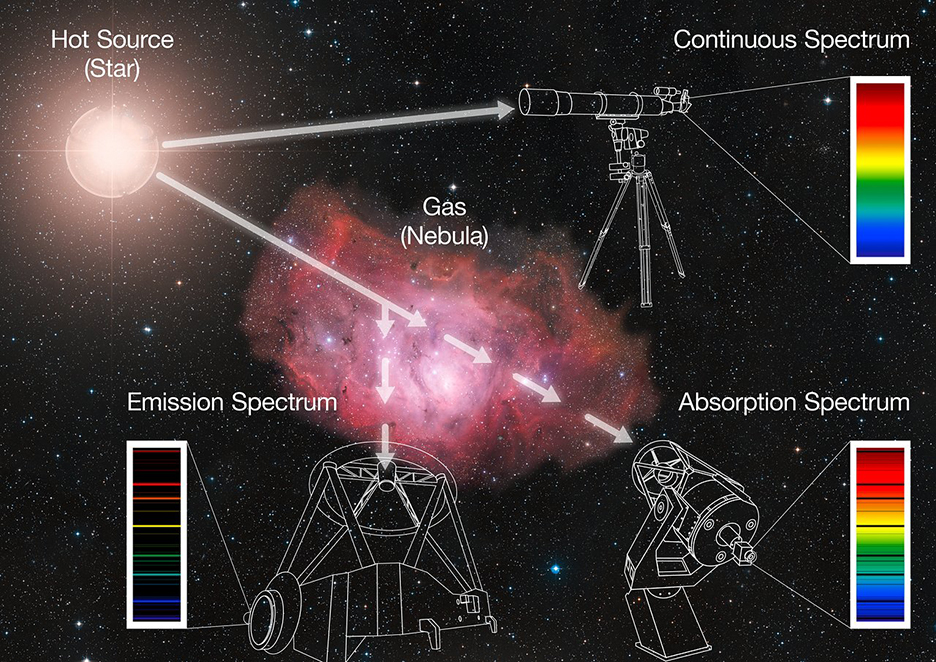

Spectroscopy helps chemists identify chemicals. Molecules reflect or absorb different wavelengths of light based on their shape and the elements they hold.

You can think of wavelengths of light as colours. Wavelengths go from radio-waves, to red colours, to blue, to ultraviolet and beyond. Each colour is a specific wavelength.

You can figure out the wavelengths a molecule absorbs in a lab. Once you know this, you can point a telescope at a region of a planet. This will show you which wavelengths are being absorbed and what molecules are in the atmosphere.

That’s exactly what the scientists did.

“There was some scepticism that it may have been a telescope error. They checked through all their data, then used a second telescope. It still showed a very strong spectral peak midway between the pole and the equator of Venus,” Jasmina says.

That makes the telescope results some pretty compelling evidence. But to find out why the gas is there – and if living things are making it – we’ll need to send a mission.

With two NASA Discovery missions due to go to Venus in the next few years – VERITAS and DAVINCI+ – hopefully we’ll know soon.