On June 23, the long-awaited release of the first images from the Vera Rubin Observatory took place. That’s quite a sentence, so let’s unpack it in detail.

The Vera Rubin Observatory is a newly constructed telescope facility in the mountains of Chile, where it sits high above the thickest part of the atmosphere, giving it a clearer view of the night sky.

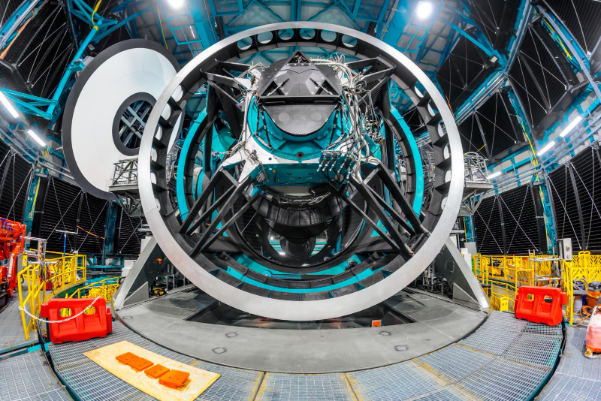

Credit: Rubin Observatory/NSF/AURA/B. Quint

The telescope is fully automated and has a very specific mission: Map the entire sky every three nights for the next 10 years. Rather than spending hours doing long exposures of extremely faint objects, Rubin will do short exposure snapshots and slowly build up layer after layer of data, allowing even the faintest of objects to shine through.

More importantly, the 3-day turnover means that Rubin returns to the same patch of sky every few nights. This means it will spot things that happen fast. Whether it is an undiscovered asteroid zipping across the sky, or an exploding star suddenly appearing in a far-off galaxy, the ability to rapidly view the whole sky in detail every few days puts Rubin into a very special class of telescope.

SIZE MATTERS

Rubin is enormous, both in size and scope (hah!). The heart of the observatory is the 8.4m diameter Simonyi Survey Telescope. The special design of the telescope mirror allows it to see a patch of sky about 50 times larger than the Full Moon, focusing the light onto a digital camera with a staggering 3.2 gigapixels. Each picture it snaps collects about 300 times as much information than a typical smartphone camera. Estimated to take about 200,000 pictures per year, Rubin is expected to generate around 60,000 terabytes of data over the lifetime of the survey.

Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA/P. Horálek (Institute of Physics in Opava)

After exposing the camera to the night sky for the first time in October 2024 – ‘first light’ as it is called, the first public release of imagery really is only a snapshot (hah!) of what is to come. You should really click this link to see Rubin’s imagery for yourself.

What’s in a name?

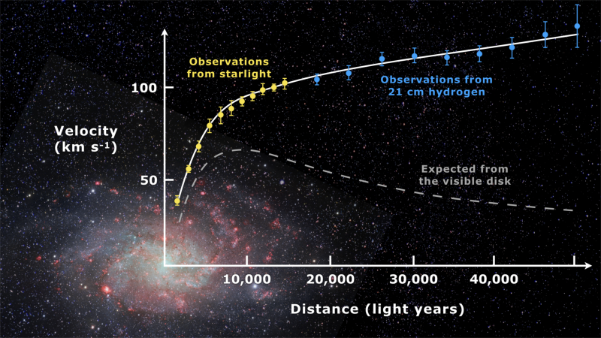

The observatory is named for the American astronomer Vera Rubin, best known for her groundbreaking work in studying galaxy rotation rates. At the time, it was expected that stars on the outer edge of galaxies would move slower than stars closer towards the middle, much like how the planets in our solar system behave – Neptune moves a lot slower than Mercury!

Rubin’s research uncovered the exact opposite. The ‘galaxy rotation curve’ as it is called, did not drop off, rather it seemed to flatten out, indicating that stars on the outer edge were moving at the same speed as those nearer the middle.

Credit: By Mario De Leo – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

The problem this creates is the same as the feeling you get when driving around a roundabout too quickly. The tendency to get ‘flung outwards’ would cause a galaxy rotating at this speed to fling itself to pieces and be torn apart.

The fact that galaxies don’t fling themselves to pieces leads astronomers to conclude the gravitational force holding the galaxy together is much stronger than expected. To account for this extra gravity, astronomers were forced to introduce dark matter, an unseen component of galaxies that provides the extra mass to hold the galaxy together.

No dark matter = no galaxies. Finding the first solid evidence for the stuff that literally holds galaxies together is a pretty good reason to have an observatory named after you.