The Casual Observer

January continues the season of Birak, and the hot weather isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

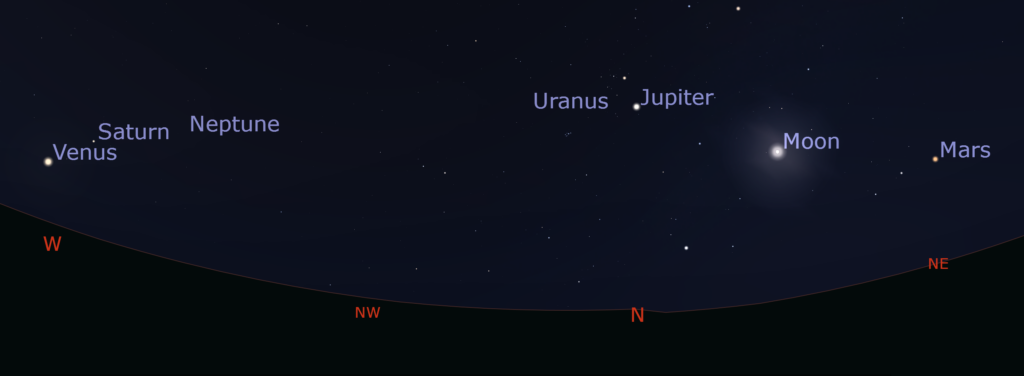

The night sky presents a parade of planets to admire. If you go outside at 9pm any day of the month you will see Venus, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars and – with a telescope – Uranus and Neptune. If you’re looking between Jan 2 – Jan 15 you’ll also see the Moon as well. Set a reminder to catch this spectacular display.

Why are all the planets lined up so neatly? Because the solar system is level – all the planets orbit the Sun in the same plane called the ecliptic – so you can trace your finger from Venus to Mars through the other planets across the sky and visualise the ecliptic.

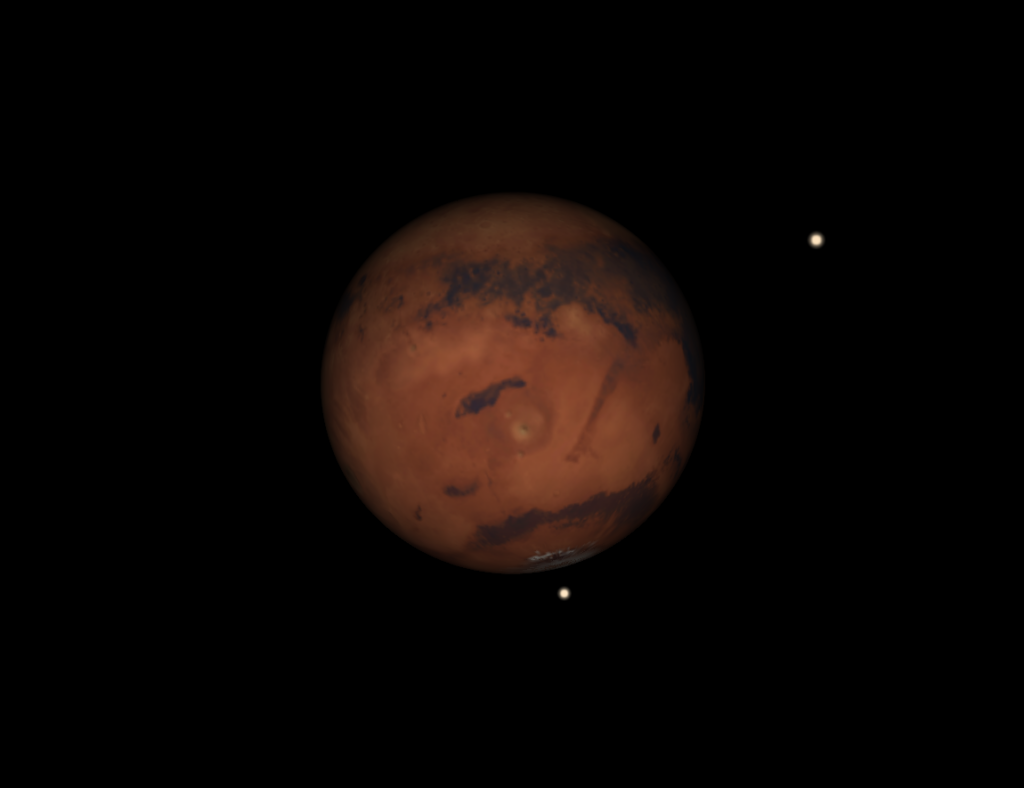

Mars reaches opposition on Jan 16, meaning it is opposite the Sun in the sky. Point one hand at Mars and the other at the Sun and you will be pointing in opposite directions. This means that the red planet rises as the Sun sets, and it is visible all night. This is the best time over the next 12 months to view Mars, so make sure you take the chance.

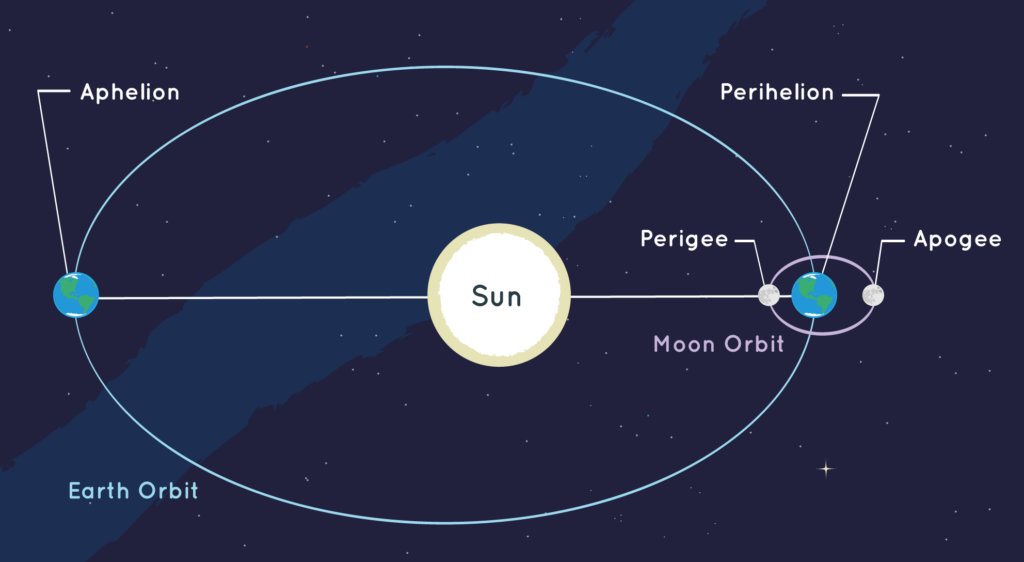

Earth reaches perihelion on Jan 4, the point on its orbit where we are closest to the Sun. Earth’s elliptical orbit takes us from a minimum distance of 147 million km in January to a maximum distace (apheloin) of 152 million km in June and back again over the course of a year, and on Jan 4 we reach the closest approach.

It is worth pointing out once again that Earth’s proximity to the Sun is not what causes the seasons (it’s winter up north right now, remember!). While Earth’s variable distance to the Sun does have an effect on temperature, on the scale of Earth’s orbit the result is only a couple of degrees. The tilt of the Earth, currently pointing the southern hemisphere towards the Sun (and the northern hemisphere away) has a much greater effect and is the reason for the seasons. It’s all because of the tilt.

Moon phases

Jan 7: First Quarter

Jan 14: Full Moon

Jan 22: Third Quarter

Jan 29: New Moon

Dates of interest

Jan 3: Moon near Venus

Jan 4: Moon near Saturn

Jan 4: Earth at perihelion

Jan 16: Mars at opposition

Jan 23: Mars near Pollux

Planets to look for

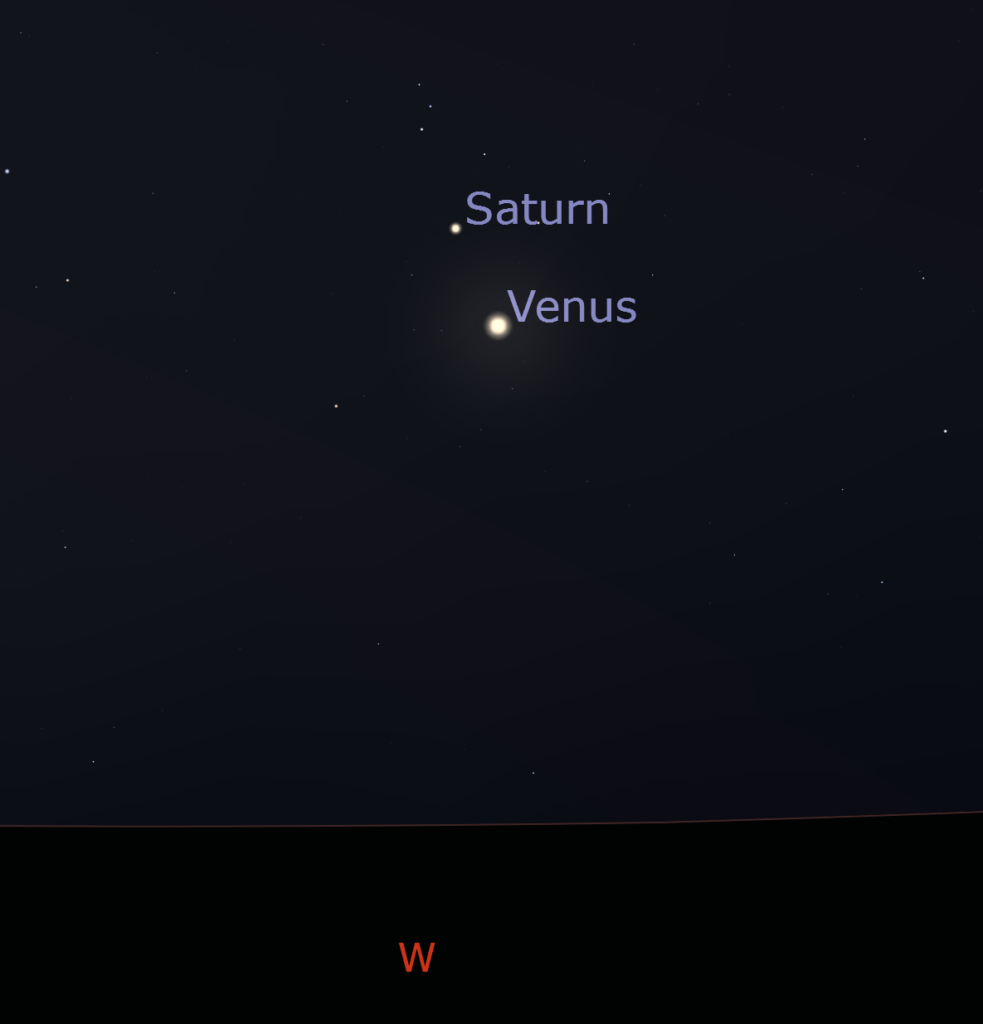

Venus and Saturn are in the west all month after sunset, getting lower to the horizon as the month progresses. They have a close approach on Jan 18, separated by just over 2 degrees, and are within a handspan of each other for a week either side of this date. They are both moving closer to the line of sight to the Sun, meaning January is really your best chance to get a last good look at them, especially Saturn.

Mercury is visible above the eastern horizon in the hour or so before sunrise for the first half of the month before once again being lost in the glare of the rising Sun.

Mars is at opposition this month and makes for excellent viewing all night, while Jupiter continues to slowly move through Taurus in the north, contrasting nicely with nearby Aldebaran.

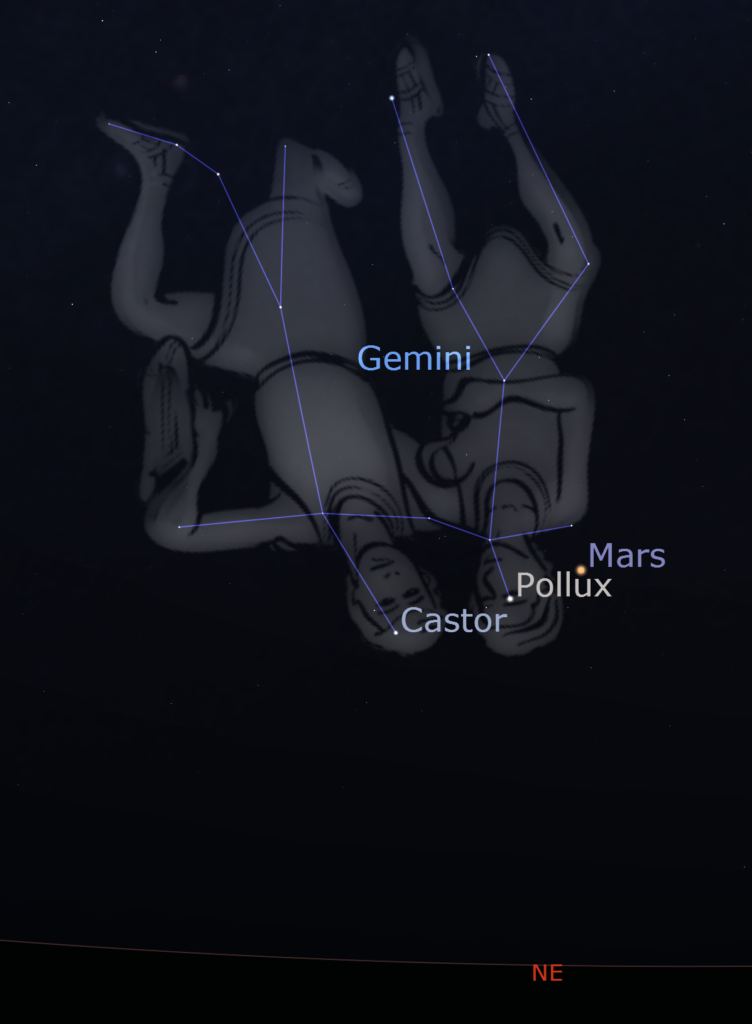

Constellation of the month

Gemini – The Twins

Gemini is a medium sized constellation visible low in the northern skies during the early months of the year. It is most easily spotted by looking for its two brightest stars – the red giant Pollux located 34 light years away, the closest red giant to the Sun in fact, which may have a planet orbiting it – and the 6-star system Castor, consisting of 3 pairs of stars orbiting each other in a complicated arrangement.

The constellation is often associated with the twins of Greek mythology, the namesakes of these two brightest stars who appear in many stories including The Iliad – as soldiers beseiging legendary city of Troy – and in the story of Jason and the Argonauts on the quest for the golden fleece.

According to some myths, Castor was born mortal, son of Tyndareus, but Pollux was the son of Zeus and therefore immortal. When Castor was slain in battle, Pollux was inconsolable and asked to renounce his immortality. Zeus agreed, and now the two brothers are united in the night sky as the two brightest stars in the Gemini constellation.

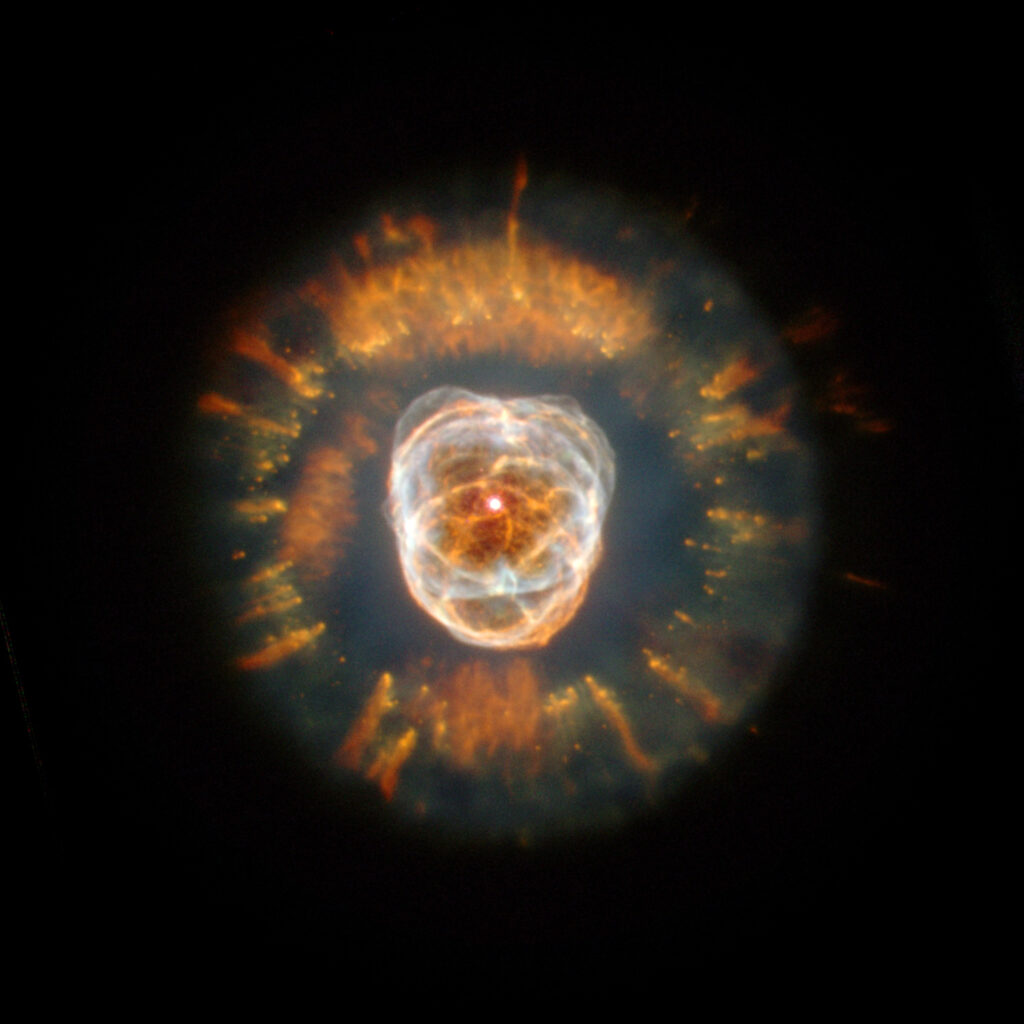

Gemini is home to the Eskimo Nebula, a planetary nebula that apparently visually resembles the head of a person wearing hooded clothing.

Despite their name, planetary nebulae have nothing to do with planets. Instead, they are the last gasps of dying stars. As Sun-like stars run out of fuel in their core, they expel the outer layers of their swollen atmospheres into space – a bubble of this ejected material forms the ‘face’ of the Eskimo Nebula in this case, with the remaining dying star visible in the very centre. The ejected material exposes the white-hot core of the star, so hot its intense radiation ionises the ejected material causing it to glow as a nebula. Since stars are round and tend to eject matter in all directions, planetary nebulae are usually roundish in shape, leading early astronomers to confuse them as ‘fuzzy planets’, and hence where the misleading name comes from.

Objects for the small telescope

Mars

This is the best time to see the red planet for the next couple of years. At opposition not only are Earth and Mars as close together as they will be, but we are also seeing Mars face on, so its fully illuminated side is presented in our direction. Although opposition occurs on Jan 16, you may find it easier to wait a couple more days before observing while the pesky Waning Moon moves a bit further to the east away from Mars. Mars will continue to be visible in the evening sky for about the next 7 months, but it will only get less impressive after this month so make sure you seize the opportunity.

Messier 35 and NCG 2158

On the far western edge of Gemini you can see two open clusters in the same line of sight. Messier 35 is a loosely bound open cluster containing more than 500 bright stars covering a region about the size of the Full Moon in the sky. In the same field of view is the older and more distant NGC 2158. Being older, all this cluster’s blue stars have expired, leaving the lighter and longer lived yellowish stars behind and giving the cluster a noticeably yellower colour than M35. Despite their line of sight, the two clusters are not related.