It’s so far away that getting out there involves flying, not driving – and when you do visit, you live, eat, and work in the same place, because the idea of flying you home at the end of every shift is absurd.

In the past, the work you do might have needed whole teams of people. Now, increasingly, it’s automated, with the most dangerous or boring work performed by robots controlled from thousands of kilometres away – or even making decisions on their own.

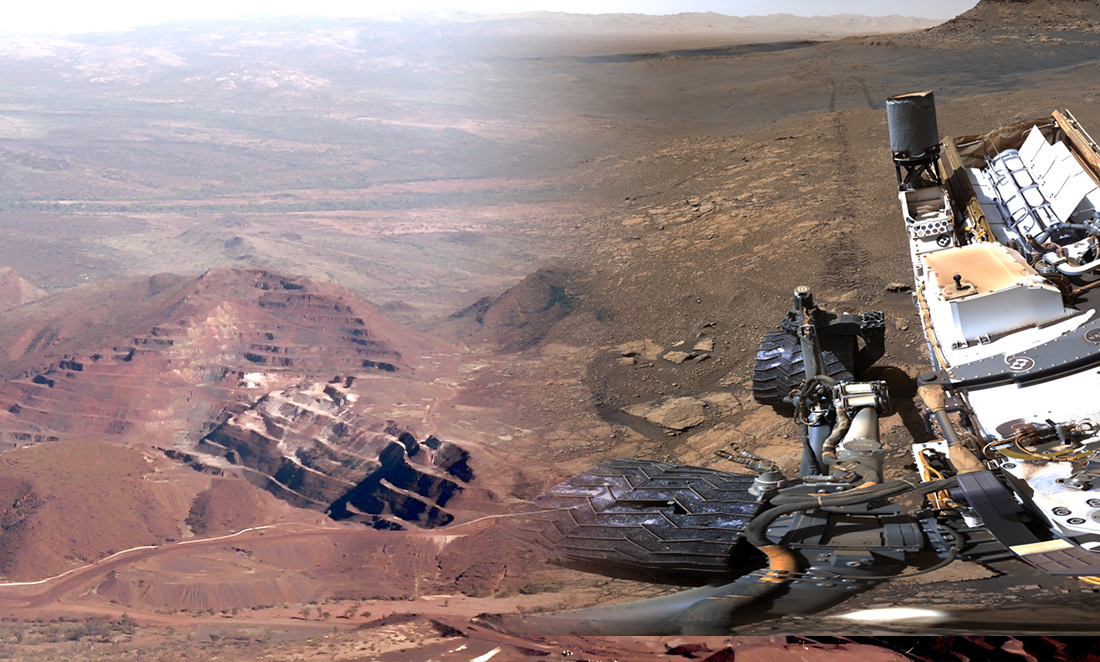

Are you an astronaut in outer space, or an engineer working in remote WA?

Common ground

It turns out the expertise you need to work on something in a harsh, far-away environment is pretty universal – no pun intended. AROSE (Australian Remote Operations for Space and Earth) is a new group hoping to take advantage of that.

“Australia has a lot to give to the international spacefaring community when it comes to remote operations,” AROSE chair Russell Potapinski said at a recent event held at the US consulate in Perth.

“The tyranny of distance we have here in Australia has led to advances in the technologies.”

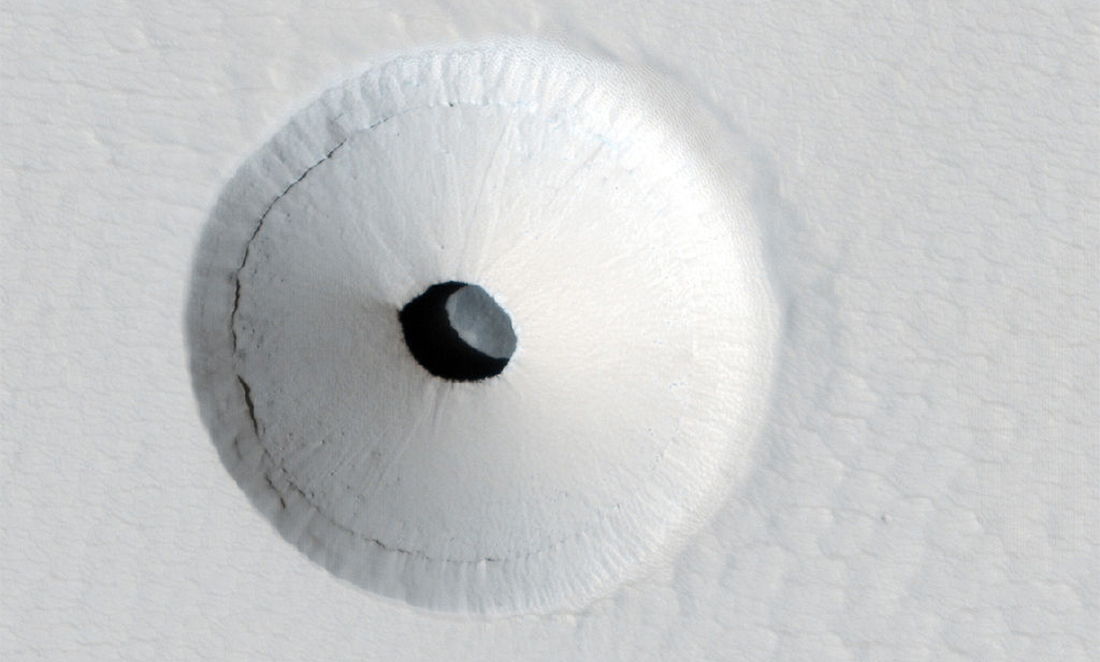

Much like the contents of the Earth’s crust, astronaut time is valuable. It costs at least $55 million US to send an astronaut to space – so having them do boring stuff is a massive waste of time and money. And, as NASA found out in the 1970s, if you try to force astronauts to perform menial tasks on a very rigid schedule, they don’t always cooperate. The crew of Skylab famously went on strike until their schedule was made a little more humane.

“Having automated systems that can move the equipment, the experiments, the food, the water, the fuel, so that the astronauts can spend time advancing humanity’s knowledge, not filling racks of equipment,” says Russell.

And it might help prevent another astronaut rebellion too.

Lending NASA a helping hand

One hurdle is that the current spacecraft are designed with humans in mind, not robots. The tools used to put it together, the knobs and handles used to operate things, and the handholds and footholds used to get around, are all designed for people.

So, if you want a robot that can work unassisted on the space station, you kind of need one that moves and handles objects like a human.

“That’s the cutting edge of robotics right there – and a three-year-old can do it.”

“Just because something is simple doesn’t mean it’s easy.”

Russell previously worked with NASA to deploy their Robonaut, a robot astronaut from the ISS, here on Earth.

“It’s that exact same technology, opening valves or pushing buttons, and manipulating equipment that was designed by humans for humans.”

Signal delay

So how do we help run the station – or build a Mars base – from that far away?

Here on Earth, we have the option of remote control. Once we head further out, that’s not really an option.

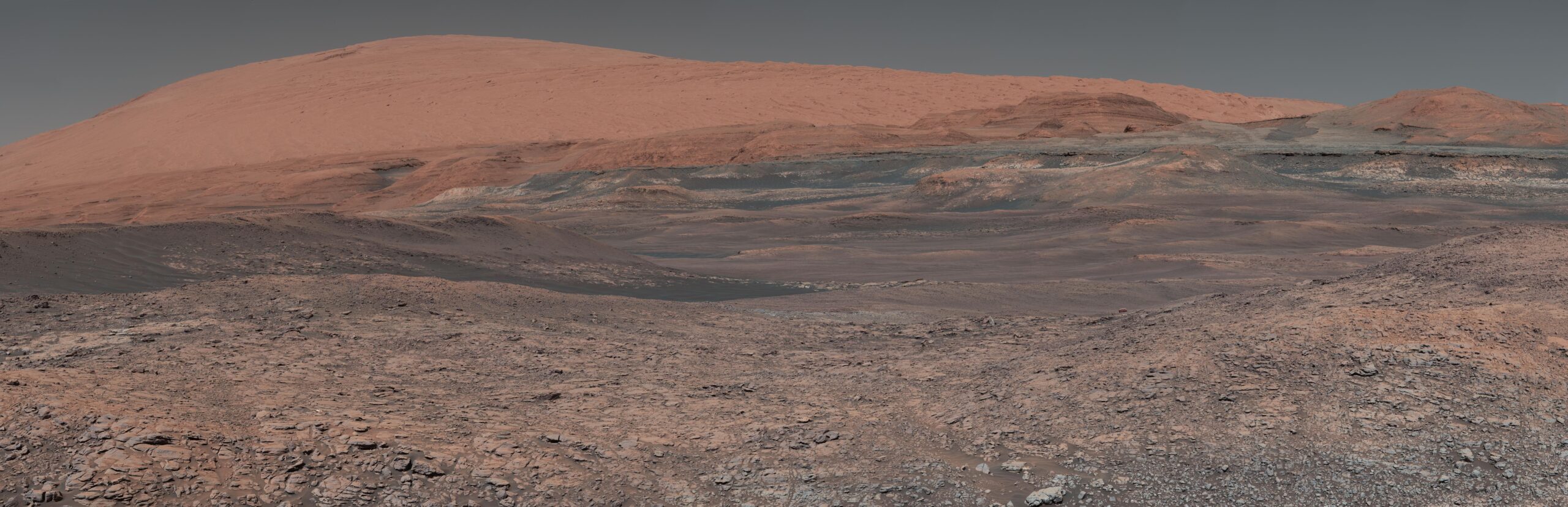

Even with the planets at their closest, and even travelling at the speed of light, it’s still at least a 5-minutes time delay for a signal to get out to Mars. If you’re driving earth-moving – or, Mars-moving – equipment, that’s way too long to be practical.

One idea is that astronauts could ‘supervise’ building their base from orbit, the same way we do with mine sites from Perth. Another, which AROSE is more excited about, is AI.

“Autonomy eats lag for breakfast,” says Russell.

“We don’t actually need to do each and every little motion and wait for the light delay to go back and forth.”

“We can just say, ‘Mars Rover, I want you to do that’, and get a confirmation that it’s been done correctly.”

NASA are already doing this on Mars. In 2017, NASA handed over control of the laser on the Curiosity rover to an automated program. Rather than wait for commands from Earth, it now chooses, zaps, and analyses rocks entirely on its own.

Hey siri, open the pod bay doors

Handing over parts of the mission to AI like this might need us to change the way we think about them – and the way we test them, Russell says.

“I think we’re going to have to treat the AIs much more like we treat people. They’re not people, but we’ll have to test them like they are.”

It’s less like writing software, he says, and “more like certifying a pilot.”

It’s a giant leap for NASA, which likes its software close to perfect, but it looks like it might be the future of space exploration – and the best chance the rest of us have to get into space.