Recently, 47 new ‘marsquakes’ (that is, quakes on Mars) have been detected by Professor Hrvoje Tkalčić from the Australian National University and Professor Weijia Sun from the Chinese Academy of Science. The discovery suggests Mars to be more seismically active than previously thought.

The findings also provide clues about the composition of Mars and how other rocky planets in our Solar System formed billions of years ago.

I feel the Mars move under my feet

First of all, if you’re wondering how to measure quakes on Mars, the answer is deceptively simple.

Send a robot up there!

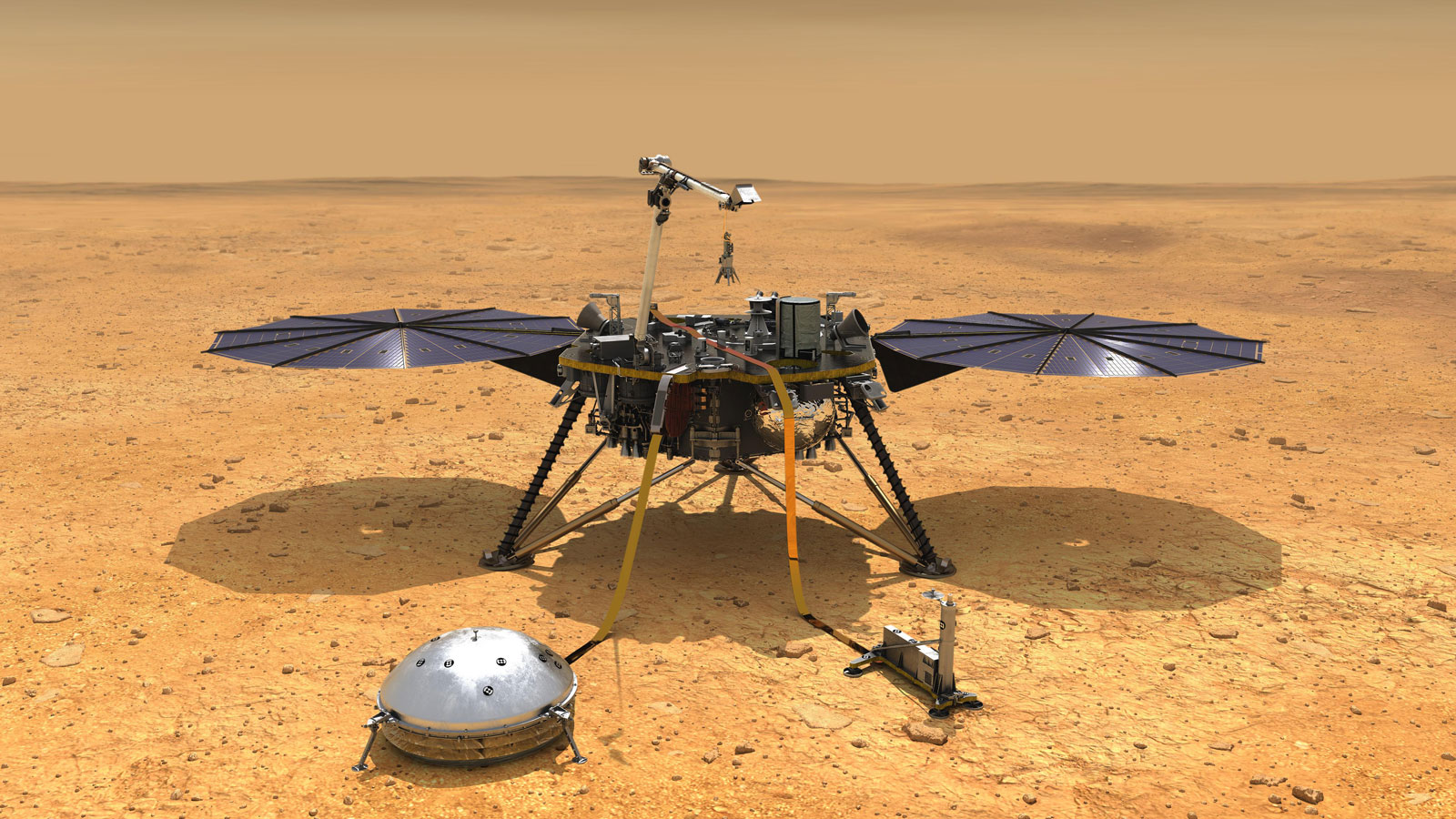

Hrvoje’s and Weijia’s research was based on seismic data collected by NASA’s InSight Mars lander.

InSight is the first outer space robotic explorer to study the Red Planet’s crust, mantle and core in depth.

InSight’s instruments, including a seismometer, have probed the Martian subsurface since November 2018.

Previously, tectonic forces were thought to be responsible for marsquakes. But this is being challenged by the new study.

The marsquakes discovered by Hrvoje and Weijia all occurred in the same area, suggesting they were caused by the movement of magma in the Martian mantle (try saying that quickly!)

“Magmatic and tectonic processes are both caused by a planet’s internal activity,” says Hrvoje. “However, Mars has a single tectonic plate while Earth has more than a dozen. So the dynamics are quite different.”

Piecing together a picture

Studying seismic data allows geophysicists to peer inside a planet.

“Like on Earth, quakes generate seismic waves that move through the planetary interior,” says Hrvoje.

“These waves are interpreted with sophisticated imaging methods, similar to how a doctor uses an X-ray to image the human body.”

Like a doctor, geophysicists can use these images to understand how things work and how the planet formed. An important area of study is Mars’ magnetic field – or lack thereof.

It’s magnetic

Earth’s magnetic field is a vast, comet-shaped ‘bubble’ that protects our planet from harmful cosmic radiation. Without it, Earth would be uninhabitable.

“Mars once had a magnetic field, but it died millions of years ago,” says Hrvoje.

“That had catastrophic consequences for the potential of life development and preservation.”

So when and why did it die? They’re big questions Hrvoje and Weijia hope their work can help answer.

“If we can show that the Martian mantle is still mobile, we will have discovered important clues for scientists who are investigating the Martian palaeomagnetic field and the period of time the Red Planet may have been habitable,” says Hrvoje.

Probing deeper than ever before

There’s a long way to go for humankind’s mission to understand Mars.

“We are still in a discovery stage, and that’s what makes this field exciting!” says Hrvoje.

Since the publication of Hrvoje and Weijia’s research, the InSight detected the biggest quake ever recorded on another planet. The estimated magnitude 5 marsquake was recorded on 4 May. (Previously, the largest recorded marsquake was an estimated magnitude 4.2 on 25 August 2021.)

“This is extremely important because larger quakes often produce less-ambiguous signals,” says Hrvoje.

“The quake will be used to probe even deeper into the Martian interior and further illuminate the mantle.”

If Mars isn’t as dead as we thought, this has implications for its future as well as its history – especially if scientists hope to one day establish life on the Red Planet.