Galaxies don’t just hang around, motionless in space. They rotate around their dense cores and attract nearby galaxies using gravitational force. Sometimes these galaxies get so close they collide.

Galactic cannibalism is a version of this collision where the bigger galaxy absorbs the smaller one.

When cannibals collide

Around 25% of the galaxies within the observable universe are merging with each other. In fact, the Milky Way ripped its five most distant stars from another galaxy during an ancient merger event. It was a bit like taking a bite out of someone’s shoulder as you walk past them!

As the Milky Way cannibalised the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy, it left a trail of stars 1 million light years across.

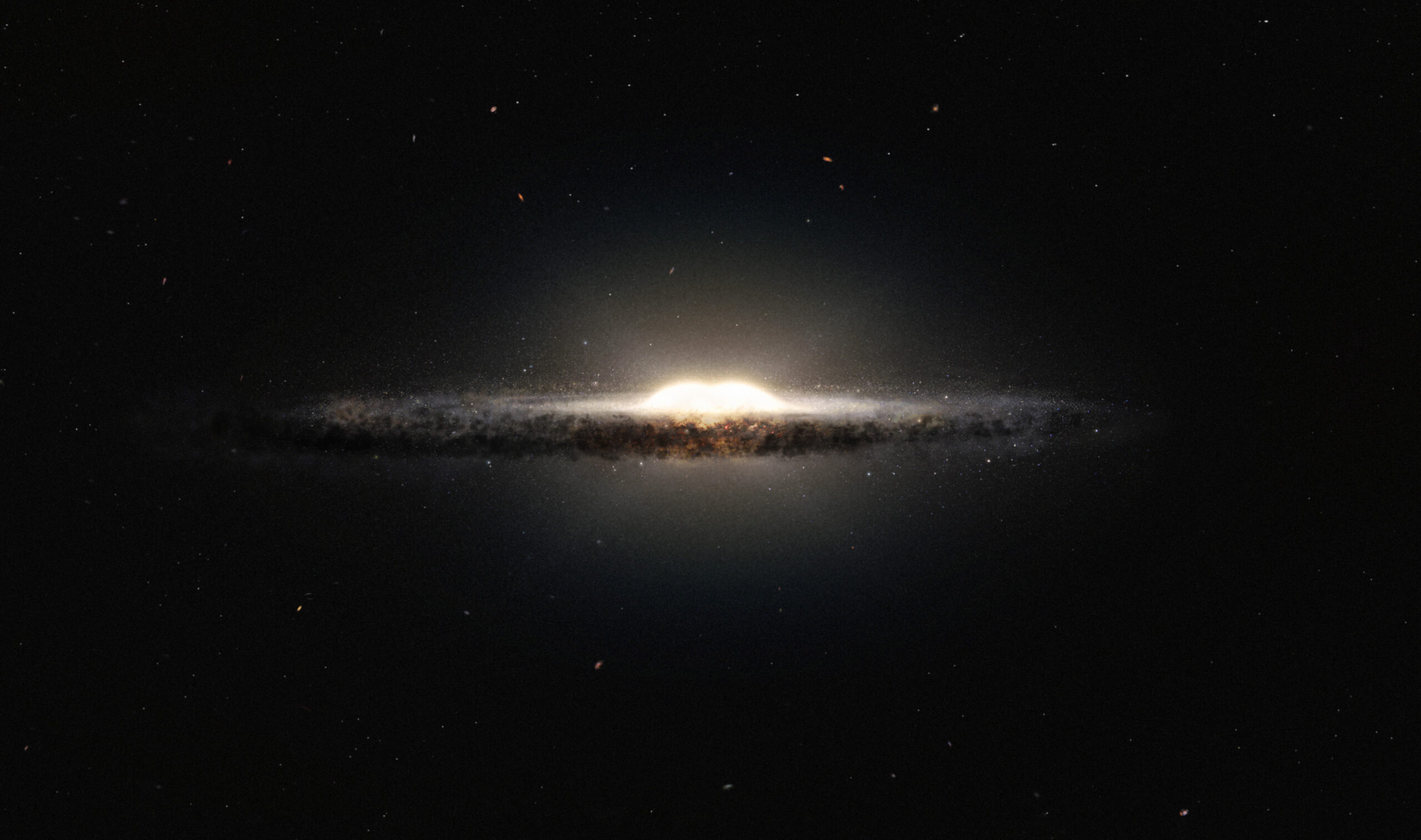

The Sagittarius Dwarf Galaxy looking a little worse for wear after the Milky Way’s snacking | NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

The average dwarf galaxy has around 1 billion stars. In contrast, our Milky Way galaxy has 100 billion stars. And on average, each of those stars has at least one planet orbiting it.

When we talk about this many stars and planets, galaxy collisions might sound apocalyptic. But the thing about space is – there’s a lot of it.

“Even in a galactic merger, we don’t expect stars to collide with other stars,” says Dr Claudio Lagos, a Senior Research Fellow at ICRAR.

“So the planetary system around one star would be untouched.”

Claudio’s research focuses on the diversity of galactic mergers.

The average distance between individual stars within the Milky Way is roughly 5 light years. To make more sense of that distance, we can reduce the scale.

If our Sun was a ping-pong ball, the nearest star would be a pea over 1000km away. That’s a lot of space to avoid a collision, but bad things could still happen.

GIPHY

“It is possible that a galactic merger ignites massive energetic activity in the central supermassive black hole of a galaxy, to the point that it could emit a lot of energy in gamma and X- rays, that could be detrimental for planets in a galaxy.” says Claudio.

Simulating the stars

It takes millions of years for galaxies to collide. So how do we know they are even happening?

One way is by analysing the chemical composition of stars. Stars made of the same stuff likely came from the same area.

Some stars have different chemical ratios or are older than their neighbours. This can be a sign that a galactic collision dragged the star across space to its new home.

Astronomers can also check the composition and velocities of galaxies. This allows them to create a model of these galaxies and work backwards. Knowing where they are, what’s in them and where they’re heading means they can ‘travel’ backwards through time to predict any collisions.

Mitchell Cavanagh is a PhD student studying galaxy evolution with neural networks at ICRAR. He says the shape of a galaxy can tell him a lot about its history.

“Galaxies that have recently undergone mergers will often be accompanied by tell-tale signatures such as disrupted galaxy discs, unusually concentrated central bulges or clearly visible debris from the collision called tidal tails.”

Two galaxies nicknamed “The Mice” showing a galactic tail | NASA, H. Ford (JHU), G. Illingworth (UCSC/LO), M.Clampin (STScI), G. Hartig (STScI), the ACS Science Team, and ESA

One of the biggest model galaxies to ever exist is the EAGLE simulation. It simulates 10,000 galaxies. And every single one of these galaxies is the size of the Milky Way or larger.

Dr Vanessa Moss is a CSIRO astronomer. She works with the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder telescope to find and catalogue galaxies.

“Data without context cannot be used to advance physical understanding of the universe. And so as scientists, we search for trends and patterns within data to make sense of the underlying physics that is driving, for example, the evolution of galaxies,” she says.

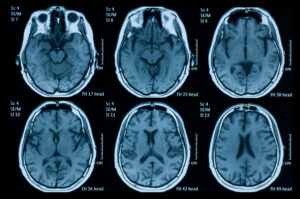

WA researchers at ICRAR trained a neural network to classify galaxies within EAGLE. A neural network is an artificial intelligence computer program built to mimic the layered structure of a human brain to solve problems.

Since EAGLE had simulated the history of each galaxy, the researchers were able to look at oddly shaped galaxies and see how galactic collisions and cannibalism changed their shape.

“Automated techniques such as neural networks excel at rapid image classification,” says Mitchell.

“This is especially useful for studying mergers in simulations, where automatic classification can save a lot of time compared to manual, visual classification.”

4 billion years, save the date

So why are galactic collisions so important?

Our galaxy is due for another collision in 4 billion years. But that’s probably not soon enough to worry about.

Maybe the best answer to that question is we should study galactic collisions because we know very little about them.

“Most massive elliptical galaxies are believed to have formed through cumulative mergers. Studying mergers provides an opportunity to understand the physical processes that drive the growth of galaxies,” says Mitchell.

As galaxies devour other galaxies, the matter they accrue allows them to forge new suns. So basically, everything we are is due to an ancient act of cannibalism.