Our Sun forms the centre of our Solar System. It’s a giant nuclear reaction full of such dense matter that it warps spacetime around it, pulling everything nearby into its orbit.

But in our Milky Way galaxy, the Sun is only one of 100 billion stars. These stars are part of a constant life cycle. They’re born from gas clouds, live their long lives and eventually die, ejecting gas throughout the galaxy to form new generations of stars. Stellar nurseries are regions of a galaxy dense with this star-forming gas.

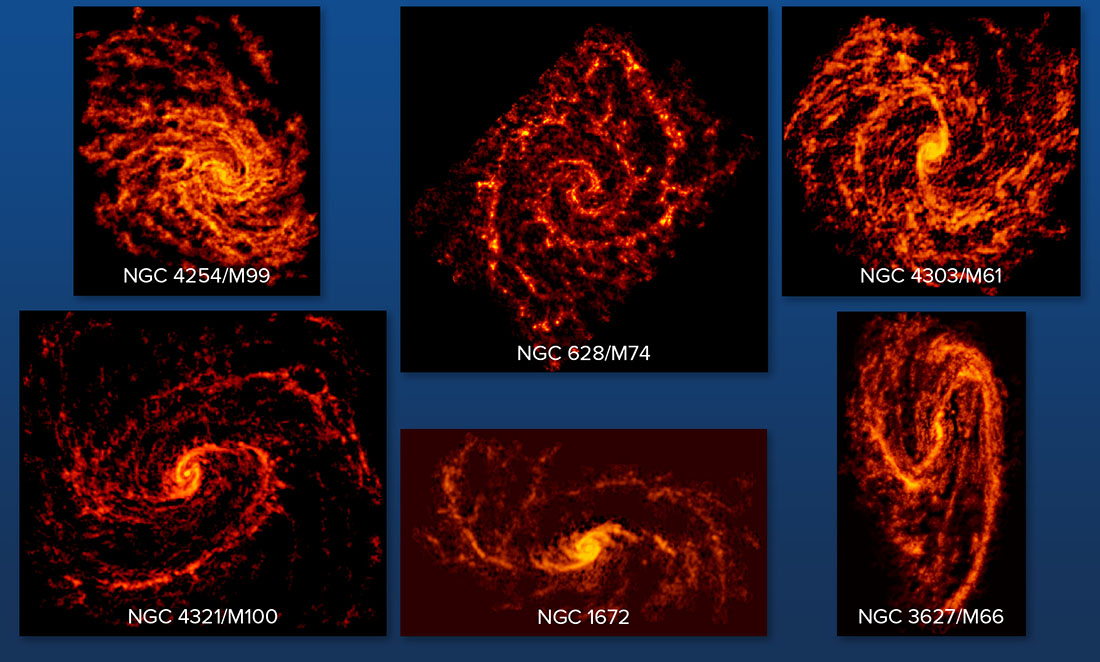

The Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby GalaxieS (PHANGS) survey uses ground and space-based telescopes to reveal how stars are born and form nearby spiral galaxies.

Dr Brent Groves is an astrophysicist at the University of Western Australia and International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR). He’s an expert on these star-forming gases and was part of the international PHANGS team that are shedding new light on the structure of stellar nurseries and formation of galaxies.

The vision they have captured has been likened to a ‘galactic fireworks display’.

A star’s spectre

“Newly formed stars blow away surrounding gas. This lights up the hydrogen emission lines of our telescopes, which allow us to work out which elements are present in those areas and where these gases are going,” says Brent.

This technique is called spectrometry. Spectrometry uses telescopes to drink in the light of the universe. Once collected, this light is split into its component parts, called the spectral bow. Different elements emit specific spectral lines, so by looking at what spectra are present from a light source, you can tell what elements are present in the source.

“So the spectrum we’re looking at splits up into this wonderful rainbow. That rainbow tells us the sort of elements from the stars in a given location and therefore the ages of the stars and where they might have come from.”

The light fantastic

The nearest galaxy in the survey is called NGC 5068. You can see it in the Virgo constellation when you look up at the night sky. It takes 18 million years for light to travel from there to here. To pick up such faint light signals, astronomers link the telescopes around the world and in space. These include the Atacama Large Millimeter Array, Hubble Space Telescope and Very Large Telescope and potentially the James Webb Space Telescope.

So what were the results? PHANGS reveals how generations of stars form, blowing away their stellar clouds in 2–3 million years (which actually isn’t a long time for a star). The massive dispersive force of these dying stars sends the gas right across the galaxy.

It shows us the universe is a more complex place than our models might assume. It is full of endless discovery, and we have only just scratched the surface.