The vast Ngarla country, also known as the Pilbara, has a long memory. Ancient jade, basalt and granite boiled up from the Earth’s crust more than 3.5 billion years ago. Today, this rock remains perfectly preserved – allowing geologists to dig into one of science’s most profound questions.

According to Dr Martin Van Kranendonk, a Professor of Geology at the Australian Centre for Astrobiology, the Pilbara provides a window to the distant past.

“You can see where the hot springs were,” says Martin.

“You can stand on the edge of a lake and see the ripples and the shoreline in the rock.”

To try and uncover the origins of some of Earth’s earliest organisms, Martin and his team analysed ancient hot spring deposits at the Dresser Formation in the Warrawoona Group.

A steamy start to life

In the hot springs they analysed, Martin’s team found the chemicals necessary for life to begin from non-life – a phenomenon known as ‘abiogenesis‘.

The findings are evidence against the popular theory that life sprung from deep sea hydrothermal vents. In the enduring theory, it’s thought that the heat and mineral-rich water in the hydrothermal vents attracted a huge diversity of microbial life, creating the ideal conditions where live organisms could form.

But according to Martin, the deep sea vent hypothesis has an Achille’s heel: water.

A change in theory

Water is vital for life as we know it.

Astrobiologists consider planets with water to be the most promising candidates for extraterrestrial life. But life’s crucial building blocks like DNA and proteins are formed through condensation reactions – which needs both the absence and presence of water.

“Over the past few years, the [astrobiology] community has shifted away from deep sea vents,” says Martin.

“There are still some high-profile people who have worked on this problem for a long time who support deep sea hydrothermal processes. But the more people investigate it, the less likely it seems to be the case.”

According to Martin, while deep sea vents can develop some geochemical complexity, they face overwhelming problems.

“It’s very difficult to make complex organic molecules in permanently wet environments,” says Martin.

“It’s much easier to concentrate elements with wet and dry cycles on the Earth’s surface.”

Let there be life

Which brings us back to the Pilbara. Three and a half billion years ago, the Pilbara was part of a supercontinent called Ur. It was a large volcanic island full of corrosive hot springs. The resulting cycles of water evaporation allowed chemicals to concentrate and increase in complexity.

The Pilbara Craton is a snapshot of life in those days. The ancient rock, buried almost everywhere else on Earth, protrudes in brilliant greens, pinks and greys. Stromatolite fossils provide impressions of Archaean life. The hot springs teem with new life, but they have changed little over time.

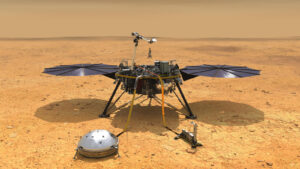

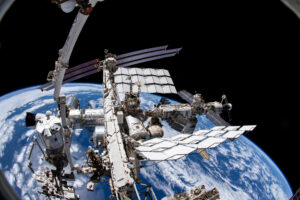

If life could evolve in these conditions, it could hint at life elsewhere in the Universe. As humankind races to colonise other planets, understanding the origins of life on Earth will help us better understand our neighbouring planets.