If you’ve ever seen a grater smiling at you, you know how quickly the human brain spots faces in everyday objects.

Seeing Jesus on a piece of toast or a man’s face on the Moon’s surface are examples of how our brains are hard-wired to facial recognition.

Now, a University of Sydney study suggests our brains process these facial expressions as if they were a real face.

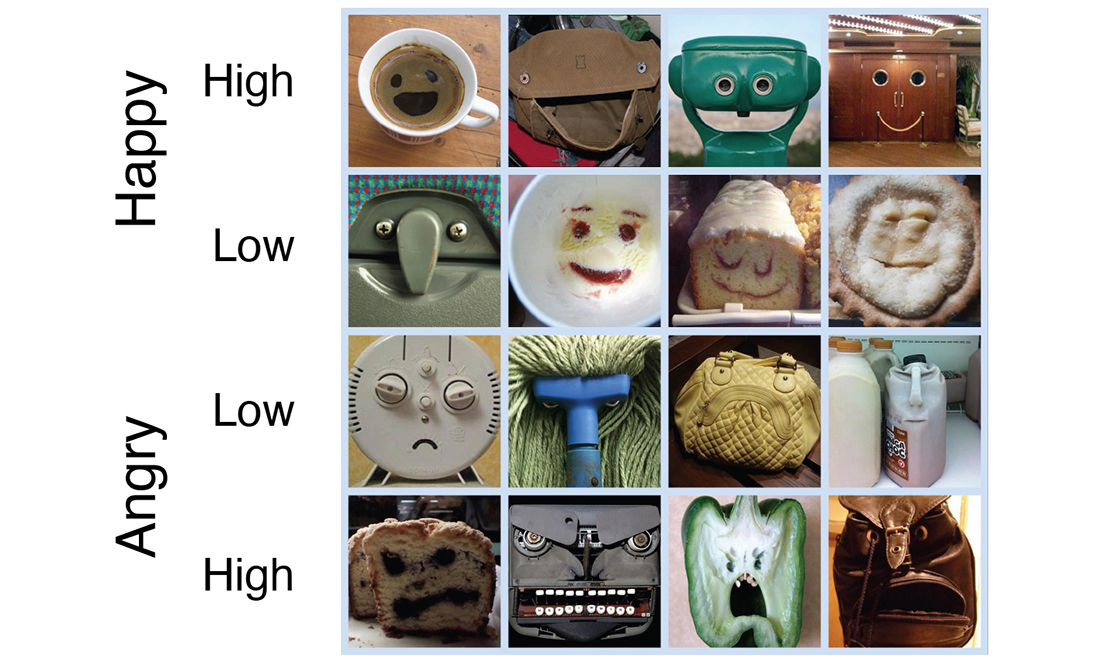

It means we can’t help but give these objects emotions – from a happy latte to a cranky mop.

Two eyes, a nose and a mouth

University of Sydney psychologist and neuroscientist Professor David Alais led the research.

He says humans are the most sophisticated social species on the planet, so it’s vital to be able to quickly recognise a face.

“We want to recognise faces because they could be family, they could be friend or foe, they could be sick or healthy, they could have all sorts of intentions,” he says.

“So you need to quickly detect the face and analyse it – that’s of evolutionary importance.”

David says we have a specialised part of our brain dedicated to detecting faces.

It works by applying a template matching procedure to everything we look at.

“Without you having to think about it, [the brain is] automatically deploying a simple template that says, ‘If I see two eyes, a nose and a mouth, then I respond’,” David says.

“It’s automatic, it’s super fast and it’s very efficient – it almost never misses a face.”

Word of the day = pareidolia

The downside of this super-speedy automatic detection system is that sometimes we get false positives.

We see faces in coffee, handbags and other inanimate objects.

It’s known as face pareidolia.

Last year, two of David’s co-authors were able to show that the same part of the brain responds to faces in everyday objects as real faces.

But the researchers wanted to take that finding a step further.

They wanted to see whether our brains immediately dismiss faces in objects as false detections or continue to process them as they would a real face.

You can’t unsee it

The study found anything identified as a face will trigger our brain to automatically extract emotion, deciding if that face is happy, sad or angry.

We’re unable to turn it off.

“It’s possible the brain realises ‘Wait, this is not a face after all, it’s an object’,” David says.

“And yet, somehow, every time you look back and see that configuration of two eyes, a nose and a mouth, it retriggers the face processing system.

“Because it’s automatic and rapid, you can’t really not see it … you can’t help but reactivate this system every time you glance back.”

Emotional emojis

David points to emojis as an example of how fake faces can carry enormous emotion.

“Something doesn’t have to be a real face to convey emotion, and in fact they’re super effective,” he says.

Another potential application is for robots in aged care or health.

“You could envisage robotic faces that have emotional expressions that are actually going to trigger a person’s brain in the same way as a real carer,” David says.

“So it might be significant after all.”