For historical archaeologist Sean Winter, looking at the things that people leave behind reveals a whole new side to the history of buildings.

“Putting together a picture of the past is like taking a 1000 piece jigsaw puzzle, throwing away 800 pieces and then putting what’s left together and trying to understand what the picture’s actually showing you,” Sean says.

Surprisingly, one can find a treasure trove of figurative jigsaw pieces beneath house floors.

“As humans, we spend about 70% of our time inside, so it makes sense that we’d leave an imprint behind,” says Sean.

“As soon as you realise how many items survive underneath buildings – items that wouldn’t in typical outdoors archaeology – suddenly you can find out a whole heap of things about how people lived.”

Underfloor exploration

After working closely with National Trust archaeologist Leanne Brass, Sean started thinking about WA’s colonial buildings as archaeological sites instead of pieces of architecture.

Sean investigates these sites using scientific techniques to better understand human behaviour (aka experimental archaeology).

In 2017 and 2018, Sean and his team excavated under-floor at the Residency Museum in York and the Ellensbrook Homestead in Margaret River. As they started analysing what had been uncovered, they had some questions.

“First, we had to refine what ‘big’ and ‘small’ actually means,” laughs Sean.

“OFTEN, IT WAS PURELY ABOUT THE PHYSICS OF WHAT CAN GET THROUGH GAPS AND SPACES.”

Knowing this, there was room to reassess whether an item found under the floorboards was simply lost or had been deliberately placed there – and if so, why?

Keeping culture on the down low

Sean and his team were a little bit floored by what they found underneath Ellensbrook Homestead at Mokidup (Margaret River).

Built in the 1850s, the homestead once operated as a ‘Farm Home for Aboriginal Children’. Between 1898 and 1917, Indigenous children were sent there to learn domestic and farming skills.

Hidden beneath the floors were delicate materials like cotton embroidery, paper and animal fur – items that don’t often survive the elements. This was partly due to the installation of lino in 1920, which helped to seal the area.

But they also found items that were deliberately hidden. Shells, shards of glass and pieces of quartz were all found under the floorboards in certain rooms of the house.

It was a secret collection saved by children who were denied toys or trinkets – or cultural identity.

“You see this in institutional mission sites all across Australia,” says Sean. “These artefacts show that people were trying to preserve links to their Aboriginal culture.”

Pairing these discoveries with detailed institutional records and photo collections, a clearer picture of the life at Ellensbrook started to emerge.

“The traditional picture of life at the Missions is one of helplessness, but here we see clear evidence of human agency in resisting the efforts to control and shape these children’s lives.”

“As archaeologists, we use historical documents as a supplementary material to the material people leave behind,” says Sean.

“And so you go through the established history and then turn it sideways.”

(Un)sweeping generalisations

Sean also realised that they needed to tease out ‘accidental depositions’ from what people were purposefully putting under the floors.

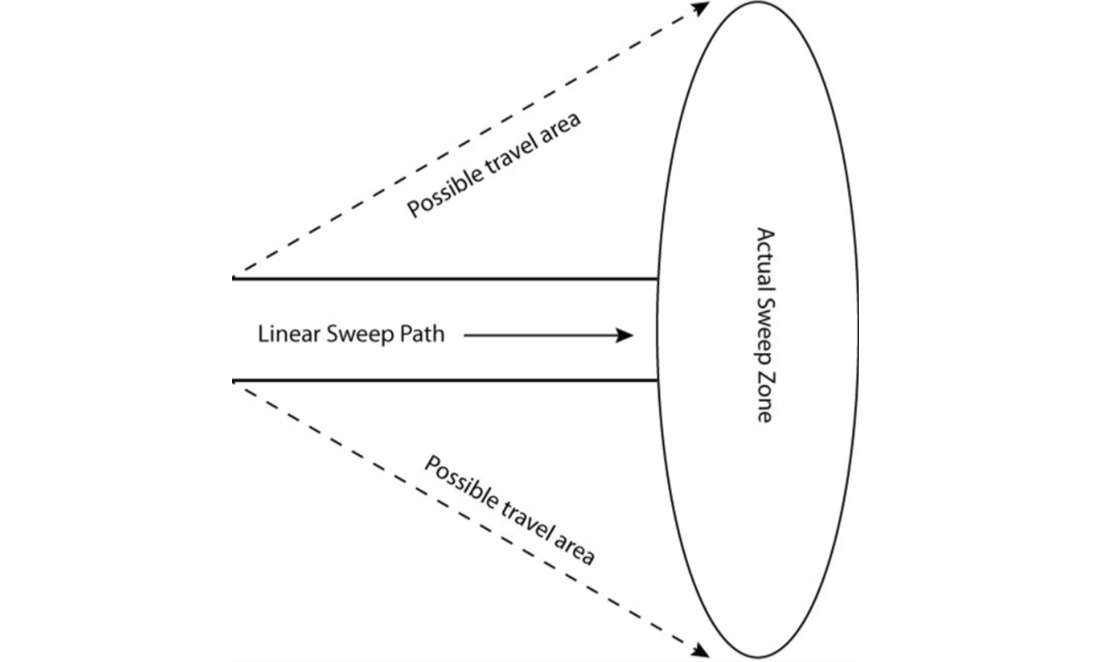

To further understand the forces at play, the team ran sweeping experiments on butt-boarded floors using hard-bristled broom brushes.

They saw how larger objects like shards of glass or ceramics often fell straight down when swept onto a vertical position. Gaps underneath skirting boards also allow larger items to skip straight through and fall into the underfloor space.

“We realised that we all had assumptions about how deposits developed underneath floor boards but without really understanding how it happened,” says Sean.

With all these new puzzle pieces coming to the surface, who knows what kind of details will be added to the history books?

It all builds up to a rich history – if you know where to look.