2015 Australian Emerging Architect Nic Brunsdon has well and truly emerged.

He has reinvigorated Perth’s glorious heritage buildings, educated architects of the future and launched an app. The professed urbanist and humanist (and 40under40 young business leader nominee) has certainly made an original impression on the field of architecture.

Particle spoke to Nic about the architectural overlapping of art and science, the psychological need for nice spaces and the importance of iteration in solving real-world problems.

Nic says …

Architecture is sort of like the perfect intersection between art and science. It’s this esoteric, emotional, responsive art—but you get there through science. You have to build in the physical world with materials and gravity and all those constraints. It’s where the fun of it lies.

You didn’t always want to be an architect. Growing up, you considered pursuing physics. What was the appeal?

It’s just one of those things I was always interested in as a kid.

Even today, I was invited back to my old school to give a talk, and I just spent the whole time talking about the bigness of time, the origins of the universe and putting yourself on that timeline—realising how fleeting and intractable it all is and why it’s precious and special.

Your default state as a collection of chemicals, it’s not you. You’ve spent 13.8 billion years as star dust, and then we’ve come together for these 82 years as you. So on that timeline, you spend a lot longer being not you. So, cherish the ‘you’.

“I think you can’t get into science or physics without also becoming a philosopher as well. You can’t look at those things and not just ponder everything.”

The work you do now, how does that incorporate art and science?

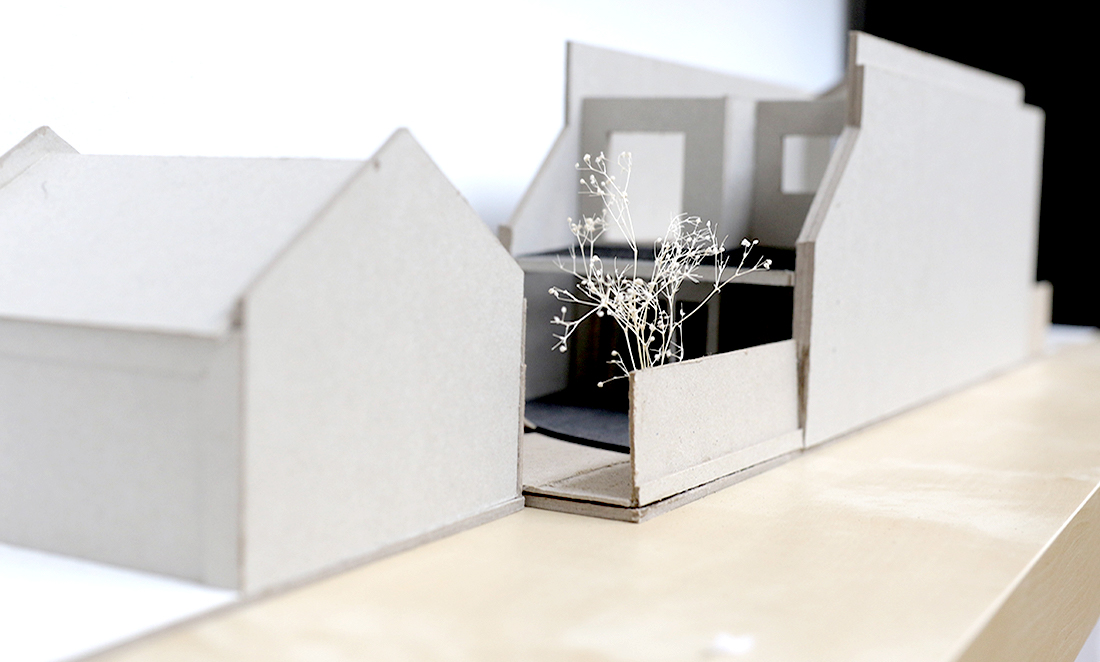

I think architecture is the nexus of those two things. It’s the art of living. It’s the most base human need—shelter—and that’s where architecture stems from, providing shelter and providing habitation.

As humans, we need places to inhabit, and there are different modes of that. There are residential homes, the private family unit, the open public space and the private work space.

Architecture to me is the art of putting science around those distinct modes. It’s about enhancing quality of life through science but in kind of intangible ways.

A lot of people walk in here and just go “Wow, what a great space”, but once you rationally go through it—there are high ceilings, there’s airflow, there’s natural light, natural material, it feels open and welcoming—when you turn off your responsive, primitive, reactionary mind and put on your logical mind, you know it’s because of those things.

In a world plagued with problems, why do people need architecture?

For mental health—it’s purely mental health.

A great space changes your life. It’s the art of living well.

You intuitively know when you’re in a great space. You automatically feel uplifted.

You also know what it’s like if you’re trapped in a horrible little cubicle or in a share house where you feel you don’t have privacy or you can’t engage and socialise properly. If those things aren’t made available to you, it just snowballs …

It’s one of those things we all know but don’t talk about. I guess because the world has turned a bit ‘stern parent-y’. Like it’s saying, “No, think about these things first, blah, blah, blah”, or “Don’t do that, that’s an indulgence”.

Good design doesn’t have to cost more. It’s just seen as being a luxury when it actually is a base human need.

Repetition is fundamental to the scientific process. How important is it for design?

Like the most important. You’ve got to keep testing until you prove something, keep failing until you get it right.

It’s something that we’re struggling with with clients at the moment. In architecture, we work in a field that is very logic and process driven, because a lot of the time the leaders of our industry are economists, procurement officers, project managers, and they live in the world of deadlines, deliverables and neat little packages. And the actual design process is much messier than that.

There’s something really great about having a strong, clear rational process, because it keeps you on track and it keeps you clear about where the project is heading, but there’s also something beautiful about risky, grey messiness because that’s where the unexpected happens. That’s where great mental-professional leaps happen, that’s where new things are found.

If you don’t get risky, if you don’t dip your toe in that pond, then nothing ever changes.

Where does inspiration come from?

I’ve got no ego about where ideas come from or the idea of authorship. I think there’s this myth of ‘The Personality’, the figurehead, and that everyone thinks that greatness or inspiration is a singular pursuit.

In fact, if you look at Nobel Prize winners or great works of architecture or music, you know there are always teams of people in ever-expanding circles around them.

“Think about what goes into making Beyoncé happen.”

For me, it’s kind of about killing the notion of singular authorship and understanding that there’s hidden untapped talent everywhere—that everyone is good. It’s just about providing the environment and the circumstance for those little moments to happen, for things to be dragged in the direction you weren’t expecting. To be open to allowing that to happen.

I remember someone saying something that I loved. It’s the concept of ‘strong ideas, loosely held’. So have a position, defend it, believe it, but as soon as you’re challenged with something that is better or that tears it down a bit, be willing just to let it go and move on.

Strong ideas, loosely held.

aRT AND SCIENCE HAVE LONG BEEN CONSIDERED TWO SEPARATE AND VERY DIFFERENT WORLDS.

In architecture, they come together to create solutions to real-world problems- both psychological and physical. But when we consider the iterative processes that are fundamental to both disciplines, we are forced to ask, were they really that separate to begin with?