Have you ever heard the expression “as blind as a bat”? Well, it’s not true. Bats can actually see as well or even better than humans.

In the dead of the night, however, eyes are of little use. Yet some bats go out every night and hunt for insects. They rely on the echoes made by sounds that bounce from their insect prey. In the brain of these bats, the echoes form a spatial representation of where the insect is flying about.

This ability is called echolocation, and it is well known in bats, toothed whales, dolphins and some species of birds and shrews. It allows them to find prey or learn about their environment when eyes are not so useful.

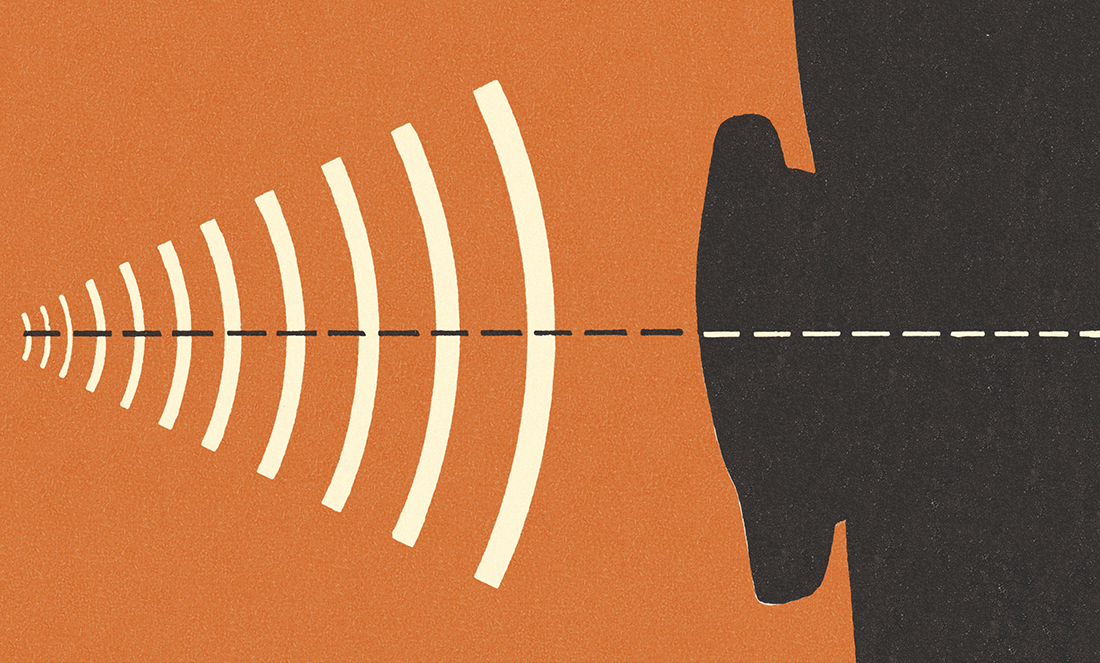

It works like this. A bat sends a sound wave, and when the wave runs into an object, it bounces back to the sender. The longer this echo takes to reach the sender, the further away the object. Once the echo reaches the bat, the animal’s brain is able to decode it into useful information, such as the shape of the object and how far away it is.

But did you know that humans, too, are capable of using echolocation? “Even children can learn by themselves to echolocate”, says Lore Thaler, a Professor of Psychology at the University of Durham in the UK.

The science behind being bat-men

Much like dolphins or bats, a human echolocator generates sharp clicking sounds with their tongue. “They are made by pressing the tongue against the soft palate [roof of the mouth] and then quickly pulling the tongue down. This creates a vacuum. This vacuum then ‘pops’, and this creates the ’click’ sound,” says Lore.

This sound will bounce back from any object it encounters as an echo, carrying information about the object it encountered, just like with bats. Depending on your echolocation skills, this echo can provide different information about the object.

“Recent research has shown that echolocation can provide rather a lot of detail about silent objects, such as their shape, size, distance and the material they are made of,” says Andrew Kolarik, a researcher at the Vision and Eye Research Unit, Postgraduate Medical Institute of Anglia Ruskin University, UK.

Seeing with sound

But what can you actually ‘see’? According to Andrew, an expert echolocator is actually able to get some sort of visual representation of the world. “A very rough visual analogy would be as if seeing the world through a blurry filter or through thick fog, where you can see the objects but it is hard to clearly make out the fine detail and the edges, and the visibility is just down to a short distance,” he says.

However, Lore warns not to get your expectations too high. We won’t be able to see the world with sound like with our eyes.

“You are working with sound, which is just fundamentally different from vision. Take glass as an example. Visually, you can see through it, it is perfectly transparent, but for echolocation, it might as well be a solid wall. Alternatively, a fleece blanket is invisible to echolocation, but obviously you can see it,” Lore says.

In a recent study, Lore found even further details about the inner workings of human echolocation.

We know bats and other animals adjust the sounds they make when their environment changes. But so far, it is unknown if humans can do this too. In her new study, Lore tested that very question and found that, indeed, people can adjust the sounds they make to better fit their environment.

“Another new finding is that we also measured the echoes that people could perceive. And we found that the echoes that the expert echolocators could perceive were very faint. Indeed, based on previous research, people would have said that it should have been impossible for them to perceive these echoes. But obviously, our echolocators were well up to the task!” Lore says.

Can anyone learn echolocation?

The good news is that anyone can learn this ability, blind or sighted.

Lore says that echolocation requires probably as much commitment as developing expert long cane skills.

Lore acknowledges that, while there are many people who have some basic echolocating skills, there are only a few who really master this ability. “I do not know how many people use click-based echolocation at very high skill level, but I am personally acquainted with 14. This is from all over the world.”

Why so few people? Lore thinks it is due to a lack of knowledge about this ability. “For example, blind people may not know about echolocation so just do not consider it. Or when a blind child or adult uses it spontaneously, they might be discouraged by well meaning sighted people because the sighted folks have no clue and they think it is odd,” she says.

Can echolocation replace the long cane or guide dog?

Not quite. Even for expert users who are blind, echolocation doesn’t provide all the information they need to walk about. Blind people, for example, never rely exclusively on echolocation, Lore explains. They use echolocation along with a cane or a guide dog.

“The benefit of echolocation is not to detect obstacles on the ground or holes or drops. In fact, for that purpose, it is quite useless because the ground itself is one giant reflector. Echolocation is useful for things at head level, to detect targets that are far away and to orient oneself.”

A bat-brain?

There is also a lot of variability in the capacity of learning this ability, and it is not clear what is driving this variability. “One of the issues in current echolocation research is finding out why some people are better at echolocating than others, whether they use a better strategy to hear changes in loudness or sound quality from echoes, for example, or how they develop enhanced sensitivity to sound echoes,” says Andrew.

But expert echolocators seem to have developed some special abilities at the level of their brains. “There is evidence that brain areas that process vision in sighted people become recruited to process sound instead for blind people, and this might contribute to the enhanced echolocation abilities that have been reported for some blind people,” says Andrew.