Imagine it’s May 1829. The British ship Parmelia is grounded on a sandbank near Garden Island, off the coast of what will soon become the Swan River Colony.

Aboard, Lieutenant Governor James Stirling sits with a young lieutenant, John Septimus Roe, in a cramped cabin. Together, Stirling writes and hands Roe a letter, officially appointing him the colony’s first Surveyor-General.

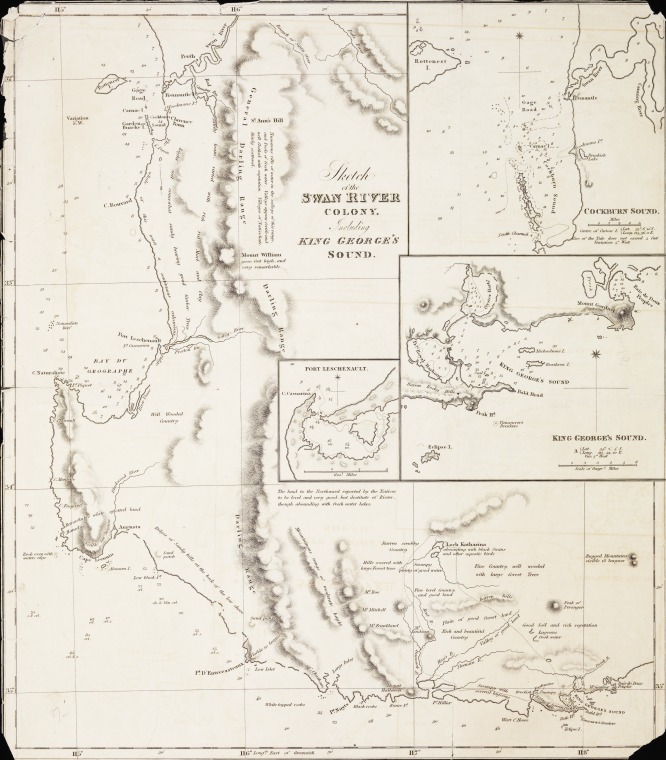

Roe’s job is to map a land that is vast and brimming with potential.

Supplied: WA State Archive

STEM on the frontier

In 2025, land surveying is relatively easy. In 1829, it was exhausting, dangerous and highly technical work. Surveyors like Roe relied on tools such as the theodolite to measure angles, chains to measure distances and the stars for celestial navigation.

WA is huge, with sandy ground, dense bushland and a harsh climate. With non-existent GPS, this was no walk in the park.

Roe and his team had to carry their equipment through swamps, climb rocky outcrops and endure blistering heat, all while sketching out the first maps of WA. It was science in the wild – unpolished but essential.

Surveying the uncharted land of WA required a blend of technical precision and sheer physical endurance. Roe relied on a suite of instruments that were simple by today’s standards yet innovative for the 1820s.

The theodolite, a device for measuring horizontal and vertical angles, was central to his work, allowing him to triangulate positions with remarkable accuracy.

To measure distances, his team used surveying chains – each 66 feet long – meticulously stretched across rugged terrain.

Navigation often relied on celestial observations, with Roe using a sextant and the stars to calculate latitude and longitude. Every measurement was recorded in detailed field books, which were later used to draft maps by hand.

The process was painstakingly slow and required extraordinary skill. Errors in measurement or misjudgements in navigation could cause significant inaccuracies on the final maps.

Despite the primitive tools and harsh conditions, Roe’s work laid down a blueprint for WA’s early settlements and infrastructure, showcasing the critical role of STEM in the most challenging frontiers.

Supplied: WA State Archive

Roe wasn’t just the guy with the map – he was the architect of early WA. His surveys laid the groundwork, literally, for towns like Perth and Fremantle. He marked out roads and property boundaries.

He documented the natural environment in intricate detail, noting soil types, vegetation and water sources. His records weren’t just for settlers looking to farm – they were for anyone trying to understand this awe-inspiring land.

A legacy with two sides

While Roe’s work was groundbreaking, it didn’t occur in an empty land. For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal people had called this place home, living in deep harmony with its ecosystems.

Their cultural and spiritual connection to the land was something European settlers, including Roe, largely overlooked.

When Roe mapped the Swan River Colony, he didn’t chart empty wilderness, he carved up occupied land that had been cared for and nurtured by Aboriginal communities for countless generations.

Fences were built, water sources were diverted and sacred sites were destroyed. Colonisation wasn’t just a physical act – it disrupted entire ways of life.

It’s a sobering reminder that history isn’t black and white. Roe’s achievements were significant, but they came at a cost that continues to affect Aboriginal communities to this day.

Supplied: WA State Archive

Balancing progress and reflection

How do we view someone like John Septimus Roe in 2025?

On one hand, his work laid the foundation for WA’s development. Without him, towns, roads and farms may have taken decades longer to be established.

On the other, his maps symbolise a time when progress came at the expense of people who had lived here for millennia, whose lives and families were forever altered in the name of colonial expansion.

The answer is balance. We can celebrate Roe’s ingenuity and grit without ignoring the impact of European settlement on Aboriginal communities.

Progress is complicated. It’s messy. Understanding it requires us to look at the bigger picture: the triumphs and the tragedies.

The next time you wander through Perth’s streets or drive across the sprawling WA landscape, think of Roe. Ponder the stars he used to guide his way, the chains he dragged through the bush and the maps he sketched on paper that would shape a city.

We must also consider the Aboriginal people, whose connection to the land runs far deeper than any surveyor’s chain. Think of the Aboriginal people whose land was carved up. Think of the Aboriginal people whose homeland was changed irrevocably.

Roe’s story isn’t just about maps and land. It’s about the meeting of two worlds – one of innovation and one of tradition – and the lessons we are still learning from both.