“If you’re born early, it interrupts every single cell and organ in your body,” says Denby Evans, a PhD student at Curtin University.

“[There are] so many different things that can be happening, it’s such a big puzzle to try and put together.”

“I really love trying to figure out what that mystery is and how we can help some of our teeny tiny babies grow up big and strong.”

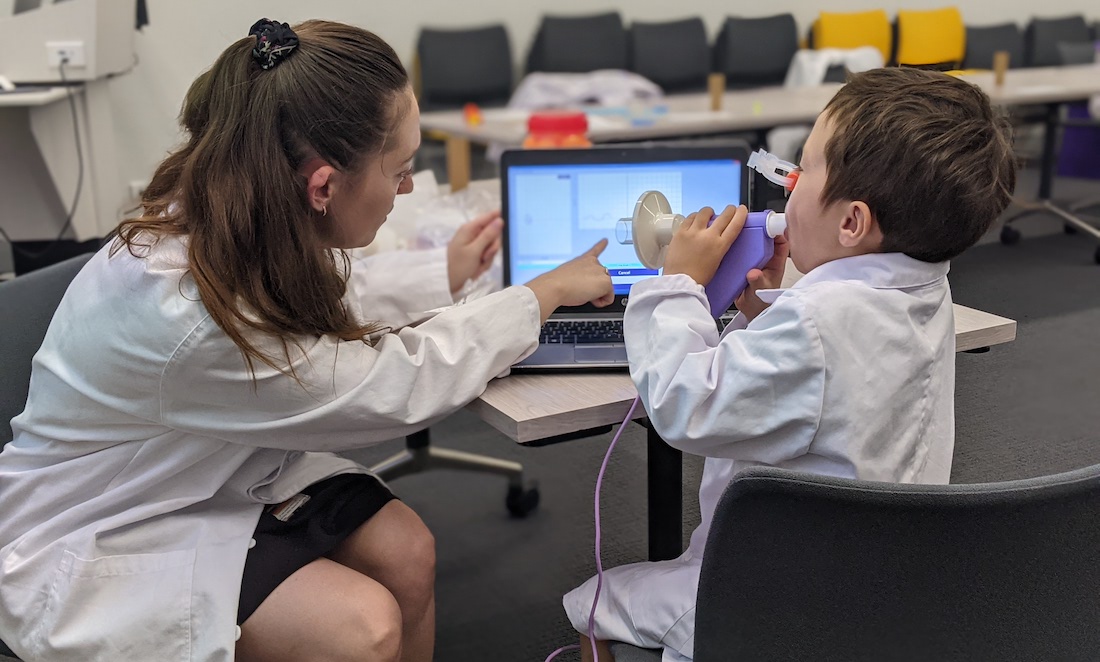

Denby was recently named Student Scientist of the Year at the 2023 WA Premier’s Science Awards for her contributions to improving the lung health of premature babies.

In addition to her studies at Curtin, Denby is actively involved in research at the Wal-yan Respiratory Research Centre – a partnership between the Telethon Kids Institute, Perth Children’s Hospital and Perth Children’s Hospital Foundation.

The centre’s name comes from the Noongar words ‘wal-yan’, meaning lungs, and ‘war-lang up’, meaning healthy place, to form ‘place of healthy lungs’.

WE BELUNG TOGETHER

Globally, about one in 10 babies are born preterm (before 37 weeks). In WA, that’s about 3,000 babies a year.

Due to the interruption in their lung development, these children can cough, wheeze or have trouble running around with their friends.

However, for children born very preterm (before 32 weeks) their lung health continues to get worse rather than better during childhood.

“What we really want to do is try and understand what it is that’s causing that lung function to get worse,” says Denby.

“Once we understand what’s causing it, then we can start trying to find treatments to help improve that.”

THE SILENT EMERGENCY

It’s unknown what causes breathing problems in kids born preterm. So experts cannot yet predict who will be affected.

“A lot of the things they’re exposed to in the neonatal intensive care unit – how much oxygen they get, whether they’re diagnosed with chronic lung disease as a baby – doesn’t necessarily translate into whether they’re going to have breathing problems as a child,” says Denby.

“So we’re really trying to dig deep … and figure out what it is.”

During her research, Denby discovered that airway cells behave differently in children born preterm, even months or years after birth.

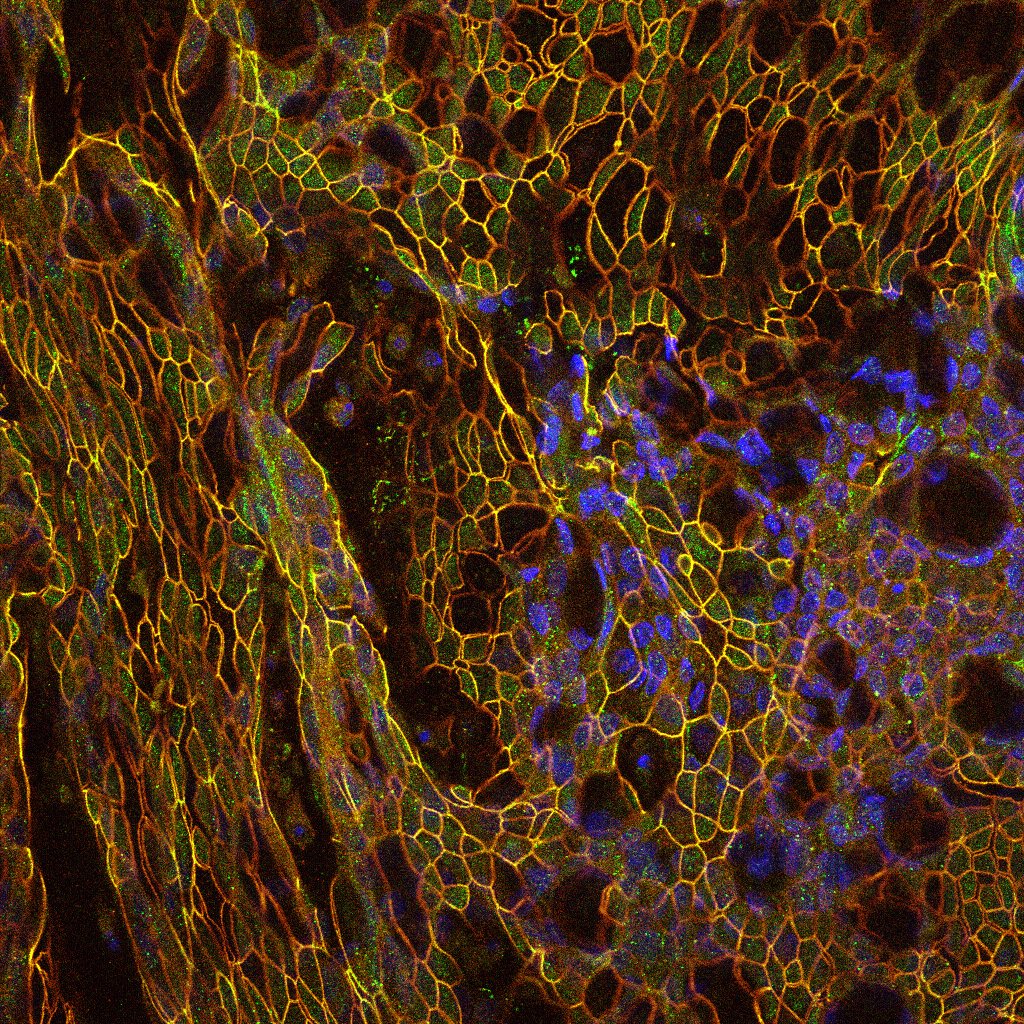

And the difference can be seen under a microscope.

“We’ve actually been staining them for the proteins that hold the cells together, which are called ‘tight junctions’.” says Denby.

“They don’t join as tightly – you can see the gaps between the cells.”

These airway cells are the first line of defence against viruses and bacteria that can make us sick.

“When the cells aren’t joining together as tightly, it’s actually letting a lot more of the nasty bugs get through, which is going to make these kids get more colds and coughs,” says Denby.

“And we already know that they do. We see that clinically.”

HOPE FOR THE FUTURE

Children born preterm are often prescribed asthma medications such as inhaled corticosteroids.

But research from the Wal-yan Respiratory Research Centre suggests these only work for about 25% of children.

Denby is currently testing new drugs on airway cells in the lab, hoping to find a better treatment.

“We’re [trying] … to understand what the disease is … what we can use to treat it, and then hopefully translate that into the clinic,” says Denby.