Virus outbreaks are becoming more frequent and spreading faster as our world becomes increasingly globalised.

Since 2000, the number of airline flights per year has doubled and our global population has increased by 33%.

This increased globalisation means infectious diseases can spread more easily.

Some of these infections are ‘emerging’, meaning they are new or have recently become persistent and uncontrollable.

We have a long history of battling infectious diseases with vaccines and sanitation.

From eradicating smallpox to eradicating diseases like yellow fever and polio from many countries, it poses an important question.

Can immunisation or other interventions ever eliminate these threats entirely?

RECENT INFECTIONS

Infectious diseases are illnesses caused by the transmission of viruses, bacteria, fungi or parasites from humans, animals or environmental sources such as food and water.

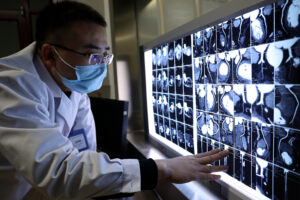

Caption: T cells are a type of white blood cell that help your immune system fight germs and protect you from disease

Credit: cgtoolbox via iStockphoto

The emergence of COVID-19 in 2020 brought the world to a halt. It was our fifth recorded pandemic.

The World Health Organization (WHO) official COVID-19 death toll is over 7 million people. It’s estimated the actual death toll is over three times higher.

Bird flu also surged in 2020 with a particularly pathogenic variant called H5N1. It quickly spread around the globe, including to Antarctica.

Bird flu symptoms in humans range from none to mild flu-like symptoms to severe cases requiring hospitalisation.

In 2022, mpox (previously called monkeypox) reappeared. The WHO quickly declared a public health emergency. While mpox has a low mortality rate, the virus spreads rapidly and causes many hospitalisations.

In the past 5 years, there have been three major global incidences of infectious disease. Can we mitigate them and any new infectious diseases?

ERADICATION STATIONS

Hannah Moore is the Head of Infectious Disease Research at The Kids Research Institute.

“Vaccines are critical in reducing the severity of the impact of disease,” says Hannah.

“The goal is not necessarily to eliminate all infections but to aim to significantly reduce deaths and hospitalisations.”

An infectious disease must meet three criteria to be eradicated.

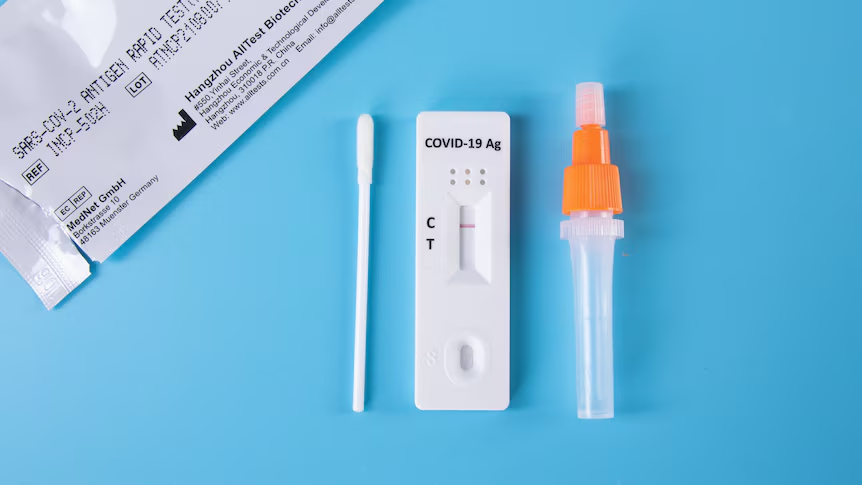

First, the disease is easily detectable through identifying physical symptoms or diagnostic testing.

Credit: Jernej Furman via Flickr

Second, the disease must not be able to infect multiple species. Dengue fever spreads through mosquitoes, making it easy to transfer to non-human species.

Finally, there must be a means of limiting the spread of disease. Commonly, this is a vaccine but not in the case of cholera, which was eliminated in certain areas by improving sanitation.

The global incidence of infectious disease is still increasing. Experts are concerned we are not ready for the next outbreak.

ARE WE READY?

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in global preparedness and response systems.

Five years on, experts believe we are still “grossly unprepared” for the next pandemic. Hannah echoes this sentiment.

“The declining rates of immunisation we are experiencing together with increased global travel and urbanisation, emerging and re-emerging viral infections pose a larger risk than in previous years,” says Hannah.

“Next time around, the public is likely to be less receptive to public health measures like lockdowns … If people aren’t willing to follow these measures, they won’t be nearly as effective.”

Credit: Edward Jenner via Pexels

Hannah has some suggestions to prepare for future outbreaks.

“We need targeted investment in surveillance, particularly for diseases that can infect multiple species, to enable early detection,” says Hannah.

“A coordinated approach is essential across all levels of government, with expert input and consistent vaccine policies spanning the entire healthcare system.”

While we may be unprepared for the next pandemic, we know what to expect and are aware of imminent threats.

In the meantime, vaccines save lives and eliminate infectious disease where possible.